Perhaps few people today remember Nancy Ayers, but I will never forget her. Certainly, on being informed of her death last winter, a flood of memories came rushing back.

Yes, it has been that long. From a modest home in a suburb of Binghamton, New York, Nancy spent the 1960s and 1970s campaigning for environmental education and public parks. Thanks to her, both became pillars of my career, as well.

In her honor, I decided to reread Polly Welts Kaufman's National Parks and the Woman’s Voice. Although I recalled no woman in the book quite like Nancy, I owed it to her to reflect on our friendship. A book reminiscent of her qualities seemed the perfect touch.

I had already thought back to the day she asked me to join the board of the Susquehanna Conservation Council. It was early summer of 1966, and she was casting about for new members and allies.

“Al, we need you,” she said. “We need young people from the university. This just can’t be an organization of society types with nothing else to do.”

She meant Harpur College of the State University of New York at Binghamton (now Binghamton University), where I had just completed my freshman year. Most students there, I reminded Nancy, were obsessed with the war in Vietnam. Her campaign to clean and beautify the Susquehanna River—including the establishment of a 17-mile riverbank park—was certainly not their highest priority.

“I realize that,” she replied, “but from everything you have said at our meetings, I am confident it is yours. And one day, when the war is over, I believe those students will come around.”

It took a few more years, but she was right. On graduating in 1969, I was among the thousands still facing the draft. However, Richard Nixon promised eligible men a lottery. The war at least appeared to be winding down.

As suddenly, students were going over to the environment and chanting “Kill the car!” Certainly by Earth Day, April 22, 1970, “Stop the war!” was in second place.

Zealots that first Earth Day buried V8 engines, and on a few campuses entire cars. Fortunately—and just as Nancy had hoped—Harpur College exhibited some common sense.

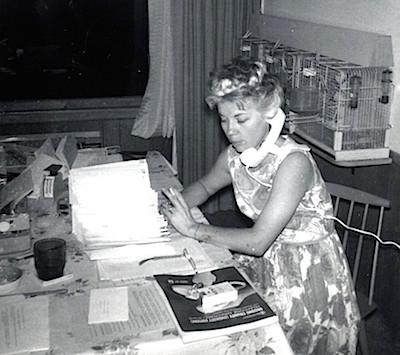

Shown in 1966, Nancy Ayers staffs the headquarters of the Susquehanna Conservation Council—her dining room table and “desk.” The birds in the cages are zebra finches; the cigarette in her hand is a Kent. Not shown: her canary, a husband, two daughters, and a son—and a doctor urging her to give up smoking, which she repeatedly attempted but never did/Ayers Family Archives

There the issue remained a campus marsh and forest and the destruction of several acres of old-growth trees. After draining the marsh and removing most of the forest, the administration promised a new ring of playing fields.

Informed throughout by the Susquehanna Conservation Council, students successfully rallied for a permanent nature preserve instead.

Battle for the Susquehanna

Through Nancy, I similarly learned how to influence government creatively, not simply protest it should work in a different way. As one outlet, Binghamton had two daily newspapers, the Sun-Bulletin and Evening Press.

“Think how many people read letters to the editor, Al.” I should write a few, she advised.

More to the point, someone needed to challenge our congressman, Howard W. Robison, to explain why he wanted to dam the Susquehanna River. On just Binghamton’s North Branch and its tributaries 25 reservoirs were being planned. After winning a $3 million appropriation from Congress for a study [$15 million today], he had handed off the project to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Consequently, in 1968 Congress had agreed to remove the North Branch of the Susquehanna from possible inclusion in the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

Once the significance of that omission became apparent, I described the details in a letter to the Evening Press. When Congressman Robison answered my letter, defending the dams as “scenic,” I instantly fired back.

“How, Mr. Robison?” the Press headlined my second letter. How will dams make the river more beautiful? Including a photograph of the riverbank in Binghamton, my response—now in the Sunday edition—stood out atop the editorial page.

Nancy loved every minute of it. “You sure got his attention!” she exclaimed. “And the public’s.”

