It’s finally here!

This is the time of year when bosses, friends, and spouses may wonder if they’ll ever see the birder in their lives again. Yes, it’s spring migration time, and we’re all up and out the door before dawn to bird until the sun sets. Of course, we continue to stand in open fields after the sun sets waiting to hear woodcocks and rails.

Some of us (names are withheld to protect the guilty) may even call off work the morning after a night of strong southwest winds. Those winds bring migrants, you know.

The birding news from across North America is at its typical spring peak of hysteria. If there’s one phrase to sum up the migration so far it would be phenological anomalies. Phenology is the study of the timing of life cycle events of plants and animals. (This should not be confused with phrenology, which is the belief that a person’s personality and character can be determined by taking measurements of his or her skull.)

Since most of these organisms rely on weather and climate for cues to their behavior, an absurdly warm March can bring about some highly unusual changes in timing, i.e. phenological anomalies. And in the Midwest and much of the Northeast, March was nothing if not absurd from a weather standpoint. Spots in Michigan were breaking record high temperatures for several days in a row, sometimes by more than 10 degrees Fahrenheit.

Has This Year's Odd Behavior Affected The Migration?

What has all that unseasonable weather meant for bird migration, particularly in some national parks where spring migration is a noted annual spectacle?

One of the first Field sparrows in Michigan this year. Kirby Adams photo.

Let’s look at Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore and see what’s been happening. Field Sparrows (Spizella pusilla) are one of my favorite songbirds. They’re very sharp looking sparrows with a bright pink bill and striking pattern. Their song is always a highlight of the warm days of mid to late April in the Great Lakes region. I liken it to a bouncing ball, starting off with a few strong notes and trailing off to an increasingly rapid trill of weakening notes. Others compare the song to water going down a drain.

At any rate, it’s a song that was heard at Indiana Dunes on March 11th this year, three to four weeks earlier than usual. Likewise with another pleasant spring singer, the Eastern Towhee (Pipilo erythrophthalmus), which made an appearance on the Lake Michigan shore on March 15th, compared to a usual arrival in mid-April.

Early arrivals are exciting for a birder, especially when you get to be the first in your area (or state!) to report a bird for the season. But these anomalies can be devastating to birds and other species if they become a trend. If the birds arrive and begin nesting a month early, they may need to find a different insect to eat to meet the energy demands of brooding if their usual meals aren’t flying around yet. Even if the birds manage to do this, the insects that hatch later may have less predation pressure and become more likely to devastate certain plant communities, which in turn puts pressure on whatever animal eats those plants – possibly another bird.

If anyone doubts the old adage from John Muir that when one tugs at any one thing in nature he finds it hitched to everything else, these phenological anomalies will drive the point home. The importance of recording and tracking these anomalies is all the more reason for birders to become active citizen scientists, reporting first sightings to places like eBird.

Buff-breasted sandpipers migrate from South America to the far north every spring. Kirby Adams photo.

The more ornithologists can learn about timing of migration, the more they can predict the habitat and conservation needs of the birds.

Showing Up Ahead Of Schedule

While early arrivals are lighting up birding list-servs in the Midwest and Northeast, down at Padre Island National Lakeshore an American Golden Plover (Pluvialis dominica) showed up on April 5th, which is right on time compared to other years that this master of long-distance migration has passed through Texas’ Gulf Coast. A lucky observer up in Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore could hope to see one around May 15th, give or take a week, regardless of weather.

So, when the first Dark-eyed Juncos (Junco hymalis) are appearing near Pictured Rocks a month early this year, and the Towhees and Field Sparrows are equally early at Indiana Dunes, what’s the deal with the always-punctual Golden Plover?

To answer that question, we need to know where these birds have spent their winter. The three sparrows we’ve mentioned (Towhees and Juncos are types of sparrows) all winter in the southeastern United States. You could find any of them on a January excursion along the Buffalo National River in Arkansas, for example.

The American Golden Plovers are returning from a “winter” where it was actually summer, the southern portions of South America. For a bird like this plover that makes a 25,000-mile round-trip annual migration, the cues to migrate can be different than those for the birds that are merely shifting a couple hundred miles north.

