Welcoming Spring For Three Glorious Days In Great Smoky Mountains National Park

By Kurt Repanshek

Blooms of dogwoods brighten the hillsides of Great Smoky Mountains National Park in spring/Jim Bennett

Horace Kephart roamed the Smoky Mountains in all seasons, but he held springtime here in high esteem.

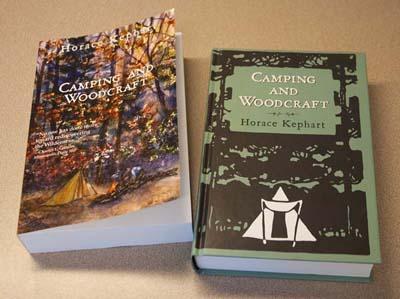

“I doubt if anywhere in the world there is a more luxuriant bloom of of laurel and rhododendron than where I live in the Great Smoky Mountains,” he noted in 1916 in Camping and Woodcraft, a backwoods primer that has gone through some 70 printings.

Kephart kept a tiny cabin for a time on the Little Fork of the Sugar Fork of Hazel Creek, deep in the southwestern corner of today’s national park. A quirky backwoodsman, who at one time had been a librarian in St. Louis, Kephart gained widespread acclaim for the lessons he learned in the Smokies. Today, amazon.com says his two-volume Camping and Woodcraft book “ranks sixth among the ten best-selling sporting books of all time.”

Would the book be so highly considered if Kephart had not learned his craft in the Smokies? Perhaps. But in the landscape of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which was created three years after he died, the ruggedness of the landscape, the wildlife, the trout-filled streams, and the “hells” of laurel and rhododendron provided the wily Kephart with a sturdy backwoods education.

And it, of course, opened his eyes to the beauty of the Smokies. It’s a lasting beauty, one that surely changes through the four seasons, but which burns itself into your memory if you let it no matter the season of your visit.

Kephart spent three years, off and on, on Hazel Creek, during which he explored the mountains and embraced what John Muir would call their “good tidings.”

Though his cabin no longer exists, a mossy millstone stands near his last campsite in the Smokies as a memorial to the man, and you can head down to the Bryson City Cemetery to see his gravesite. You also can head up into the mountains to come to appreciate how he became enamored with the Smokies.

While it might be difficult, if not impossible, to spend three years replicating Kephart’s experience, you can easily sample the wonders of Great Smoky in three days.

Day 1: Explore the Cove

Curling tendrils of smoke wafting from the smokehouse. The clang of a smithy’s hammer on an anvil. Women trading the latest gossip over husking corn, while maple syrup boils down in a cast-iron kettle over an open fire.

Close your eyes while you’re surrounded by Cades Cove and you just might be able to pull these images into your imagination. Settled more than 200 years ago by a young couple hoping for a better life, the cove quickly attracted others. At one point, nearly 700 lived in this bucolic valley that is Great Smoky Mountain’s main attraction (and the crowds attest to that fact).

Cades Cove is a museum of the unique architecture its residents employed/NPS

While the crowds can be offsetting—it can take hours in bumper-to-bumper traffic to navigate the 11-mile loop road that circles the cove—the history here is mesmerizing and the beauty captivating.

Today you might conjure a picturesque setting of tranquility, one that would offer a relaxing escape from today’s wired and politicized world. But before the valley’s residents were ushered out in advance of the park’s establishment in 1934, Cades Cove demanded hard work during long days from the residents as they tended to fields, harvested fruit, ground flour, or repaired their cabins.

While you can drive through the cove in a few hours, savor your visit by lingering over the genius of the cabin construction, the talents needed to shoe horses, the skills for constructing a shake roof or a cane chair. Come early in the morning or stay late in the afternoon and you might spot some of the locals—turkeys, whitetailed deer, or even black bear searching for a tasty apple.

You’ll find a handful of historic structures in the cove, from the cabin of John Oliver, who along with his wife, Lurena, were the first whites to settle here, in 1818, to Baptist, Methodist, and Missionary Baptist churches. There is the John Cable Grist Mill that was built in 1868 and the Tipton Place, raised in the 1880s along with its striking double-cantilever barn.

To escape the traffic yet still enjoy the cove, hikers and cyclists only are given access to the cove until 10 a.m. every Saturday and Wednesday morning from early May until late September.

Day 2: Tranquility in Cataloochee

Across the park to the east from Cades Cove nestle two more communities that were essentially frozen in time when the national park was created.

Cataloochee and its sibling, Little Cataloochee, are similar in setting to Cades Cove, though they have fewer homesteads to explore. Of course, they also have fewer crowds of visitors.

Getting to Cataloochee, which is 39 miles from Cherokee, North Carolina, and 65 miles from Gatlinburg, Tennessee, requires some determination. The 11- mile Cove Creek Road (about 7 miles paved, 4 gravel) runs from U.S. 40 on the North Carolina side of Great Smoky into the valley. Those who don’t have a big rig, and don’t mind twisting, narrow dirt roads, can leave Cataloochee for Little Cataloochee and then on to Tennessee 32 near Cosby (or enter the valley by that route in reverse).

Cataloochee is the quieter side of Great Smoky, yet it offers historic architecture much like that found in Cades Cove. At one point, these two valleys were home to about 1,200 mostly related families.

The Palmer Chapel in Cataloochee dates to 1898 and remains in remarkable condition/Kurt Repanshek

You can spend the night in Cataloochee if you like to camp. A 27-site campground that operates from mid-March through October accepts tents and trailers that are no longer than 31 feet. There are no electrical or water hookups, though generator use is allowed from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Each site has a tent pad, grill, and picnic table. There is a restroom with flush toilets and cold running water.

If you plan to stay the night, don’t forget your fishing pole, as Cataloochee Creek offers a modest trout fishery.