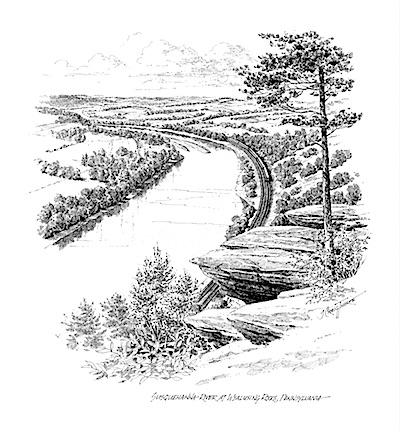

After passing Binghamton, the Susquehanna continues west, then abruptly heads south into Pennsylvania, splitting the Endless Mountains in a sweeping arc. A popular viewpoint is Wyalusing Rocks, shown here in an etching by J. Craig Thorpe. Corps of Army Engineers proposals for this part of the river included a series of slack-water dams—possibly a cooling source for nuclear power plants/Courtesy of J. Craig Thorpe

Of course, my approach had been vintage Nancy Ayers. In a pitted environmental battle, you have to raise the stakes.

She knew she would never get a 17-mile park bordering the Susquehanna, “but our primary objective,” she later wrote, “was to generate controversy on the subject and to make conservation benefits visible to the general public. What they don't see as a direct benefit, they are not likely to understand or support.”

“A riverbank park would come within a mile and a half of 80 percent of [Broome] county's population for hiking, fishing, boating, swimming, biking, picnicking, and just plain resting. If anything will ever catalyze interest, this should be it.”

If getting noticed was half the battle, the other half—staying noticed—was no less critical in order to see the battle through.

“Remember, both the press and the public have short attention spans,” she remarked. “Before you know it, you’re yesterday’s news.”

The Purple Lady

Nancy’s personal solution to that proved masterful. A lifetime fan of purple, she creatively fashioned the color into her business card, dressing in shades of purple from head to toe.

At first, I thought the lavender hair a bit eccentric; however, I soon realized the joke was on the press. She knew reporters would label her—perhaps even make fun of her. But no one in government would fail taking notice.

“Isn’t that Nancy Ayers? The one they call The Purple Lady?”

Sure enough, some reporter at the Evening Press couldn’t resist a jab. You mean “The Purple Grackle,” he wrote.

Nancy refused to bite. It was after all her strategy. “Although I would wear purple in any case,” she admitted, “it is important to be remembered after you leave the room.”

One day “the room” would be a panel of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the next a hearing before the county or state legislature. Her point remained: If anyone had to ask her name, she was already at a disadvantage.

Called forward to the hearing table, she then let the purple fly. Especially after passage of the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, she knew exactly what to propose for our river.

“Gentlemen, I thank the Army Corps of Engineers for inviting me here today. However; and you will pardon me for saying this: Can you think of nothing but building dams?”

“Think instead what a free-flowing river means to our community—any community. You talk about flushing the river when it is low—low-flow augmentation, I believe you call it. What is that all about? We should be ending pollution at the source. Harrisburg doesn’t want our garbage. Nor will all that flushing save Chesapeake Bay.”

“When the river is low, it is supposed to be low. It only needs to be clean. We need better sewage treatment and riverfront parks, and yes, what Congress now defines as a scenic river. Dams will only destroy its beauty.”

It’s been 50 years; my quotes here are approximations. However, whether expressed in letters or public hearings, all are true to the facts. Always prepared, and always a terrific speaker, Nancy knew how to take “the system” on.

Well do I recall a colonel with the Army Corps of Engineers who asked what she knew about building dams. Her response never missed a beat.

“Building dams? Why, nothing,” she admitted, “nor has that ever been the point. The point is a healthy river. Congressman Robison may believe in dams, and you may think they offer benefits. But tell me, among all of those alleged benefits, which one protects the beauty we have right now?”

As for dissecting the Corps’s final study (a whopper), Nancy assigned that task to me. “You’re the historian, Al. Tell the community what this controversy has been all about.”

