Editor's note: The following is the first half of an article on the significance of religious symbolism at the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial in Indiana, symbolism that the National Park Service has largely overlooked. The author, Richard Sellars, was a historian for the National Park Service for three decades. He is the author of Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History (Yale University Press, 1997, 2009). This book inspired the Natural Resource Challenge, a multi-year initiative by Congress to revitalize the Park Service's natural resource and science programs.

On a calm, sunny day in mid-October 1985, I made my first visit to the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial in southwestern Indiana, where Abraham Lincoln lived for fourteen years as he grew into manhood. The National Park Service has overseen this site since the early 1960s.

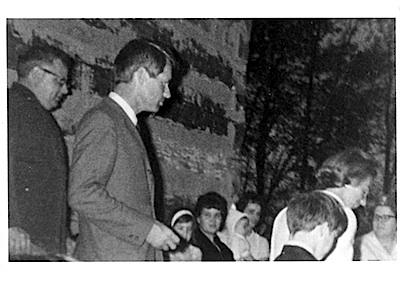

Three times as I walked around the memorial grounds, two elderly women probably in their mid-eighties quietly approached me. One of them had a photograph in her hand, and at each encounter she showed it to me'a black-and-white snapshot of Senator Robert F. Kennedy, taken during his visit to the boyhood memorial while campaigning for the presidency in April 1968. Standing near a log cabin, he was facing a small gathering of people probably from the surrounding rural area. Kennedy was, she told me, 'just a simple country boy at heart.'

The old woman's message seemed focused on death and loss; and in her fragile yet determined way there were hints of tragedy that befell the men involved. I later learned that her husband had helped transport the log cabin from its earlier location to the boyhood home site to be the centerpiece of a Lincoln farm exhibit; and he had assisted with Senator Kennedy's visit. Her husband had since died. And of course Kennedy was assassinated in June of 1968, and JFK before him, and Lincoln long before that. All the sons and husbands and fathers were dead'and years later, this frail old woman was obsessed simply by Robert Kennedy having been there, on the Indiana farm where Lincoln once lived.1

U.S. Sen. Robert Kennedy visited the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial in 1968, shortly before he was assassinated.

The boyhood memorial is an important national tribute to Lincoln. And had Senator Kennedy, a devout Catholic, been shown the memorial's several prominent religious symbols, surely he would have found their expression of great reverential respect for Lincoln more meaningful than a substitute log cabin that had had no contact with the Lincoln family. But the National Park Service has shown little interest in the park's religious symbols'it prefers the cabin.

* * *

Historian David Donald, in looking back nearly a century after Lincoln's death, observed that 'the Lincoln of folklore is more significant than the Lincoln of actuality' because the Lincoln of folklore 'has become the central symbol in American democratic thought; he embodies what ordinary, inarticulate Americans have cherished as ideals.' 2 Indeed, Abraham Lincoln's pathway from backwoods obscurity to the White House is marked by an array of preserved and protected historic places that attest to his veneration and his stature as the mythical personification of the nation's democratic ideal'the reigning figure in American civil religion.

Several of the most prominent Lincoln sites, such as his home in Springfield, Illinois, Ford's Theatre in Washington, and across the street the Petersen House where he died, portray aspects of the historic Lincoln, the gifted mortal'husband, father, lawyer, president. Other places are more clearly shrines: The imposing neoclassical marble temples found at the Lincoln birthplace in Kentucky and the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., reflect his deification in the public mind.

In Indiana, the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial also suggests his deification, but in a distinctive way. Reflecting a devoted public's high tribute to Lincoln and his mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, the memorial's designers rejected neoclassicism and chose traditional Christian symbols.3

On my first visit to the Lincoln boyhood memorial, I realized how exceptional this park is with its formal commemorative features that associate Lincoln with Christianity. It also differs from major sites outside the National Park System that honor Lincoln, including his cottage at the Soldiers' Home (a summer retreat a few miles north of the White House), and, in Springfield Illinois' Oak Ridge Cemetery, the elaborate Lincoln Tomb, which is devoid of Christian imagery.

The Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial may indeed have more Christian features than any other site in the National Park System set aside to commemorate purely secular history. Completed in the mid-1940s, these features include a landscape designed in the shape of a huge cross, a bas-relief limestone sculpture of Lincoln's apotheosis, a 'Trail of Twelve Stones,' a cloister, and attached to it, a chapel. My interest in the park's Christian aspects arose not from any religious convictions, but from concern about how and why the National Park Service has obscured the deification of Lincoln in this park dedicated to honoring his memory.