Circannual rhythms of hormone production and changes in the length of day are the dominant factors stimulating the long-distance fliers to take off. While those are also important in migration of short-distance migrants, weather can override some of those cues and prompt an early move.

An abundance of a preferred insect or vegetable food, triggered by an exceptionally warm late winter, are all it can take to get a Towhee flying north a month early. Thus, while March and April have seen numerous “first arrival” records broken this year, the pace will return to normal now as we await the migrants that spent the winter months in the tropics or the southern hemisphere.

Bringing Color Back To The Parks

Speaking of tropical migrants, many of the brightly colored warblers that make birders go bananas in the spring are in that category.

Prothonotary warbler, a favorite among warbler watchers in the east and south. Kirby Adams photo.

Warblers like the Blackburnian, Bay-breasted, and Chestnut-sided are all favorites of the May crowds of birders at Cuyahoga Valley National Park, and summer birders at Pictured Rocks. These birds are on their way back from Central and South America, and will either be crossing the Gulf of Mexico or going around it very soon. Migration stops like Padre Island, Gulf Islands National Seashore, and Dry Tortugas National Park are the places to be for warbler watching over the next two to four weeks.

How will you know when they’re coming? One good method is to follow the weather reports. Birds crossing the Gulf of Mexico will wait for favorable winds. If there’s a sudden storm or change of winds along the Gulf, a birder could even be treated to a “fallout.”

Fallouts are legendary events in the birding world. Minor ones happen all the time when a storm system forces flocks of migrants to stop their flight and settle wherever they are. Occasionally, however, a fallout of epic proportions will occur when warblers, vireos, and tanagers are literally raining from the sky.

While exciting for a birder, these are trying events for the birds. Already weak from a migration flight, fallout birds often find themselves in inappropriate habitat to find both shelter for immediate protection and fuel to continue their migration.

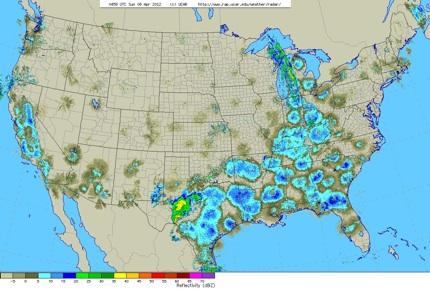

Another tool for predicting migration is at the disposal of the modern birder as well: weather radar. Yes, the flocks of migrating birds are big enough and dense enough this time of year to show up as well as rain does on Doppler radar.

Some ornithological labs and bird watching websites are now dedicated to radar tracking of bird migration. You have to wonder what John James Audubon would think about that!

I hope everyone gets out to enjoy spring migration in our beautiful National Parks this season. Don’t forget to check for park programs like those we mentioned in Cuyahoga Valley National Park or birding and nature festivals as we discussed during the winter.

Spring migration only comes around once a year. Don’t miss it!

Comments

Kirby,

Great article! You're right- the cascading effects of this anomalous warm spring are being felt across the country, and eBird is really helping us quantify the results like never before. There is also a growing network of bloggers posting daily (or almost so) radar animations, weather maps, and their own interpretations related to nocturnal bird migration across the country. I run a site (thanks for the link above!) that focuses on the Upper Midwest and the Mid-Atlantic regions (http://www.woodcreeper.com), but your readers may also be interested in knowing about the sites covering other regions of the country:

The Pacific Northwest (http://birdsoverportland.wordpress.com/)

New England (http://tomauer.com/blog)

Pennsylvania and the Ohio Valley (http://www.nemesisbird.com/)

Florida and the Caribbean (http://badbirdz2.wordpress.com/)

and as you mentioned eBird in your article, the eBird team is posting weekly migration forecasts on the eBird homepage. Here is the latest migration forecast for this week: http://ebird.org/content/ebird/news/bcf20120406

Thanks again for the great article.

Thanks, David. This is definitely not your grandfather's spring migration - with radar, blogs, eBird data updated right from the field via smartphone, etc. Some of the purists may argue this, but I think this is a thrilling time to be a birder. (I'm speaking of the 21st century, not just April and May!)

Also, I meant to point out, but forgot, that the sighting dates mentioned in the article are based on eBird and my personal monitoring of blogs and list-servs. There may be some additional data buried in state birding records for the past, but it's safe to say this March was quite an anomaly.