Forever in love with purple. Nancy Ayers (1928-2015) in 2014/Ayers Family Archives

She then asked the editor of the Sun-Bulletin to publish my analysis, which he did—starting on the front page and including two full pages as a center spread. Nancy did the fact-checking and peer review.

Published March 12, 1971, as “The Susquehanna: Use with care,” it was the catalyst, the editor later assured me, for convincing the Corps to fold its tent.

Parks for the Future

For Nancy, the article meant vindication, nor did she waste the opportunity. She was already deep in her next campaign—the expansion of county parks. Broome County’s rolling, wooded hills and dairy farms were beautiful to look at, but for the most part privately owned.

Especially children from the inner city needed public places to hike and swim. Nor should it take more than a county bus to get them there.

Before anyone could say park, Nancy had convinced the county to establish five. The number today stands at nine. The Purple Grackle had scored again.

Following Earth Day, she herself put a renewed emphasis on education, including a name-change for the Susquehanna Conservation Council. Henceforth to be called the Susquehanna Environmental Education Association, it was still her organization through and through.

Nancy’s point—and the point of history—is that education remains the key. Even today, New York State prides itself on a history it could just as easily have cast aside.

In the 19th century, it had taken reformers, i.e., educators, to insist that cutover lands in the Adirondack and Catskill Mountains revert to the state as forest preserves. Again covered with mature trees, they are among the finest in the Northeast.

Starting with Niagara Falls, purchased in 1885, a magnificent system of state parks came right behind.

In stark contrast, Nancy’s generation seemed bent on sprawl and pollution. Even the storied Hudson River had become a sewer. She just had to help put a stop to that.

Women and the National Parks

This is to explain what I find reassuring—and I will admit nostalgic—about National Parks and the Woman’s Voice. In my still impressionable years, I was privileged to be mentored by one of the finest women I have ever known.

That said, I never heard Nancy assert that women are “different,” as in so different as to be more “effective.” Although she relished her role as the Purple Lady, she realized that men could play an audience, too.

As for the rest of it—the common assertions that women are better listeners, better team-players, better negotiators, better care-givers, better “carriers of culture,” again, Nancy stuck to observable facts.

By the 1970s, American women were also wearing power suits and pursuing careers in business. Not every woman “listened” to the environment; or “cared” for it; or “nurtured” it, to say the least.

It was enough, Nancy agreed, to set the record straight. And yes, where Polly Welts Kaufman corrects my ommisions, I believe I hear Nancy chuckling.

“Admit it, Al. You forget me! Your book says nothing about my campaign for a scenic river on the Susquehanna.”

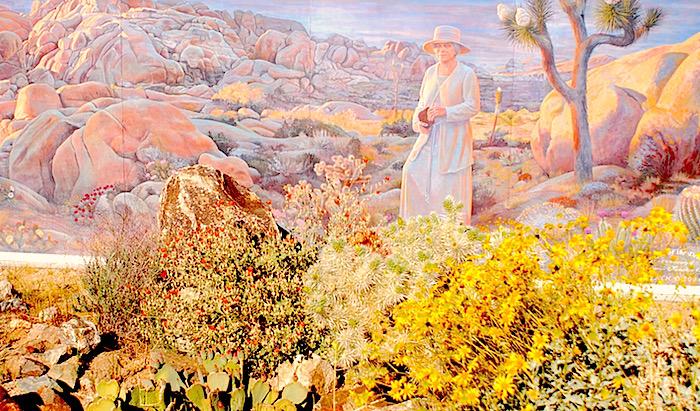

“Okay, including me may be a stretch, but you say nothing about Minerva Hamilton Hoyt. She only saved one of your favorite national parks, Joshua Tree, initially as a national monument.”

Of course, I am now playing to my audience. Nancy never said any of those things.

When last we talked, she was proud of her place in history and knew exactly what the history was. She would have accepted that Joshua Tree, like our beloved Susquehanna, was not pivotal to the national park idea. The pivotal parks, which were hardly every landscape, are what National Parks: The American Experience is all about.

Did the pivotal players do all they could have done? That is debatable. But there is no denying who those players were.

