Seismic lines laid across Big Cypress National Preserve in 2017 and 2018 remain highly visible in this aerial photo taken late in 2020/NPCA

Energy And Mineral Extraction

By Kurt Repanshek

What If Exploration Turns Into Development?

From the air, the seismic lines worm their way across the landscape of Big Cypress National Preserve, while underfoot some are hard-packed routes that thwart vegetation and alter the flow of the "river of grass." The impairment to the country's first national preserve, a wild remnant of what once covered southern Florida, is both palpable and tangible.

The lines were laid down in 2017 and 2018 by massive, 33,000-pound trucks that cruised through the preserve's backcountry, stopping again and again and again to, essentially, shake the earth to send seismic vibrations that could be used to identify pockets of oil below the marl prairie. Though it's not publicly known whether Burnett Oil Co. will send its trucks back out into Big Cypress to resume the search, the damage has been done.

"While the hunt for fossil fuels in Big Cypress has not been restarted since 2018, both the lasting impacts of the oil hunt and the looming threats of more to come still face our nation’s first national preserve," said Melissa Abdo, the Sun Coast regional director for the National Parks Conservation Association. "It is deeply troubling to see that, as of December 2020, so many of the previously pristine areas of Big Cypress, where industrial-grade seismic testing occurred in 2017 and 2018, remain in alarmingly poor condition.

"Where I used to see diverse native plant life, from grasspink ground orchids to butterfly-friendly milkweeds to old-growth dwarf cypress adorned with bromeliads, I often now see rutted seismic scars in their place," she added. "Some of these seismic-caused scars in the land are nearly devoid of any plant life at all, and most are now totally altered with a fraction of the diversity they once had, or worse yet have harmful invasive species establishing themselves. Sadly, these impacts are so serious that they are – even today – still visible from the air as cuts across Big Cypress’s landscape. It is untenable to ever permit this kind of damage from happening again inside Big Cypress."

A year go in Traveler's inaugural Threatened and Endangered Parks package Big Cypress was cited as very likely the park system's poster child for what constitutes an endangered park, and little if anything has changed. When Traveler visited the preserve in early March 2020 to examine the impact of the seismic testing, the damage was visible.

Walking through ankle-deep water across the marl prairie, passing rotund cypress domes and then hardwood hammocks with their leafy cocoplums, fronded sabal palms, live oaks, and other woody species, we were interrupted by the seismic scars. Twenty or more feet wide in places, they run roughly 100 miles across the preserve. Though the National Park Service when it issued Burnett Oil the necessary exploration permits ordered that "ruts, depressions, and vehicle tracks resulting from field operations will be restored to original contour conditions concurrent with daily operations using shovels and rakes to prevent the creation of new trails," that clearly hadn't happened everywhere.

This photo taken in March 2020 shows how some seismic lines greatly compacted soils and crushed vegetation/Kurt Repanshek file

"The Burnett Oil Company damaged the preserve by driving 'vibroseis' vehicles weighing as much as 33 tons—similar in weight to the M4 Sherman tank used in World War II—off-road through wetland ecosystems and endangered Florida panther habitat, in search of more oil," notes Alison Kelly of the Natural Resources Defense Council. "The National Park Service and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection assert that the oil company has completed its effort to fix the damage.

"Our scientific findings tell a different story. A new report written by our Florida-based environmental consultants reveals continued bias in the oil company’s reporting methods. For example, the 33-ton vibroseis vehicles left behind tire tracks almost two feet deep in places," she added. "But the oil company doesn’t focus its monitoring on the tire tracks. Rather, it focuses on the areas between the vibroseis vehicle tire tracks where the undercarriage of the vibroseis vehicle passed through wetlands, instead of studying the full extent of the damage."

In its mid-December report, in which Quest ecology compared its on-the-ground findings to those of Turrell, Hall and Associates, Inc., which was hired by Burnett Oil, Quest concluded that "it is reasonable to assume that long‐term soil, hydrologic, and vegetation damage will persist as a result of Burnett Oil Company’s seismic survey activities and unsuccessful reclamation attempts to date."

Lurking On The Fringes

Across the National Park System, there are a dozen units with producing oil and gas wells, according to NPCA, and another 30 where there are "split estates," in which the mineral rights are privately owned and could one day be developed, in theory. But the exploration doesn't need to be done within a park's boundaries to have an impact.

In New Mexico, lands around Chaco Culture National Monument long have been eyed for energy exploration and possible development. That possibility was put off at least a year when Congress in late December passed an omnibus spending bill.

