Canoe at sunset, Lobster Lake in Maine North Woods / George Wuerthner

Editor's note: With the National Park Service's centennial soon upon us, National Parks Traveler is rolling out its Centennial Series, a collection of papers that touch on aspirations and note inspirations for the agency and the world's greatest collection of parks in the coming 100 years. We kick off this series with the following from Robert B. Keiter, the Wallace Stegner Professor of Law, University Distinguished Professor, and founding Director of the Wallace Stegner Center for Land, Resources and the Environment at the University of Utah S.J. Quinney College of Law.

The National Park Service Centennial in 2016 presents an important opportunity to reflect on the system’s enormous growth and change since its inception. From a mere handful of national parks scattered across the West in 1916, the system now exceeds 410 units stretching across all 50 states and covering roughly 84 million acres. It contains national parks, monuments, preserves, recreation areas, seashores, battlefields, and heritage areas along with nearly a dozen other specific designations, all deemed nationally significant enough to merit a place in the system. In 2014, Congress commendably added another seven units to the system, and the President has since added several more national monuments. These actions confirm that this revered national treasure is not complete, and raising the prospect that the centennial itself might yet see more additions to the system.

The spectacular growth in the national park system presents the question of how additions come about and what might be done to prompt further additions as we move into the system’s second century. Under existing law, Congress and the President are each empowered to add new units to the national park system; the Congress through its usual legislative process, and the President through the Antiquities Act, which gives him authority to proclaim new national monuments on public lands. A new park designation decision is thus inherently a political matter that is in the hands of our elected federal officials. It is not a prerogative of the National Park Service nor of state or local officials, though each can certainly promote new additions to the system as well as a vision for the future. More often than not, as Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan reminded us in their sweeping PBS documentary series, new national park designations have come about through aggressive citizen advocacy prompted by a few foresighted individuals committed to protecting these special places.

Stephen Mather, the first director of the National Park Service/NPS

One person who understood these political realities was Stephen Mather, the first Director of the National Park Service, whose tenure and insights set the tone for the agency over the ensuing years. As we ponder further expansion of the national park system during its second century, we can learn from Mather and his unabashed commitment to promoting the nascent system by supporting efforts to attract visitors to the parks. Occasionally criticized for his booster-like initiatives, Mather was intent on bringing Americans to these special places, convinced that once they had experienced a national park they would appreciate its value and support the new system. He understood that in the world of politics, public support was essential to ensure the system endured and prospered, whether the issue was budget appropriations for infrastructure, new national park designations, or the expansion of existing ones.

Mather’s seminal policy document, the so-called Lane Letter, plainly reflected this commitment to public engagement in the fledgling national park system, as well as his steadfast commitment to conserving these special landscapes. While establishing as a first principle that “the national parks must be maintained in absolutely unimpaired form,” the Lane Letter also spoke in terms of a “national playground system,” encouraged recreational use of the parks, called for low-priced camps and reduced automobile fees, and encouraged the new agency to cooperate with the “western railroads… chambers of commerce, tourist bureaus, and automobile highway associations.” Moreover, Mather endorsed an array of booster-like initiatives, including public bear viewing spectacles, a park zoo, ski areas, swimming pools, and even golf courses—all in an effort to bring people to the new parks.

With this background, it was no surprise that the National Park Service celebrated its 50th anniversary with Mission 66, the most ambitious construction campaign in the agency’s history. Designed to expand and upgrade park facilities to accommodate the flood of visitors expected in the aftermath of World War Two and the baby boom, Mission 66 garnered substantial political support and significantly improved the built infrastructure inside the parks. It did little overtly to advance the agency’s nature conservation agenda, but it did bring Americans to the national parks in record numbers, a trend that generally prevailed throughout the remainder of the 20th century. It also helped ensure they had a memorable experience once there.