To her credit (at least initially), Professor Kaufman resists bombarding us with obscure women as a counterbalance to those famous men. The women she discusses really mattered, if not always in Act One of the history.

Minerva Hamilton Hoyt's successful campaign for Joshua Tree National Park is remembered in a mural on the side of the park's visitor center/Kurt Repanshek

As activists, they may not have known John Muir—or read his writings—but many indeed finished his campaigns. As significant (as if we should be surprised), we learn that women conservationists sought out every willing ally, eagerly enlisting men—as did Nancy—in any of their campaigns.

Fighting for Everglades National Park, Marjory Stoneman Douglas and Ernest F. Coe became a team. Securing the rain forests of Olympic National Park, Rosalie Edge, Irving Brant, and Willard Van Name were a team.

Did they always agree? Of course not. There were indeed hurt feelings and falling outs. However, when the chips were down—when the developers were rattling their sabers—they knew to fight side by side.

The second half of the book thus seems tedious, although Nancy might disagree. She believed in compiling the record before editing any of it. Perhaps all of the names and Park Service “incidents” are needed at this point, even those sounding like pure complaints.

As for inflating the record—the common assertion in women’s history that women are innately “better” at many things, I know Nancy would raise her eyebrows along with me. At least, don’t muddle your campaigns, she would advise.

Naturally, Nancy took full advantage when important issues complemented one another, for example, the linkage between preservation and civil rights. Poorer children (although not just African-American children) deserved good public parks.

To be sure, she ultimately preferred to say just children. Why should there be a modifier every time?

Where activism was called for, modifiers risked turning environmentalists into scolds. Playing the Purple Lady to effect was one thing; never being satisfied with the outcome quite another.

She would in fact leave Binghamton in 1974, concluding her career with the New York State Senate in Albany. However, it was not because Nancy feared she had worn out her welcome. It was rather because she had won.

The Men’s Club

To her good fortune, still the term political correctness was not in the dictionary. Unlike today, no one tried convincing her that parks are socially “wrongheaded” and that actually she had lost.

For the most part, Professor Kaufman avoids that trap; however, it does occasionally spring shut with a jolt.

Granted, the National Park Service began as a militaristic, male-dominated organization. After all, its inspiration was the military, specifically, the cavalry that between 1886 and 1914 had patrolled Yellowstone, Sequoia, General Grant, and Yosemite.

However, consider how men in the Park Service fared. Most were so miserably paid they trapped fur-bearing animals, while shooting predators to get the bounties.

Women aside, how many men wanted to be a part of that culture, either? In describing the early Park Service, Professor Kaufman describes a code of behavior that intelligent men found repugnant, too.

Certainly, until a semblance of biological order came to the parks, no one of intellectual bearing had it easy. That especially went for educators trying to instill reform.

What made people like Rosalie Edge so effective? And later Nancy Ayers? They saw clearly that the parks movement depended on intellect. It had nothing to do with sex.

Smart men were also pilloried. How dare Joseph Grinnell, that “grackle” from the University of California, say rangers should not trap in the national parks? How dare he embarrass the Park Service—in professional journals, no less—by insisting that predators are worth saving, too?

Only because he persisted—chipping away at the Park Service hierarchy—did scientists finally get some respect. When next a few were hired (and indeed, it was just a few), he hoped their intellect would chip away from within.

What makes women think they stand alone? Intellect is always a burden in the workplace when someone of lesser intellect is opposed.

As it stands, opportunities for both men and women in the Park Service have slipped precipitously, if by opportunity we mean policies calling for intellect and not just the party line.

The big slippage is interpretation, now increasingly given over to “volunteers.” Is that because the Park Service is still short of women, or rather because the culture still prefers consensus?

This is to explain where women’s history consistently loses me. Fine, credit women with “breaking into” the Park Service—or any other organization. But then as boldly address the bigger issue: Do women alone bring an increase in intellect?

Weak cultures define women, too. Especially in government and education, you don’t always get the best people just because some people are allowed to claim they are the best.

More likely, you get the people who know how to “hang on.” Ultimately, that is how women “broke into” the Park Service. They finally got the means to “hang on.”

