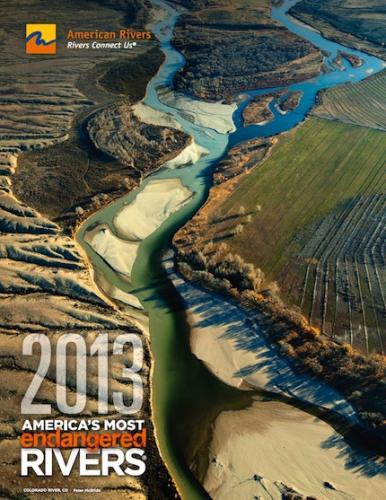

Despite taking in what the Green, Yampa, and other tributaries large and small contribute, the Colorado River is in a death spiral, over-allocated and a victim of growing climate change, left in a state of constant thirst that has made the river the most-endangered in the country, according to American Rivers.

In its annual list of the country's most-endangered rivers, the non-profit river advocacy organization placed the Colorado River at the top of the 10-river list. Trailing it were the Flint River in Georgia, the San Saba River in Texas, the Little Plover River in Wisconsin, the Cataba River in North and South Carolina, the Boundary Waters (the South Kawishiwi River flows into it) in Minnesota, the Black Warrior River in Alabama, the Rough & Ready and Baldface creeks in Oregon, the Kootenai River in British Columbia, Montana, and Idaho, and the Niobrara River in Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

Gaining "special mention" in this year's report is the Merced River that flows from the Sierra Nevada 135 miles through Yosemite National Park to the Central Valley of California. It is threatened, says American Rivers, by a move to rescind some of the Wild and Scenic River designations on the Merced.

Drawing the most attention in the report, though, is the Colorado, which, along with its tributaries, touches parts of Dinosaur National Monument, Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, Canyonlands National Park, Grand Canyon National Park, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, and Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

The problem is too many people, too little water. A report, the Colorado River Basin Water Supply and Demand Study, prepared by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and released in December, pointed out that more water was being allocated from the once-mighty Colorado than it receives.

The average imbalance in future supply and demand is projected to be greater than 3.2 million acre-feet by 2060, according to the study. One acre-foot of water is approximately the amount of water used by a single household in a year. The study projects that the largest increase in demand will come from municipal and industrial users, owing to population growth. The Colorado River Basin currently provides water to some 40 million people, and the study estimates that this number could nearly double to approximately 76.5 million people by 2060, under a rapid growth scenario.

At American Rivers, Matt Niemersk, the group's director of western water policy, was hopeful this year's list of endangered rivers would spur action to reverse that trend and save the Colorado.

“Where we’re at, according to the basin study, the most cost-effective way out of this is to start looking at conservation and efficiency of use of water in the basin. Essentially, the basin study I think is a clarion call for action," he said during a phone call from his Washington, D.C., office. "I think it’s really time for stakeholders, whether they be agricultural, municipalities, individuals, industry, to start to come together and figure out some solutions on how we manage water in the basin."

Photo courtesy of savethecolorado.org.

In justifying the Colorado's No. 1 most-endangered ranking, the organization cited not only Interior's water supply study, but pointed out that "(M)ore dams and diversions are planned, especially in the upper basin in Colorado. Currently, multiple projects are being proposed along the Front Range of Colorado that would remove more than 300,000 acre-feet of new water from the Colorado River and its tributaries –- all of this would be removed even before the river reaches Lake Powell and Lake Mead."

American Rivers' report is just the latest attempt to draw attention and spur action on behalf of the Colorado. In addition to the basin study issued in December, the National Parks Conservation Association in May of 2011 released its own report detailing how dams that dot the massive river basin affect the Colorado.

Some months before that, in August 2010, Jonathan Waterman's book on the river, Running Dry, was published by the National Geographic Society. In his book Mr. Waterman, author of Where Mountains are Nameless, Arctic Crossing, Kayaking the Vermilion Sea, and In the Shadow of Denali, took his best shot to convince local, state, and federal officials -- and all the souls who live from Colorado and Wyoming to southern California -- that there is no possible way the Colorado River can survive, let alone sustain, the demands being made on it.

From his first step towards the river's headwaters along the Continental Divide in Rocky Mountain National Park to his final footsteps "across the scabbed remains of the Colorado River" in the Mexican delta, the author leads us not just down 1,450 miles of iconic river, but points out the too many diversion ditches, dams, and irrigation projects that suck constantly, and increasingly in some areas, from the Colorado.