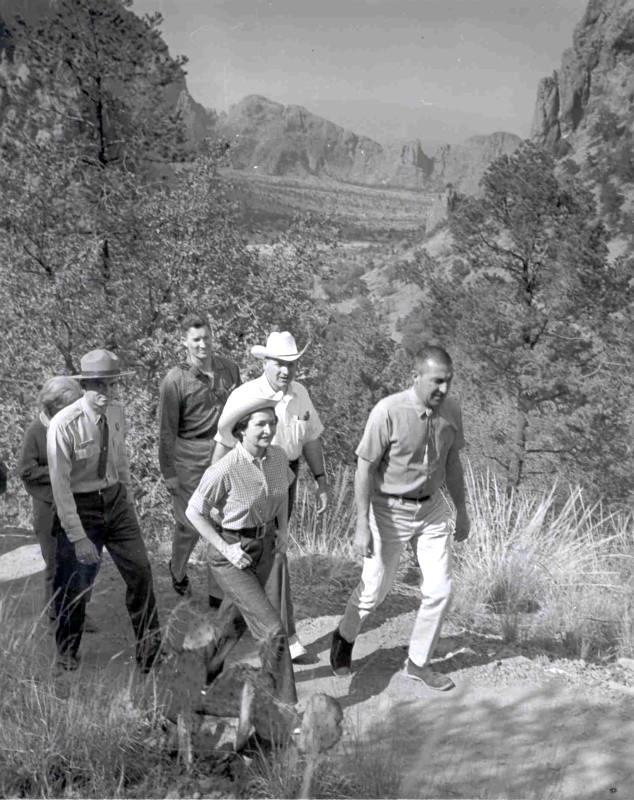

During the Mission 66 years, some 60 new areas were added to the national park system. And in the immediate aftermath of Mission 66, the system experienced another growth spurt under Director George Hartzog who helped to shepherd more than 72 new national park units through Congress in the period from 1964 to 1972, widely recognized as a golden era for the national parks. Since then, with the notable exception of the 1980 Alaska additions (for which much of the groundwork was laid during Hartzog’s time), national park system growth has been haphazard, and very few large national parks have been added to the system. Although Congress was persuaded in 2014 to further expand the system, only the Valles Caldera addition in New Mexico represented a natural area that contained any significant acreage.

National Park Service Director George Hartzog (cowboy hat) follows Interior Secretary Stewart Udall up a trail at Big Bend National Park / NPS

Several factors help explain this lack of extensive recent growth in the system, especially the absence of new large “national parks.” Since the 1960s, the option of alternative protective designations—wilderness area, national conservation area, and the like—has been available to protect sensitive and attractive lands, rather than creating a new national park unit. (Ironically, these alternative protective designations were developed in part as a reaction to the Park Service’s early penchant for overbuilding in the national parks.) Intense agency turf battles, particularly between the Park Service and the Forest Service, have frequently blocked proposals to transfer national forest lands to the Park Service, while the new National Landscape Conservation System has given the Bureau of Land Management a much more prominent role in land conservation. Because many new park designation proposals involve lower elevation lands with conflicting uses, such as livestock grazing or energy production, there is typically more potential for conflict over proposed new additions today than was present in the past. Moreover, public land preservation efforts, whether in the form of new national park or wilderness area designations, have become a political lightning rod across much of the West, often serving as a wedge issue between economic development advocates and land conservation proponents.

The centennial, however, represents an unparalleled opportunity to enhance the system to meet the challenges of the 21st century. In 2009, a blue ribbon Second Century Commission (which included current Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell among its members) recommended creating “a national conservation framework” with national parks as the “keystone” to promote “representation of the nation’s ecological diversity” and “to broaden the diversity of our national narrative to reflect our nation’s evolving history.” The National Park Service Advisory Board has urged the agency to “identify gaps in natural resource representation, focusing especially on opportunities to improve habitat connectivity, to leverage additional protection in large landscape-scale conservation efforts, and to employ restoration strategies,” while also evaluating opportunities to “tell the whole American story” through new cultural and historic designations. And the National Park Service, in its own second century document, has called for “a national system of parks and protected sites … that fully represents our natural resources and the nation’s cultural experience.” The agency, though, has focused its centennial initiatives primarily on attracting new visitors, engaging youth, and extending its education programs with little public mention of adding new units to the system.

Valles Caldera National Preserve is the only natural area with significant acreage that has been added to the National Park System in recent years / NPS

Despite the Park Service’s lack of focus on new park creation opportunities, its commitment to engaging diverse new constituencies and the younger generation in the national parks may pay long term dividends in the form of new park designations or expanded conservation efforts. As the nation’s population continues to diversify, political power will inevitably shift as traditional minority groups gain greater influence by virtue of their sheer numbers. If these citizens have not experienced the national parks and lack interest in the system, the parks will enjoy little political stature among this potential constituency. If the nation’s young people have no exposure to the outdoors, they too will see little benefit in a national park system as they become engaged members of the political community, surely reducing the number of congressional champions willing to support or expand the system.

If the National Park Service succeeds, however, in engaging new constituencies and the younger generation in the national parks, it will be grooming new champions for the system. And if the Service’s efforts to integrate more education programs into the national parks succeed, it will help to maintain an informed constituency that can understand the system’s value and carry that message into the political arena. By reaching out to new and increasingly important constituencies, the agency is helping to build the political base that will not only ensure the national park system for the next century but can also prompt its expansion. In short, the Mather approach of enticing new visitors to the national parks in order to win their support for the system may well hold the key to long term future growth in the system.

