Retreat of the tidewater rivers of ice at Glacier Bay National and Preserve is a clear and easily viewed sign of climate change. Not as visually apparent is what is transpiring beneath the shimmering surface bay waters in this 3.3-million-acre swath of mountain and marine wilderness.

Within those waters, an arguably more dire climate-triggered impact than glacial retreat is underway: the decline of the ecological web that nourishes humpback whales that visitors hope to spot in the park.

The humpback whales are returning to Glacier Bay. The last two summers saw a rebound in calves, to 12 and 11 calves, in and around the bay – up from zero in 2016. That was the low calving point of a multiyear marine heatwave that saw the area’s humpback numbers sharply decline, by well over half.

But that doesn’t mean the whales are out of trouble.

The 2014-16 marine heatwave did ebb, after near-surface water temperatures had risen more than 2 degrees Celsius above normal. That warming had contrasted with a Gulf of Alaska increase of 0.1 to 0.2 degrees Celsius per decade in the last half-century.

But Glacier Bay waters, while cooling some, are still not back to the long-term “normal “ summer average of around 9 degrees Celsius, scientists note; and climate-change projections foresee more frequent and severe warming events down the road.

And that is not good news for the food web that supports the whales. The whales’ diet of small schooling fish and krill took a beating in the heatwave years and has not fully recovered.

“It’s not the actual temperature that is the biggest problem for the whales. The heat is a proxy for what’s going on in the microbial portion of the food web,” said Seth Danielson, associate professor of physical oceanography at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Just as the Alaskan environment overall remains in the clutches of a warming trend that is unquestionably altering its natural attributes, so, too, are the whales still struggling.

Christine Gabriele is a National Park Service research biologist working with the program that has monitored humpbacks in Glacier Bay since 1985.

“During the heat wave we were seeing whales that were so thin that you could see their shoulder blades,” by the end of the summer feeding season, she said. “We see less of that now, but there are still whales that look thin at the end of the summer. Especially the lactating mothers.”

Yes, the whales are again reproducing, but the good news is tempered.

“They are still vulnerable, absolutely,” Gabriele said.

In Glacier Bay, park biologists identify individual humpbacks by their tail flukes and dorsal fin characteristics. Many live into their 60s and beyond, their ages ascertained by measuring growth rings in the plug of wax in whales’ ears. With its long-running program monitoring humpback behavior, the park has been able to limit boat speeds and locations to protect the whales.

“You see a whale for 30 or 40 years,” Gabriele said. “Whales come back year after year to the same place."

But many did not come back during the 2014-2016 marine heatwave and the years that immediately followed.

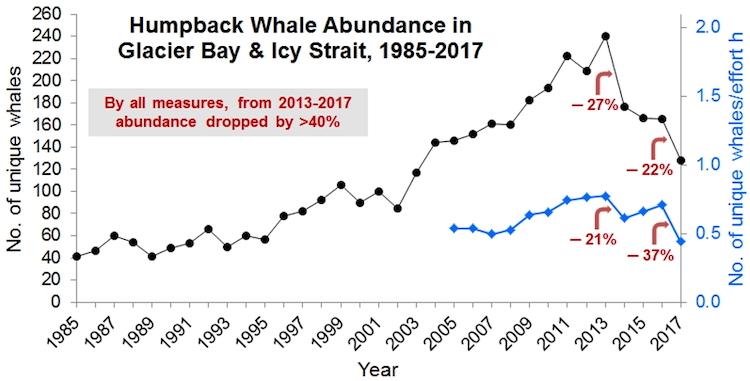

While stressor events often affect the oldest and youngest whales, this recent decline affected all age groups, including many in the prime of their lives and reproductive years, scientists say. The park’s annual Glacier Bay-Icy Strait whale count found that juvenile and adult humpback numbers peaked at 241 in 2013, and the following year began a slide to a low of 101 in 2018.

The number of humpback individuals climbed back to 167 this year, an improvement but far from a full recovery, the tally shows.

That’s because poor conditions continued even after the heatwave. “It was years after, and the whale population still was not able to recover,” Gabriele said.

“Through 2019 we were seeing low numbers in calving” and in calf survival, she said. From 2015 through 2019, about one calf was born for every 25 adult females, compared to one calf per three females prior to the marine heatwave.

For their annual humpback counts, scientists use an algorithmic tracking program to share identifying imagery of whale flukes that allows Glacier Bay researchers to confirm that their usual returnees have not been seen elsewhere in the world.

“Unfortunately, it was a big mortality event,” Gabriele said.

Despite improved numbers for the past two summers, the emaciated condition of some whales indicates the marine ecosystem has yet to recover. Scientists peg the decline in quality and quality of the whales’ marine prey as the root cause.

“Likely this was a cascading trickle-down effect. Those zooplankton and forage fish were similarly having a tough time finding enough to eat,” Danielson said, due to the combination of warming seas and increased glacier melt that created a marine environment in which the base-level phytoplankton were smaller, leading to a less efficient transfer of nutrients up the food chain.

In warmer waters, “We are increasing the length of the food chain and losing energy for feeding whales in the process,” he added.

A September report by Gabriele and her colleagues anticipated that continuing warming waters “may further destabilize prey resources vital to this population and many other marine species.”

That means it’s not only the humpbacks. Starvation also has been pegged as the likely cause of die-offs of several species of Alaska seabirds that have fish-based diets. Massive die-offs continued this year, with dead and dying seabirds reported from May to September in the Bering Strait region, Aleutian Islands and Gulf of Alaska, the National Park Service said.

“It may take years for the population to recover,” said the September report.

For park scientists, the years of documenting whales, glaciers and other natural attributes provides insights on the depth of what’s happening in a warming-buffeted ecosystem and a record that can inform the future.

“It helps to be able to quantify, even if individual parks can do little about climate change on a global scale,” said Gabriele.

Add comment