In its report, NPCA said the series of dams that interrupt the Colorado River in its flow from the high country of Rocky Mountain National Park down to the Gulf of California has altered nature by constricting high runoff flows, artificially enhancing low flows, changing sedimentation patterns, and even impacting water temperatures to the detriment of native fisheries.

Meghan Trubee, who works on Colorado River issues for NPCA, on Tuesday shared hope with her colleague at American Rivers that greater public consciousness about the river's plight was spreading.

“With the appointment of Sally Jewell as the new (Interior) secretary, with the 'Next Steps' discussions from the basin study that are still in formulation, I think people are beginning to get it, but it seems to me that there’s still a lot of work to do to get the message across," Ms. Trubee said. "The basin study is a very technical and complicated document that is not an easy read for somebody who is in the business, and even more so a more difficult read for an everyday peson. So I think we need to do a better job of getting the word out there. I think it’s starting, too, but the crescendo is still at the smaller end in my mind."

Unless the current trend is reversed, the national parks in the Colorado Basin will see more and more impacts, ranging from declining health of riparian corridors to increased exposure and erosion of archaeological sites, the NPCA official said.

"You will always have water flowing through some park units because of (Colorado River) Compact delivery obligations at Lee's Ferry. So, to some degree, you can count for a certain amount of water to always go through the parks," Ms. Trubee said. "But there’s the potential to have death by a thousand cuts by additional water diversions happening adjacent to parks that may reduce water above and beyond the predicted decrease from climate change."

The most-endangered rivers in American Rivers' 2013 report.

Whether it can be attributed directly to climate change, or simply a drought, the snowpack at the river's headwaters in Rocky Mountain National Park has suffered this past winter. While the average snowfall totals taken in the park at Bear Lake from November through April since 1983 has been 226.83 inches, this year's snowpack stands just under 172 inches after a storm earlier this week dropped 29 inches of snow at the lake.

"Overall in the basin I think precipitation is about in the 75 percent average range. But that’s compounded, because we’ve been in that range the past dozen years or so," said American Rivers' Mr. Niemersk. "That’s really having an impact on reservoirs and the water supply. Places like Lake Mead and Lake Powell are at, or just below, 50 percent of capacity right now. And demand for that water is going to continue to increase.

"I think the thing here going forward is that we’ve got to come together, figure out some solutions, and while at the same time protecting the health of the river and its tributaries. There’s a lot of instream benefits that are derived form keeping healthy flows in rivers, and that’s got to be part of the equation as well.”

Urging Congress to take an approach with the Colorado River watershed that it has with the Everglades and the Great Lakes, where congressionally funded restoration programs are in place, would be a logical step, both Ms. Trubee and Mr. Niemersk said.

"I think it’s hard because the Colorado River Basin is so huge. It’s what, roughly 20,000 acres less than the size of Texas?" said Ms. Trubee. "It’s a massive, massive, area. I think there needs to be an authorization like the Everglades has and the Great Lakes has. And, actually, NPCA has been at the forefront of helping to develop those and keep the authorization for the funding for those moving forward. ... We are very supportive of trying to move an idea like that forward.”

Mr. Niemersk said the success of the programs for the Everglades, Great Lakes, and Chesapeake can be attributed to bipartisan support for the restoration efforts.

“Traditionally, the Colorado River Basin politically hasn’t operated that way," he pointed out. "I think the nature of the resource out there has always pitted state vs. state, make sure you get what you can. But that needs to change.

"I think, going back to the basin study, what it says is we’ve got a problem and we have to work together to solve it. And it’s incumbent upon the members of Congress to come together and begin to take a leadership role in making sure those resources that can be available get to the people, localities and states, to do the good work to bring stakeholders together on the ground to start addressing some of these problems.”

Comments

In the meantime, a proposal to extend a large volume pipeline from Lake Powell to St. George, Utah is still alive and rattling around somewhere. One Utah legislator was quoted as saying something like, "We can't let all the water that has been allocated to Utah get away from us."

Many years ago, I was told that on any given summer day, six inches of water per day is evaporated from the surfaces of both Lake Powell and Lake Mead (and the other lakes below Mead). Evaporation loss from Lake Powell alone was supposedly enough to quench the daily thirst of the Los Angeles basin. (I admit, I've never tried to verify that. But it sounds logical.) Down where what little is left of the Colorado as it crosses into Mexico, the water has become quite saline due to evaporation upstream. When I've visited Yuma, I've seen reports in local papers expressing concern that the increased salinity is harming crops down there.

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.

John Muir

When will we finally begin to understand the truth of that? (Or are we even willing to consider it?)