Expansion of Canyonlands National Park, to encompass the distant landscape seen through Mesa Arch, long has been called for / NPS

The additional steps necessary to connect the agency’s centennial constituency building efforts and systemic growth are seemingly evident. First, in order to attract new constituencies to the national parks, the system must be relevant to them. The Service must therefore ensure that African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians, women, labor, LGBT individuals, and other historically marginalized groups find their experiences represented in the system and their stories told as part of the nation’s cultural heritage. This means integrating these stories into the conventional narrative at existing park locations, and it argues for new relevant designations to ensure all groups are represented in the system. Second, the agency’s efforts to attract younger people and more diverse audiences to the national parks suggests the need for park units near heavily populated urban areas. This would provide an opportunity to introduce these constituencies to our natural heritage, and to explain why nature conservation is essential to our nation’s future, especially in light of the climate change threat and mounting biodiversity losses. If successful in conveying these messages, the Park Service will set the stage for new park additions as a means for expanding the nation’s natural and cultural conservation commitment.

There are, of course, evident impediments to growing the national park system in today’s world. Historically, large new acreages have been added to the system by re-designating national forest or BLM public lands as new units of the national park system, either by congressional legislation or presidential edict. But this approach to expansion has never been popular with these two land management agencies, which have long resisted such intrusions on their turf, accusing the National Park Service of snatching away their most spectacular lands. Today, these agencies argue, with some legitimacy, that they can adequately protect their own special lands as wilderness areas, national monuments, or through other protective designations. Yet these agencies do not ordinarily bring the same level of oversight or services that are available in the national park system. Indeed, a national park label carries with it several advantages, including adequate law enforcement resources to protect sensitive areas, extensive experience with public educational and interpretive programs, and the related likelihood of engaging new and more diverse constituencies.

This is not to suggest that every special place on the federal landscape merits national park designation. Rather, it highlights the need to coordinate the nation’s conservation efforts, including better communication and collaboration among the federal land management agencies and with their state and tribal counterpart natural resource agencies. Most knowledgeable observers agree that the nation, facing very real global climate change threats and escalating biodiversity losses, must adopt a landscape-scale approach to nature conservation. Besides necessitating better coordinated planning and resource management decisions among the agencies, landscape-level conservation will require new and redundant protective designations that include unrepresented ecosystem types and connective corridors to enhance resiliency and to enable displaced species to move to new habitat. In this effort, new national park designations linked to the larger landscape would certainly be helpful. Or these concerns can be addressed by alternative protective designations along with more concerted efforts to plan and manage collaboratively at this larger landscape scale. These points—including a reference to national parks as “critical anchors for conservation”—were made forcefully by Secretary of the Interior Jewell in a recent speech designed to reset the nation’s conservation agenda for this new century.

Regardless of the force of these arguments, any new park designation decision will involve political judgments, which means proponents must be prepared to convince Congress or the President to take action. Although former House Speaker Tip O’Neill once famously observed that “all politics are local,” the national park system is by definition a national concern, but one with obvious local overtones. By law, proposed additions to the national park system must meet a “national significance” standard as well as related “feasibility” and “suitability” criteria. These terms are defined broadly, however, and the National Park Service enjoys considerable discretion in giving content to them. Moreover, Congress regularly ignores these criteria when it wants to establish a new park unit.

Looking at the evolution of the national park system, it is quite evident that our collective view of what constitutes a “nationally significant” landscape or site has evolved, reflecting the prevailing values and concerns of the time. In today’s world, addressing climate change and biodiversity losses are plainly national goals, just as promoting cultural diversity, environmental literacy, and outdoor recreation are important concerns in our increasingly urbanized world. When well-documented economic arguments extolling the financial benefits associated with a national park designation are added to the mix, the stage should be set for congressional action. But if Congress cannot be persuaded to act, then President Obama, who has proven through his national monument proclamations that he is sensitive to these arguments, has the authority to take action under the Antiquities Act to establish additional national monuments.