And what was the means? Of course, the pill. Up until 1960, the common means of birth control was Vatican Roulette. In college, I certainly spun the wheel, as did most of the women I knew on campus.

Within a decade, the pill was ubiquitous. Agreed, bashing the obstinacy of the National Park Service has more drama. The battle of the sexes is the one that sells. But there it is—what ultimately freed a critical mass of women to take their place in the professional world.

Did the Park Service hierarchy resent that? Absolutely. But here is where history needs to be careful. Again, the point everyone dances around is intellect. A bureaucracy resents criticism from any source. Men critical of the agency were held back, too, that is, if they even got past the application.

After all, that is how a bureaucracy survives. Don’t rock the boat. Even among those women who think they rocked it on their own, history proves they had allies.

Rarely without a smile—a source of great comfort to her patients—Dr. Jeanne Petrek soaks up the beauties of Joshua Tree National Park/Jeffrey Duban

And finally, the pill. Admittedly, not all women faced getting pregnant, but the majority most certainly did. Until they were secure, women of any sexual orientation were going nowhere, any more than gay or bisexual men.

As it stands, this making of everything in America into a competition has gotten out of hand. Preservation is a calling, not a competition. As Nancy would say: Battle change, not one another. If you are that unsure of yourself and your mission, stay home.

Jeanne A. Petrek, MD

The late Jeanne A. Petrek, a distinguished breast surgeon from New York City, adds another poignant reminder of what the mission is. Several times a year, after visiting their son in California, Jeanne and her husband Jeffrey looked forward to spending a day or two in Joshua Tree National Park. Keys View was Jeanne’s favorite.

All too soon back in New York, she resumed her duties as a surgical oncologist at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. She was also a professor of surgery at the Cornell University School of Medicine, and further, as a research scientist, was completing a 10-year study of the effects of breast cancer on pregnancy and fertility.

Has there ever been a better example of intellect, and what it means to have national parks?

On April 11, 2005, Jeanne died tragically on her way to the hospital. A year later to the day, friends and family gathered at Keys View in Joshua Tree for a special memorial service and the scattering of her ashes.

It was a morning still imbued with hope, dawning with the knowledge that Jeanne had saved thousands of lives—and would save countless more through her completed research.

This is what the founders were after. No doubt, Jeanne would forever be an inspiration. However, as she herself confirmed by loving it so, Joshua Tree was her inspiration.

Again I hear Nancy’s voice. If some people would now make the parks into a competition—any competition—perhaps it would be best if they stepped aside.

As for the Park Service, it needs to step up. Especially in today’s troubled, narcissistic world, there is no end to the parade of supplicants insisting that the parks become something less than parks.

Every such dilution risks the intellect needed for intellect itself to prevail. The sacred purpose of parks—inspiration—can only survive if they remain inspirational.

Read in the proper spirit, National Parks and the Woman’s Voice invites such clarity. Are women “better” conservationists? Nancy was, but then, she would have been better at anything. And Jeanne. Fortunately, still the heart of public service—dedication—has never been a sexual trait.

A frequent contributor to the National Parks Traveler and author of National Parks: The American Experience (Taylor Trade), Alfred Runte writes further about American rivers in Allies of the Earth: Railroads and the Soul of Preservation (Truman State University Press).

Comments

This was most inspirational on a Sunday afternoon, and I totally agree that Gender has less to do with compassion for the park experience, than dedication, vision, and commitment. These women want to be known for being selfless in these works, and focused on what they were trying to accomplish against a wall of old ways of thinking, doing, being, sometimes called "hardening of the categories" for the academic bunch.

We now need to separate inspiring places from recreational outbursts (OHV) and event based entities.

Calling everything a "park" is part of the problem. What we are preserving is spirtual and does not require governmental interventions nor social metrics to justify keeping them open. Thank you for capturing her voice and the color purple, farthest in the spectrum needing to be seen.

Well done Al and a wonderful tribute to Nancy Ayers. I wish I had the opportunity to meed and know her.

Harry Butowsky