It was back in 2014 when the U.S. Bureau of Land Management began to consider opening lands near Chaco Culture for oil and gas leasing. In 2018 the agency dropped the plan, with then-Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke saying there was a need for more consultation with tribes to understand their concerns over how the sale could impact cultural sites.

Come forward to 2020 and the BLM was planning to grant as many as 3,100 oil and gas leases in the area. Cultural groups, archaeologists, and environment and conservation groups protested that proposal, citing the spiritual nature of the park and surrounding lands, as well as possible damage to ruins. The Navajo Nation has been highly critical of the proposal.

The omnibus bill contained a provision that blocks the BLM from processing any oil and gas permits for tracts within ten miles of Chaco Culture until "a comprehensive ethnographic study and cultural resources inventory is completed," explained Ernie Atencio, NPCA's Southwest regional director.

While the House Natural Resources Committee in the last Congess passed the Chaco Cultural Heritage Area Protection Act to withdraw federal lands around the monument from energy extraction, the measure never gained full Congressional passage. Co-sponsoring the bill was U.S. Rep. Deb Haaland, D-New Mexico, who is President-elect Biden's choice to lead the Interior Department.

Chaco once was the heart of a sprawling complex. The area continues to hold great cultural and spiritual significance/NPS

“Protecting Chaco is part of who we are as New Mexicans,” Rep. Haaland said last summer when the measure was passed by the committee. “However, there are serious threats to our efforts from the oil and gas industry and my colleagues who benefit from those industries on the other side of the aisle. Some things are more important than money."

Though the San Juan Basin in which the national monument is located is known to contain fossil fuels, the region also is held in high regard by native cultures.

"While the footprint of Chaco Culture National Historical Park itself is small, the larger connected cultural landscape is vast. For Native peoples, the boundaries of the park do not encompass all that is important spiritually and culturally," said Emily Wolf, NPCA's New Mexico program coordinator. "The oil and gas industry has already heavily developed the region’s checkerboard of private, state, federal and tribal lands. Such development has scarred the landscape with tens of thousands of oil and gas wells and roads that now cut through the Chaco landscape, trafficked by trucks and heavy equipment, which destroy and endanger numerous ancient archeological sites, as well as sacred sites still used by Pueblo descendants and local Navajo communities.

"This only makes it more important that federal lands in the region be protected for their cultural values, not opened to even more drilling."

A Breath Of Clean Air

The energy deposits thought buried beneath the lands surrounding Dinosaur frequently come up in the U.S. Bureau of Land Management's oil and gas leasing plans. Near the end of President George W. Bush's second term, his administration proposed more than 350,000 BLM acres, split into 77 parcels, for oil and gas leases, including some surrounding Arches and Canyonlands national parks and near Dinosaur.

While the leases near Dinosaur were pulled back, the Trump administration tried to put them back into play. But last month a federal judge overturned the plan to lease more than 60,000 acres of public land for fracking in northern Utah’s Uintah Basin, including areas near Dinosaur, ruling that the BLM failed to consider alternatives to leasing all 59 parcels.

“Developing this landscape surrounding Dinosaur National Monument for oil and gas would degrade local air quality, both within the park and nearby communities, as well as threaten the park’s dark night skies, exceptional views and fragile habitat,” said Cory MacNulty, Southwest associate director for the National Parks Conservation Association. “We are heartened to see that BLM is being held accountable to comply with the law -- as it should have done from the start.”

There are concerns more fracking on the doorstep to Dinosaur National Monument could impair the air quality over Steamboat Rock and other parts of the monument/Kurt Repanshek file

The incoming Biden administration is not expected to challenge the ruling, but another administration down the road could revisit the leasing options.

“This is a strong rebuke of Trump’s disastrous fracking frenzy across our public lands, which is destroying the climate, wildlife and frontline communities,” said Taylor McKinnon, a senior campaigner at the Center for Biological Diversity. “President-elect Biden’s ban on new federal fossil fuel leasing can’t come soon enough.”

Mining Access

While the Trump administration ended 2020 by putting up a significant roadblock to the Pebble Mine in Alaska by refusing to issue a crucial water quality permit, which was good news for Lake Clark National Park and Preserve and Katmai National Park and Preserve, a road needed to provide access to the Mining District Industrial Access Project is proposed to cross about 20 miles of Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve in the state.

Though a lawsuit filed last summer seeks to halt the Ambler Road project, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act requires that right-of-way access be permitted across Park Service lands for this project. However, the plaintiffs allege that guidelines set down by ANILCA for such projects were not adhered to.