While the National Park Service’s centennial efforts are taking a long term view, the nation has immediate conservation needs and opportunities. Several new national park proposals have been advanced with substantial public support that would meet the concerns noted here. One is for a new national park unit in central Maine. Consisting of privately owned lands that would be donated by the land owner to the National Park Service, the so-called Maine Woods proposal envisions a 150,000 acre joint national park and recreation area designation. Situated adjacent to Baxter State Park, it would protect critical wildlife habitat and offer diverse recreational opportunities, including some hunting and snowmobiling to meet local preferences. Another proposal calls for expanding Canyonlands National Park in southeastern Utah by extending the park boundaries to the geologic basin’s rim in order to protect ecological resources from energy development and the indiscriminate use of off-road vehicles. An alternate proposal would designate a much larger Bears Ears National Monument to be jointly managed by federal and tribal officials. Both proposed designations would facilitate landscape-level conservation of the area’s invaluable natural and cultural resources. Yet another proposal calls for expansion of Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area just outside Los Angeles to protect critical habitat for several species and to provide additional outdoor recreational opportunities for this diverse community’s urban dwellers. Park expansion and protection proposals have also been advanced at Grand Canyon, Mojave, and elsewhere, each designed to afford similar landscape-level benefits while also protecting cultural heritage values.

Whenever such new park proposals are advanced, one political refrain often heard in opposition is the need to maintain the areas that we already have given the current maintenance backlog. This argument, however, presents a false choice, propounded principally by opponents of any new federal land acquisitions or any new federally protected areas. Historically, new park designations have not noticeably impacted the National Park Service budget, except when congressional opponents have withheld funds to manage the new area, as first occurred following Yellowstone’s designation and, more recently, following the 1994 California desert protection legislation. The harsh reality, given present municipal expansion and energy development patterns, is that undisturbed lands are disappearing at the rate of 1.6 million acres annually and climate change is altering natural systems. Unless we take deliberate action to preserve critical landscapes, future generations will not enjoy the natural world that is such a vital part of our American heritage and so essential to our future well-being. No shortage of payment options exist—an outdoor equipment tax, graduated entrance fees, an income tax check off, mineral royalty funds—to cover the modest price (in terms of the overall federal budget) for pursuing a farsighted conservation agenda that includes new parks and protected areas.

If we are to have additional national parks as part of the centennial or in its aftermath, then we must make a compelling case for them and secure necessary public support. Park designation decisions, as Mather so clearly understood, are inherently political in nature, so the case must be made in politically appealing terms and in a political setting. There are important stories not presently represented in the national park system, and ever more pressing reasons to protect our dwindling natural and cultural heritage at a landscape level. The National Park Service stands alone among the federal land management agencies in terms of its historic preservation experience and educational capacity. It has a proven record of safeguarding the lands entrusted to it and engaging the public in these special places. It is therefore time, in the spirit of Stephen Mather, for the Park Service and its constituencies to frame a compelling system-wide vision for new park proposals and to cultivate the political support necessary to bring this vision to fruition. The national park system, after all, is intended to benefit both present and future generations.

Robert Keiter is the Wallace Stegner Professor of Law, University Distinguished Professor, and founding Director of the Wallace Stegner Center for Land, Resources and the Environment at the University of Utah S.J. Quinney College of Law, Salt Lake City, UT 84112; [email protected]., and the author of To Conserve Unimpaired: The Evolution of the National Park Idea (2013).

My sincere thanks to Deny Galvin for his thoughtful comments on an earlier draft of this essay. -- Robert Keiter

Comments

Um...., Pinnacles National Park, San Gabriel Mountains National Monument, Sand to Snow National Monument, Mojave Trails National Monument, Castle Moutains National Monument, all within the past 5 years, all within California.

Do these not count because they were all done by executive order rather than Congress (or in the case of Pinnacles, Congress converted the monument to a park)?

Pinnacles NP was already in the system, dating to 1908, and is just 26,606 acres. San Gabriel Mountains NM is Forest Service, Mojave Trails is BLM, as is Sand to Snow.

Castle Mountains NM is NPS, but at just 21,000 acres, not sure it truly qualifies as "significant acreage" in terms of a national park. Valles Caldera is nearly five times as large.

The Maine North Woods proposal, meanwhile, is roughly the same size as Valles Caldera.

Most people assume that national monuments proclaimed by the president under the Antiquities Act are administered by the National Park Service. For many decades, this was generally true. It is not true for most monument lands designated in recent years.

Since the California Desert Act in 1994, almost 10 million acres of public lands have been designated by three presidents as national monuments. Only about 5 percent of the new monument lands were placed under National Park Service administration. Of these lands, over 80 percent were within the expansion of one area -- Craters of the Moon National Monument.

During this time, 85 percent of the new monument lands have been left under the administration of the Bureau of Land Management. Almost 8 percent of these lands have been left under U.S. Forest Service administration. This, despite the fact that neither agency has the mandate, resources, or expertise to provide management that reaches National Park Service standards.

The Antiquities Act has also been used by these presidents to designate about 745,000 square miles of marine national monuments. None of the monuments have been placed under National Park Service administration. Instead, they are jointly managed by the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.