The boyhood memorial's Christian connection is puzzling, given Lincoln's unorthodox religious views. As noted by Lincoln scholar Douglas L. Wilson in Lincoln's Sword: The Presidency and the Power of Words, the president's widow, Mary Lincoln, recalled in an 1866 interview that her husband had been religious, but had 'no hope & no faith in the usual acceptation of those words: he never joined a Church.' She added that he was not a 'technical Christian.' With the loss of their son, Willie, in February 1862, then with the intensification of the war and Lincoln's trip to Gettysburg, Mary had detected a rise in his religious feelings. But it seems clear that he was never truly devoted to Jesus. Yet he had a thorough knowledge of the Bible and attended church services with Mary in both Springfield and Washington. Lincoln also acknowledged an Almighty presence in human affairs, most famously in his Gettysburg Address, and in the Old Testament-New Testament conclusion of his Second Inaugural Address.4

Just as puzzling, however, is the National Park Service's disregard for the boyhood memorial's Christian symbolism. Since taking over the site in the early 1960s, the Service seems never to have explained to the public the memorial's Christian features created to venerate Lincoln. It even avoids calling the chapel a chapel. Ignoring the symbolism does not appear to stem from concerns about Lincoln's personal religious views, nor from First Amendment church-and-state concerns'at least not that I could detect.

And if park rangers were to explain to visitors the Christian references and what they suggest about the public's great esteem for Abraham Lincoln, I see no reason why promoting religious dogma would play any part in this. The Park Service has successfully dealt with much more complex religious matters. For example, at San Antonio Missions National Historical Park, in Texas, the Service interprets the history and architecture of the park's main attractions'four 18th century Spanish missions, which played a principal role in the Spanish frontier movement. Although surrounded by park lands, the missions themselves remain active churches, owned, worshiped in, and cared for by the San Antonio Archdiocese.5

* * *

The Lincoln family sojourn in southwestern Indiana began in 1816, when they moved up from Kentucky. Abraham was only seven, and he would spend his most formative years there: helping his father clear the heavily forested land and work the farm; experiencing deep personal tragedies with the death of his mother and sister; and hiring on for a trip down the Mississippi River to New Orleans, where he encountered more slaves than he had ever before seen. He also educated himself to the extent possible given his circumstances. Encouraged by his mother and then his stepmother, Abraham developed an intense intellectual curiosity, becoming well-read and well-regarded in the rural neighborhood. The family departed for Illinois in early March 1830, less than a month after Lincoln turned 21.

In contrast to the significance of Ford's Theatre in American history, apparent soon after the fatal shot, the historical significance of the boyhood farm was not recognized until more than a third of a century after Lincoln left Indiana. This recognition came not so much when Lincoln was elected president, but after his death, when, on the roster of Civil War heroes and martyrs, Lincoln soared to the top, into the realm of Presidential Gods, and toward his mythical, folkloric status.

As viewed by three prominent Lincoln scholars in The Lincoln Image: Abraham Lincoln and the Popular Print, the martyred president's 'swift transcendence from history into folklore was one of the more remarkable cultural phenomena' in American history.6 Lincoln's rise in public esteem unquestionably extended into Indiana where it ultimately inspired the boyhood farm's commemorative phase. The farm site emerged from obscurity to attain historical status and, in time, to be adorned with Christian symbolism in high tribute to the mythic Lincoln.

But for many years after the assassination, public interest in the site focused on the memory of Nancy Hanks Lincoln, whose unmarked grave, mostly forgotten until after her son's death, began to attract local pilgrims'even though the grave had not been authenticated (nor has it since).7 The cult of motherhood, strong in this era, surely helped inspire admirers to place a permanent marker at the presumed grave in 1879. At the turn of the century, and with a sizeable contribution from Robert Todd Lincoln, the local county acquired the gravesite and nearby lands.

The site evolved into a shrine to which pilgrimages were made, usually on Mother's Day. In the 1920s, Indiana designated the area the Nancy Hanks Lincoln State Memorial, and charged the Indiana Lincoln Union with overseeing its development.8 Renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., oversaw the memorial's initial conceptual designs, and Indiana citizens, including thousands of children, contributed to a fund-raising campaign for development of the memorial.9 The Lincoln Union completed the commemorative Christian features by the mid-1940s.