Make the journey into the past and you’ll find a 19th- and early-20th century societal flavor rimmed by 6,000-foot mountains, meadows that fill with elk in fall, and some of the park’s best examples of historic frame buildings from the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Still standing is the Palmer House, a vintage “dog trot” construction featuring two separate log cabins (that later were planked over) tied together by a covered porch where dogs loitered on long, hot summer days. While the house normally doubles as a museum of the valley, it currently is closed until 2018 while renovations are conducted.

Venture to Little Cataloochee and up to the ruins of the Cook Place and Messer Farm and you’ll be standing at the core of what once was the Smokies’ apple empire.

Day 3: Take a Hike

There is no finer place for backpacking and hiking in the East than Great Smoky. Within its 522,000 acres are some 800 miles of trails, enough for you to get lost for a weekend or longer.

You can walk into history by heading for a backwoods cabin, or walk along the roof of the park via the 70 miles of Appalachian National Scenic Trail that passes through Great Smoky. Waiting for your boots are trails that link backcountry campsites, waterfalls, creeks for fishing, and endless miles of gorgeous scenery.

Pay attention during your hike and watch the ground for daffodils that mark some of the many abandoned homesites across the park and help tell the story of mountain settlements. “There is also a remarkable daffodil marker of a Civilian Conservation Corps camp in Cades Cove that outlines the number of the regiment,” says Great Smoky spokeswoman Dana Soehn.

A week of hiking could be planned along the A.T., with nights spent in shelters or tents along the way. Just recognize that spring brings a tide of A.T. thru-hikers heading north from Georgia with hopes of reaching Maine sometime late in summer, and that could mean crowded conditions at shelter sites. Maybe better to leave this for fall.

A way to avoid that tide is to head elsewhere in the park, such as along the Smokemont Loop Trail. It’s only 6.2 miles in length, or day-hike size, but with some help from the park’s backcountry office you can quickly identify other longer, suitable, multi-day treks.

A 6.1-mile round-trip hike along the Little Cataloochee Trail leads to the restored Cook Cabin and the Little Cataloochee Baptist Church.

Now, there are black bears in the backcountry, so be sure to keep a clean camp and utilize bear cables at campsites where Friends of the Smokies has erected them.

Spring is a perfect season to hike the Spruce Flat Falls Trail near Tremont. In early May the mountain laurel bursts into bloom here, and as a bonus you get to enjoy the waterfall.

There also are many short and intermediate trails for casual hikers, such as the gorgeous Abrams Falls and Laurel Falls trails. “Quiet Walkways” are short, easy trails from tiny parking areas. Check with a visitors center for your nearest options.

And if a rainstorm interrupts your stay in the Smokies, grab a copy of Camping and Woodcraft and glean some of Kephart’s woodsman lore for a few hours.

Among the pioneer cabins still standing in Cades Cove is the one built by Carter Shields/NPS

Comments

Sounds like you had a great visit down here, Kurt. Nice article.

Regarding Kephart, however, you won't get much warm fuzzy from true Smokies sons and daughters about him. He is seen as a carpetbagging degenerate who abandoned his large family to pursue and indulge his alcoholism in the hills aforementioned. Old Horace took advantage of Southern Hospitality on many occasions only to turn around and make fun of their "simplistic" lifestyle and capitalize in his books on their backs.

Kurt--I am a native of the Smokies and one of those Kephart described as "branch-water people." I am also someone who has done a great deal of study on and writing about Horace Kephart, I would like to add a few thoughts to your well-written piece on a part of the world I cherish and to the review of Camping and Woodcraft.

First, Kephart is by no means universally liked, much less revered, by folks with roots running deep in the Smokies. All you have to do is look at this list of descriptors he used to describe the "Southern Highlanders" to understand why:In a single chapter in that book, "The People of the Hills," he uses the following words to describe mountaineers: feral, primitive, crafty, strange, intgermarried, slab-sided, stoop-shouldered, sinister, vindictive, sulolen, hateful, suspicious, listless, shiftless, defective, inbred, half-wits, indifferent, unsanitary, gross, and touchy. I would simply suggest that anyone facing that assembly of pejoratives is likely to experience more than a mere touch ot tetchiness. Certainly I do.

In his book Random Thoughts and Musings of a Mountaineer, Judge Felix Alley, a widely respected, well-educated, and indeed beloved man of the mountains, wrote of Our Southern Highlanders: "If Mr. Kephart and Miss Morley (Margaret Morley, author of The Carolina Mountains) had closed their books when they finished what they had to say about the mountains and the mountain region,k and had said nothing about the people who dwell therein, their books would have been acclaimed masterpieces, and we should have owed them a debt of gratitude so great that it never could be repaid. Instead they extend the false impression created by other libelous writers, so that even today multitudes of people . . . look upon our mountaineers as freaks and curiosities." He was squarely on target.

As for the Bernstein review of Camping and Woodcraft, I would agree that appreciable portions of the book are of enduring value. So much is that the case that I successfully nominated him, many years ago, for the inaugural class of the American Camping Hall of Fame. However, there are portions of the book which are highly problematic. His coverage of what he styled "route sketching," for example, is so inaccurate as to in effect provide a tailor-made recipe for getting lost. Similarly, in this book there arises a problem with his inaccuracy when it came to the correct spelling of place names that was magnified many times over (and continues to be an issue to this day) in his work on the Nomenclature Committee which renamed many places in what would become the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Finally, the statement that Libby Kephart Hargrave (not Hargrove, as Bernstein spells it) "has been very instrumental in keeping alive an accurate version of Kephart" is, to put matters bluntly, pure balderdash. Although one can readily understand the filial passion underlying Hargrave's endeavors, the cumulative result of them is often an extended exercise in hagiography.

Jim Casada