The Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee is comprised by officials from two national parks, five national forests, the Bureau of Land Management, and two national wildlife refuges

This year marks a milestone in the management of the Greater Yellowstone Area. It starts the second 50 years of the Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee, created by the U.S. Forest Service and the National Park Service in 1964.

The GYCC mostly operates outside of the public view, but it sometimes attracts public attention, Indeed, it saw a moment of notoriety 25 years ago around its 'Vision' project. Though the technical nature of its work often obscures the politics behind the scenes, political controversies are as much a part of the Yellowstone National Park landscape as geysers and bison.

By creating the GYCC, NPS and the Forest Service recognized that many of their management challenges cross the boundaries of national forests and national parks. Bison migrate out of Yellowstone into Gallatin National Forest. Yellowstone shares its watersheds with its neighbors, with many rivers and streams entering the park from national forests before leaving the park ' perhaps into a different national forest. Research by John and Frank Craighead had showed that grizzly bears ranged widely throughout the national parks and forests.

Dealing with those issues had been hampered by a history of bad blood between the Park Service and the Forest Service. When they created the GYCC in 1964, they did so as part of a broader effort to get along better. The relationship started slowly, and for its first 25 years, the GYCC mostly just provided an opportunity for forest supervisors and park superintendents to meet each other and talk. Still, the personal relationships begun in the GYCC made it easier to create forums outside the GYCC, like the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee.

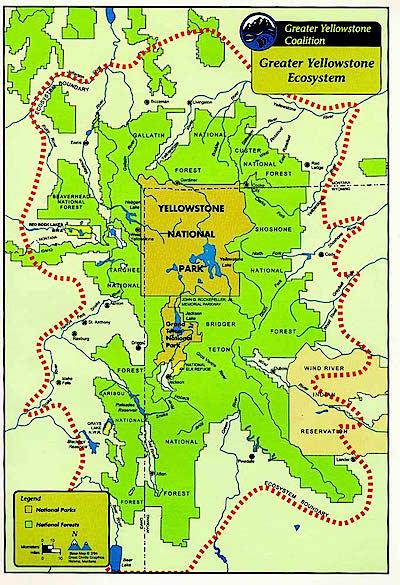

Though they were glad that the agencies were talking to each other about the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, environmental groups thought the GYCC should be doing more. To strengthen their voice, more than 100 environmental groups formed a group, the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, in 1983. The GYC and its member groups got the ear of key people in Congress, and in 1985 a House subcommittee held hearings on the Greater Yellowstone Area. Those hearings were critical of federal management in the region for not coordinating across boundaries and, in many cases, ignoring relevant science.

The Congressional Research Service followed up in 1987 with a study that explored management failures in the Greater Yellowstone Area in more detail. The CRS criticized federal agencies and the GYCC for failing to collect appropriate data, for not sharing the information they had, for not engaging in meaningful cooperation, and for being unable to solve key challenges for the region. It's surprisingly readable for a government report, and it remains a useful inventory of many challenges in the region.

The CRS also took the agencies to task for not investigating how each human activity affected other policy goals. For example, how do different timber harvest strategies affect cattle foraging in national forests? Do hikers care whether cattle are grazing near trails in a national forest? How does recreation, timber harvest, and cattle grazing affect grizzly bear habitat in both national parks and national forests? In 1985, the agencies generally did not know the answers to such questions -- so their planning documents also ignored these externalities. This lack of information presumably increased the negative impact on everything, since the agencies couldn't mitigate impacts they didn't know about.

The GYCC responded to the criticisms with two initiatives. The first, the Aggregation; simply collected information and maps in one place. This project also began an effort to standardize data categories so that agencies were speaking the same language when addressing transboundary issues. This technical exercise was mostly uncontroversial among the many stakeholders in the region.

The second project, the Vision, tried to develop a common vision for the Greater Yellowstone. This would treat the region as a single ecosystem, and think about how each kind of activity affected others. Thinking about impacts across boundaries would presumably have led to efforts to reduce those impacts.

For that reason, high-impact activities such as the oil and gas industry were particularly concerned about the Vision exercise. Hardrock mining and oil and gas development have consistently negative effects on uses such as recreation and wildlife habitat. Timber harvest is more complicated. It has negative effects on some recreational users and wildlife species, but it can create more forage for deer and moose, benefitting hunters and wildlife watchers. Logging roads can provide more recreational access for anglers, campers, and other groups. Federal agencies had not been thinking through those complexities in the 1980s, but started to address them in the Vision.

Focusing on the impact of resource uses had significant political effects. The NPS could not open Yellowstone to mining, oil and gas, or logging. However, the national forests next to Yellowstone could reduce those activities if they affected Yellowstone or the national forests next door. The USFS had this flexibility because its legal mandate of 'multiple use' gives foresters significant discretion to decide how to manage a forest's resources. The NPS usually doesn't have this kind of discretion. As a result, 'coordination' would usually mean that national forest management would move in the direction of national park management, and not the reverse.

The one-sided nature of this coordination shaped stakeholder interests. There was little incentive for resource extractors to support interagency coordination that would almost always hurt their interests. There was also little reason for environmentalists not to support greater coordination. As a result, these two key coalitions could not compromise with each other and support a consensus Vision.

The resource industries had more effective levers in the chambers of power. They used their influence in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho and in Washington, D.C., to kill the Vision. They almost killed the GYCC as well.