Of all Lincoln sites, it is here in Indiana, where Lincoln's mother is buried and the memorial was established in her honor, that veneration of Nancy Hanks Lincoln reached its highest level. Reflecting its great adoration, the Indiana Lincoln Union used such reverential verbiage as the 'sainted Mother,' whose grave was 'sacred soil,' and to which 'pilgrimages' were made. Lincoln Union officials in their promotional literature also declared that the Union was 'memorializing democracy and religion,' and that the memorial park was a 'shrine to Motherhood and to the family hearthstone.' 10

Centered on the mother's gravesite in this rural Indiana countryside, and somewhat suggestive of the adoration of the Virgin Mary, the veneration of Nancy Hanks Lincoln, culminating with the memorial park, rivaled that of her martyred son'and the Lincoln Union's reverential verbiage was reflected in the use of Christian symbols. The symbols were put in place long after the Lincolns left the area, and by people who expressed their feelings through these Christian references, surely to many donors across Indiana the highest honor they could pay. 11

And yet the Lincoln Union's commemorative Christian features clearly shifted emphasis from the mother toward the son. The most striking evidence of this is the park's chief memorial structure, the cloister'the very name of which suggests cathedrals and quiet meditation. Built of native stone, the cloister originally consisted of a gently curving and roofed walkway with large arched openings at intervals along the walls, in the tradition of contemplative spaces in Christian architecture. Intended to honor both Lincoln and his mother, the cloister gives much greater tribute to Lincoln.

For instance, along the front facade of the cloister, a row of five large, sculpted, bas-relief limestone panels depicts different phases of Lincoln's life'the Kentucky, Indiana, Illinois, and Washington years. A central panel graphically portrays his apotheosis: a robed Lincoln ascending to the heavens'the emergence of a new American deity. Bearing a perfect Old Testament name for an American patriarch, Lincoln is, in effect, depicted in transition toward his mythical Father Abraham image.

Adding to the Christian aspects of the boyhood memorial, the semicircular cloister connects on one end with what was originally called the 'Abraham Lincoln Chapel,' complete with a pulpit, choir loft and cherry-wood pews. Church services were held there periodically, but have been discontinued, yet the chapel continues to accommodate weddings. (At the opposite end of the cloister, the Union built the Nancy Hanks Lincoln Hall, featuring a large, handsome fireplace and landscape painting, which, in honoring Lincoln's mother, give an idealized suggestion of home and the family hearthstone.) 10

Further binding Lincoln to Christianity, and adding to the emphasis on Abraham Lincoln instead of his mother, the Union developed another feature: the 'Trail of Twelve Stones''which evokes the Stations of the Cross, as found especially in Catholic places of worship, but also in some Protestant churches. Placed at intervals along the trail as it winds through the woods, the twelve stones, like those in churches that depict scenes along Jesus' way to his crucifixion, represent sites associated with Lincoln's pathway through life, ending with his martyrdom. Included are stones from his birthplace farm in Kentucky, his store in New Salem, Illinois, and the Petersen House in Washington where he died. Along the trail and interspersed with the stones (or 'shrines,' as the Lincoln Union referred to them at times) are recessed areas and benches to provide for quiet contemplation by 'pilgrims'. 12

Not far from the trail, the memorial park's designers developed an allee, a long, formal, rectangular grassy area lined with trees, which intersects at a right angle with a linear plaza to form the shape of a large cross. Albeit perhaps never readily apparent from ground level, the cruciform stands out plainly in the designers' drawings. 13

With the addition of these features associating Lincoln with Christianity, the grave of Nancy Hanks Lincoln remained one of the state memorial's important sites to visit'but no longer its foremost feature. Then, during the Civil War Centennial in the 1960s, and with the backing of Indiana officials, Congress authorized National Park Service oversight of the memorial. Congress also abandoned the Nancy Hanks Lincoln designation, renaming the site the Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial'making official the decreased concern for the mother, in favor of the son.

Tomorrow: The National Park Service develops a new philosophy for interpreting the site.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 RWS Journal, October 21 1985

2 David Donald, Lincoln Reconsidered: Essays on the Civil War Era (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1959), 164-165; quoted in Michael Kammen, Mystic Chords of Memory: The Transformation of Tradition in American Culture (New York: Vintage Books Edition, 1993), 128.

3 Rejecting neoclassicism: Marla McEnaney, 'A Noble Avenue: Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial: Cultural Landscape Report,' (National Park Service, 2001), 41-42; online at: http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/libo/noble_avenue_clr.pdf (accessed January 1, 2014).

