The Florida Wildlife Corridor is an ambitious proposal that, in theory, could link natural areas like St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge (above) to Everglades National Park/Erika Zambello

Surrounded by waving reeds, visitors and locals stand on the sand at St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, staring out across the Gulf of Mexico. Low tide has exposed a tiny beach in the midst of the grand salt marsh, hosting spectacular birding opportunities in the Florida Panhandle. An American Flamingo spends its winters here. American alligators slip silently through its shallow waters. Roseate Spoonbills and Great Egrets and Tricolored Herons probe the mud and flats for food.

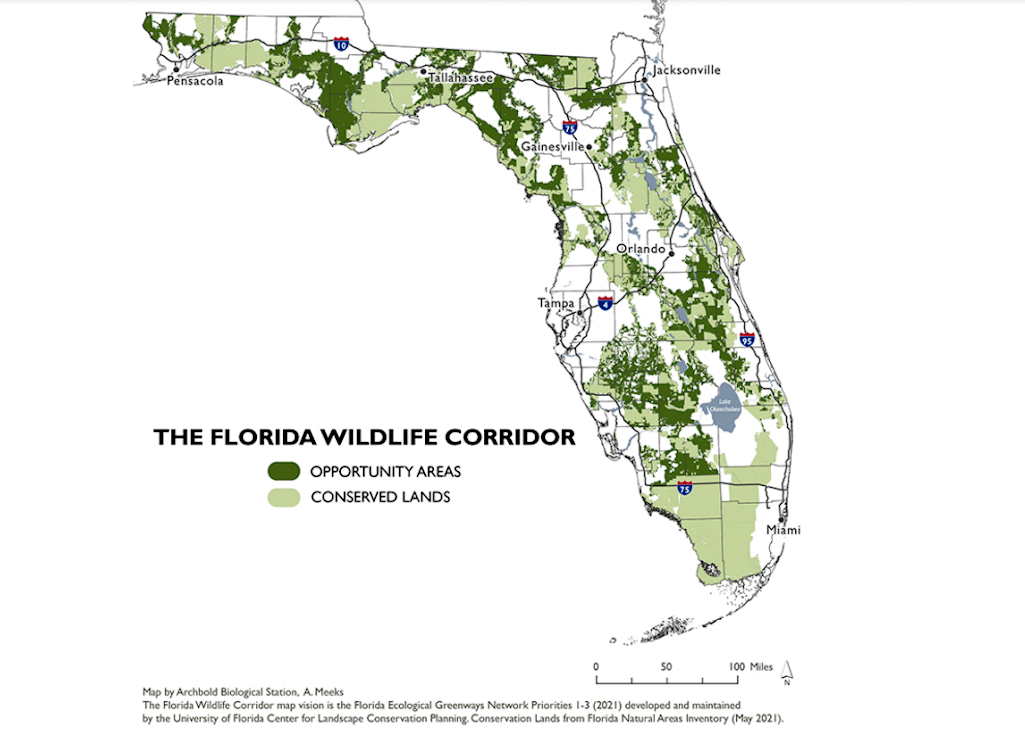

More than 400 miles away, similar species thrive in Everglades National Park. With the passage of a state law that strengthens the Florida Forever program, both sites could one day be linked by the Florida Wildlife Corridor, an aspirational 18-million-acre swath that would provide critical natural area connections for thousands of native species. So far, 10.1 million acres of the total have some sort of conservation protection.

Florida Forever is the state’s premier land conservation program, designed to acquire parks and preserves to provide recreational opportunities, habitat for imperiled wildlife, and other benefits such as water recharge and carbon sequestration. The Florida Wildlife Corridor is an ambitious conservation goal, aiming to create and connect natural area passages across the state, from north to south and also east to west. With new direction from Senate Bill 976 and federal COVID-19 relief, funding set aside for the Florida Forever Program could be used towards acquisition of parcels within the Florida Wildlife Corridor. Importantly, this program brings private landowners into conservation by incentivizing permanent easements on their property.

Millions of acres are ranches and timberlands: Nearly half of the 17.9 million acres of the Florida Wildlife Corridor are composed of working lands. There are 3.1 million acres of ranchland (18%) and 3.8 million acres of timberland (22%) within the Corridor serving as habitat and connection for wildlife. Of the combined acreage of ranchland and timberland, roughly 13% is currently protected.--Florida Wildlife Corridor

Using Florida Forever’s tried and true process for acquiring parcels (including checks for water quality benefits, habitat, cultural values, and public input), the state can begin to prioritize for purchase 95 parcels already identified in the Florida Forever program that are part of the corridor.

“The Florida Forever Program is like a tree,” explains Beth Alvi, director of policy for Audubon Florida, “and multiple conservation programs are its leaves, including the Rural and Family Lands Protection Program, Florida Communities Trust, Florida Recreation Development Assistance Program, and now the Florida Wildlife Corridor.

“It makes good sense to start with land identified in both Florida Forever and the Florida Wildlife Corridor,” she continues. “We do not want to set up separate, competing processes when the goals for both programs have such important overlap.”

The corridor is not like one road, narrow and thin, but rather envisioned as large, interconnected conservation areas. Such linkages are important for species with big ranges, such as the Florida panther; for migratory species, including birds; but also for longer-term movements of both plants and animals as conditions alter as a result of a changing climate. Without the opportunities for species to move farther north, they may go locally extinct. In fact, some of Florida’s most iconic species, like the Roseate Spoonbill, have already been documented nesting father north as conditions become less favorable for fledging chicks in the southern end of the state. The more conservation areas available in Florida - and beyond - the better chance these species have to adapt to climate change and encroaching human development.

"A Florida Wildlife Corridor would be beneficial to many Florida species, including the Florida panther, Florida black bear, and gopher tortoise," said Jacklyn Lopez, Florida director for the Center of Biological Diversity. "It is still largely aspirational, but the state did just allocate funding for purchasing land or at least securing conservation easements. I’m not too in the know regarding how realistic securing all the land is. There’s a lot of land yet to be acquired. As far as how important farm/ranch/ag land is in helping species, it’s all relative. Farmland is better then sprawl."

Still, the legislation is not without controversy. Money in these programs can go towards mitigation banking on easements, which could spur wetland development. Mitigation banking in theory is simple; loss to wetlands and streams results from various development activities, and is compensated for through the preservation and restoration of wetlands in other areas so that there is no net loss (to or within) the ecosystem of that region. While the idea can work, its success depends on proper guidance and implementation of regulations so there is no net loss in acreage and function of wetlands.

“The Florida Wildlife Corridor would help ensure the future of the state’s wildlife and tourism-based economy, while simultaneously creating a more climate resilient future," said Melissa Abdo, the regional director of the National Parks Conservation Association's Sun Coast office. "Connecting these millions of acres of habitat would benefit thousands of native wildlife and plant species, restore freshwater flow to Florida’s estuaries, protect our iconic springs and conserve aquifers that supply more 90 percent of Floridians with clean drinking water.”

The $300 million commitment the state recently made to support the corridor could be a significant boost to conservation in a state facing multiple climate-change threats, as well as an ever-growing population. Environmental groups are continuing to pressure the state government to purchase the best lands, protecting natural resources for the benefit of wildlife and ecosystems. In the end, that will benefit Florida’s people, too.

Add comment