*******

After the Vision, the GYCC decided to lay low for a few years. Without thinking in terms of a broader strategy, it formed two subcommittees in the early 1990s, one on Fire Management and another on Invasive Weeds. Both were a response to challenges resulting from Yellowstone's 1988 fires. At the same time, hydrologists began to coordinate at the urging of Luna Leopold, a leading U.S. hydrologist and geomorphologist.

By about the mid-1990s, that kind of technical work had become the GYCC strategy for the post-Vision political environment. Both the agencies and stakeholder groups found some common ground by focusing on narrower, often technical problems. Scientific research, endangered species, wildfire management, backcountry regulations and some wilderness designations have been able to gain support from groups on both sides. People often say that coordinated wildfire management has been a particular success of this kind of work.

Other issues have posed ongoing controversies. Bison, wolves, and snowmobiles remain divisive, and agencies often reach only temporary arrangements or partial solutions. The GYCC has generally not been involved in these controversial issues. Instead, managers have generally addressed those highly controversial problems on their own or through issue-specific partnerships.

The GYCC continues to meet and share information today. In addition, the group sets priorities for the region every two years. The current priorities are Connect People to the Land, Ecosystem Health in the Context of Climate Change, GYA Landscape Integrity, and Sustainable Operations. Those priorities guide staff decisions and help decide how the GYCC allocates about $250,000 a year to projects throughout the region.

Obviously those are pretty broad categories, so it's not clear how much they influence agencies' actual priorities. Since the same agencies both set the GYCC priorities and apply for GYCC funding, it's possible that the process reflects agency goals more than shaping those goals. In addition, that money isn't all that much in the scheme of things. Most budget decisions continue to be made by the individual agencies and land managers in the region, reflecting their own concerns.

As that suggests, the GYCC faces the challenge that its name makes it sound more powerful than it can ever be. The federal agencies in the GYCC ultimately make the decisions, and Congress has given each one a different mandate. The GYCC helps them stay informed on how each unit's decisions affects others, but the decision makers remain the park superintendents, forest supervisors, their regional bosses and Washington offices.

In part because of that political reality, the GYCC has not been very good at engaging the public. It has a website with some information about its work and the work of the national forests and parks that make up the GYCC. The quality of that information varies by working group.

*****

In its 50th anniversary year (2014), the GYCC embarked on a program to engage stakeholders and the public more frequently, and more effectively. This initiative began with two four-hour 'public conversations,' one in Jackson in March 2014 and the other in Bozeman in October 2014.

Those meetings tended to attract highly-engaged and well-informed people, including county and other local officials, both environmental and resource groups, and affiliated Indian tribes. Only a few members of the general public showed up, perhaps because the meetings were held on a weekday and involved a four-hour commitment. In addition, as Coordinator Virginia Kelly points out, the GYCC is not widely known among the general public. As a result, people don't understand why or how to engage with it.

The public meetings made it clear that both organized groups and individual citizens want to be engaged further. They want more information and a much stronger emphasis on communication. They want mailing lists, a Facebook page, a Twitter, and possibly blogs. Though they appreciate the information on the GYCC website, they asked for still more ' data repositories and a clearinghouse for project information, for example. The public would like to see more federal employees engaged in outreach to schools, meeting with officials in the surrounding counties, or lending their expertise in support of other groups' projects. The public also expressed a desire to see public meetings of the GYCC subcommittees, where a more specialized, motivated public might partner with the GYCC more closely on specific projects.

Public talk of partnerships resonated with GYCC goals for these meetings. At the March meeting, GYCC Chair and Yellowstone Superintendent Dan Wenk said that the agencies hoped this conversation would improve federal agencies' collaboration with nonfederal entities such as local counties or non-governmental organizations. Wenk's successor as Chair of the GYCC, Shoshone National Forest Supervisor Joe Alexander, said at the Bozeman meeting that he wanted 'to improve collaboration with nonfederal entities, and to increase capacity through partnerships.' GYCC Coordinator Virginia Kelly also emphasizes that the GYCC is looking for better partnerships as a way to increase its capacity, and the capacity of its member agencies, throughout the Greater Yellowstone Area.

In short, the GYCC message ' partnerships and capacity ' is very clear. The public message ' communicate better ' is also clear. These challenges of communication and capacity have been around since the 1990 Vision project. Though technical work in subcommittees got the GYCC back on its feet, it did not engage people outside the GYCC very well. Only a few subcommittees, most notably the Terrestrial and Aquatic Invasive Species Subcommittees, work regularly with outside organizations.

At the start of its second 50 years, the time is ripe to revitalize the GYCC. Building better partnerships probably starts with better communication. Having public meetings twice a year is a start, but opening some of the subcommittee meetings to the public would provide many more opportunities. Webcasting those meetings would engage people who live far away, as well as locals who might not be able to go from West Yellowstone to Cody in winter, or Jackson to Bozeman. A mediator could take questions from people participating online.

Engaging people on social media would maintain more continuous communication, helping people and groups inform one another of their own projects. That information provides the foundation for more partnerships and capacity building.

These public meetings are a step in that direction. If you'd like to be involved, the GYCC is holding the last of a series of public meetings in Cody, Wyoming, on April 29.

Reading more about the GYCC

Clark, Susan G. 2008. Ensuring Greater Yellowstone's Future: Choices for Leaders and Citizens. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Congressional Research Service. 1986. Greater Yellowstone ecosystem: An analysis of data submitted by federal and state agencies. U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, Committee Report No. 6. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, Publication 67-551.

Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee website, http://fedgycc.org/index.html

Pahre, Robert. 2011. 'Showdown at Yellowstone: The Victims and Survivors of Ecosystem Management,' Journal of the West 50(1): 66-73 (Winter).

Add comment