4 On Lincoln and religion, see Douglas L. Wilson, Lincoln's Sword: The Presidency and the Power of Words (New York: Random House, 2006), 250-263; quotes, 251-252. See also Douglas L. Wilson, Honor's Voice: The Transformation of Abraham Lincoln (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998), 75-85; Ronald C. White, Jr., A. Lincoln: A Biography (New York: Random House, 2009), 35-36, 55, 135, 622-626; and David Herbert Donald, Lincoln (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), 33, 49, 74, 337, 566-567.

5 Information on San Antonio Missions from telephone conversations with Al Remley, chief of park interpretation, February 5, 2013; Art Gomez, former historian at the missions, February 17, 2014; and my own recollections from my involvement in planning the park (late 1970s-early 1980s), and a three-month tenure (spring 1988) as acting superintendent of the missions park. Very recent sources are: Greg Smith, 'Church and State: A unique partnership is at the core of the management of San Antonio Missions National Historical Park'; and Susan Snow, A Look Back', published together in Ranger: The Journal of the Association of National Park Rangers, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Spring 2014), 6-7. The most thorough study of religion and the national parks is found in Lynn Ross-Bryant, Pilgrimage to the National Parks: Religion and Nature in the United States (New York and London: Routledge, 2013). It focuses on the large natural parks.

6 Harold Holzer, Gabor S. Boritt, and Mark E. Neely, Jr., The Lincoln Image: Abraham Lincoln and the Popular Print (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1984), 149.

7 Information on unauthenticated burial site from Michael A. Capps, chief park historian and interpreter, on site, April 23, 2012.

8; Evolution of site commemoration is discussed in Marla McEnaney, 'A Noble Avenue,' 1-2, 8, 11-12; online at: http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/libo/noble_avenue_clr.pdf (accessed March 29, 2013); Jill York O'Bright, 'There I Grew Up'¦A History of the Administration of Abraham Lincoln's Boyhood Home' (typescript, National Park Service, 1987), online at: http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/libo/adhi/adhi1.htm , chapter 1 (no pagination), accessed March 15, 2013); and Michael A. Capps, 'Interpreting Lincoln'A Work in Progress: Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial as a Case Study," Indiana Magazine of History: Volume 105, Issue 4, pp: 327-329, online at http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/imh/view.do?docId=VAA4025-105-4-a03 (accessed March 29, 2012). The patriotic efforts to honor Indiana's most revered family were boosted by the need to restore credibility of the state government following overthrow of its short-lived and disgraced Ku Klux Klan leadership. See Keith A. Erekson, Everybody's History: Indiana's Lincoln Inquiry and the Quest to Reclaim a President's Past (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012),112-120, 132.

9 Development of the park included purchase and removal of the remains of a small village, and re-routing a highway. Jill M.York, 'Friendly Trees,' 2-7; O'Bright, 'There I Grew Up'¦A History of the Administration,' online at: http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/libo/adhi/adhi1.htm , chapter 1 (no pagination; accessed March 15, 2013). Children's contributions are noted in McEnaney, 'A Noble Avenue', 1; online at: http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/libo/noble_avenue_clr.pdf (accessed March 29, 2013); for the park's religious symbols, see text, photographs and captions in National Park Service: Abraham Lincoln: A Living Legacy, 58, 60, 62-64.

10 McEnaney, 'A Noble Avenue,' 12; online at: http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/libo/noble_avenue_clr.pdf.

11 For observations on the religious symbolism at Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial, I am indebted to Dr. Yvonne Lange (now deceased), former director of the Museum of International Folk Art, in Santa Fe, and an author and recognized expert on Christian iconography, with whom I discussed this topic on several occasions in the mid-1990s.

12 For direct reference to the passion of Jesus, see McEnaney, 'A Noble Avenue,' 40; and McEnaney, 21-22 for shrines and pilgrims; online at: http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/libo/noble_avenue_clr.pdf; accessed March 29, 2013); Capps, 'Interpreting Lincoln,' 332; online at http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/imh/view.do?docId=VAA4025-105-4-a03 (accessed March 29, 2013); Erekson, Everybody's History, 119.

13 Jill M. York, 'Friendly Trees,' 16, and cover illustration. McEnaney, 'A Noble Avenue', photos: 16, 18, 19, 31, and following pages 14, 24, online at: http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/libo/noble_avenue_clr.pdf (accessed April 4, 2013); See also Capps, 'Interpreting Lincoln,' 330; online at http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/imh/view.do?docId=VAA4025-105-4-a03 (accessed March 29, 2014).

Comments

This has to be one of the most interesting articles I've ever seen in Traveler. I'm looking forward to the next chapter.