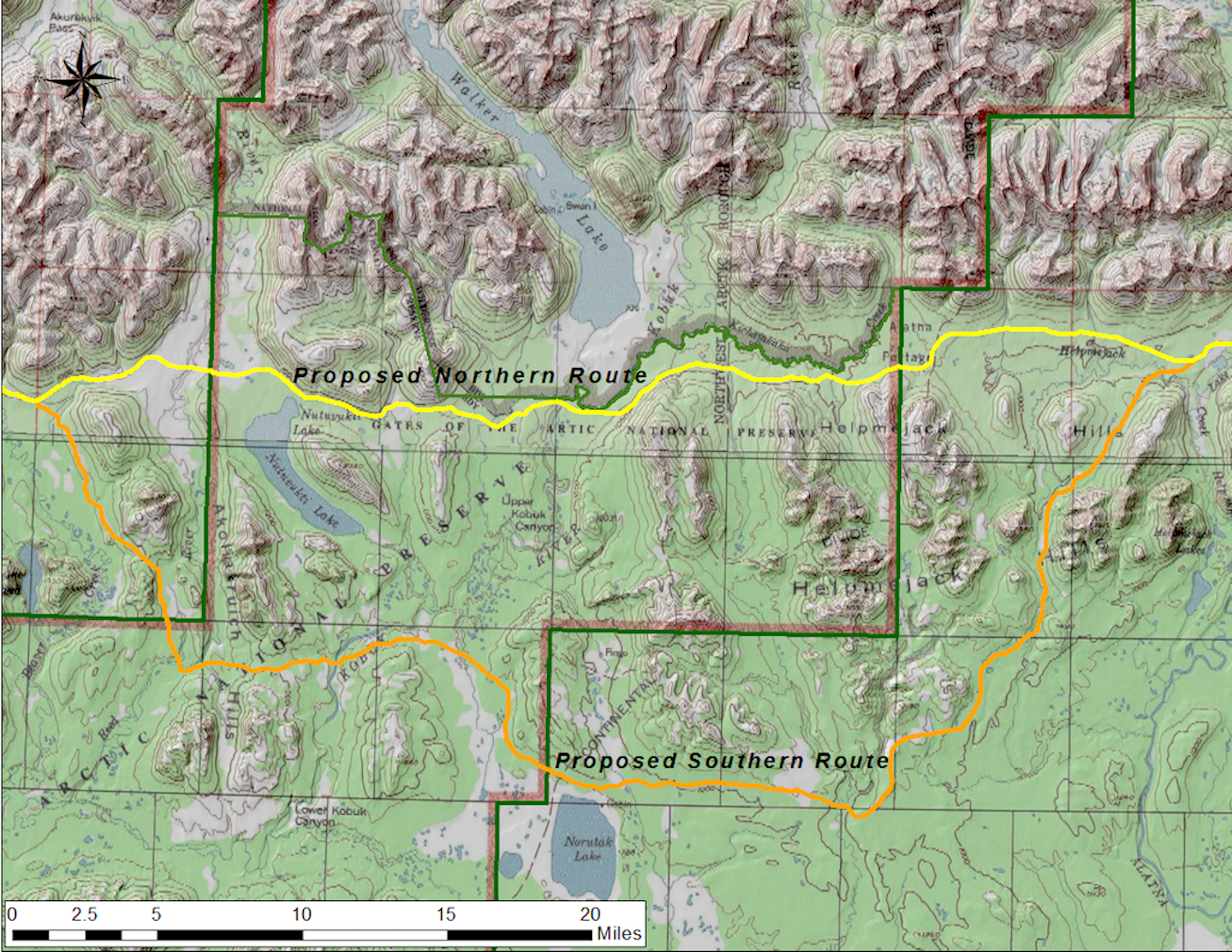

The Ambler Road as proposed would cut across about 20 miles of Gates of Arctic National Preserve/NPS

The Ambler Road as proposed would cut across about 20 miles of Gates of Arctic National Preserve/NPSThe lawsuit also notes that under Section 206 of ANILCA, all Park Service lands in Alaska created by the act were withdrawn from "all forms of appropriation or disposal under the public land laws, including location, entry, and patent under the United States mining laws, disposition under the mineral leasing laws."

Endangered Parks:

Big Cypress National Preserve, Florida

Threatened Parks:

Chaco Culture National Historical Park, New Mexico

Dinosaur National Monument, Utah/Colorado

Add comment