As the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem gets more crowded, groups like the Greater Yellowstone Coalition work to maintain corridors for migrating wildlife/NPS file, Jacob W. Frank

Don’t Fence Me In: The Greater Yellowstone Coalition Helps Animals On The Move

By Patrick Cone

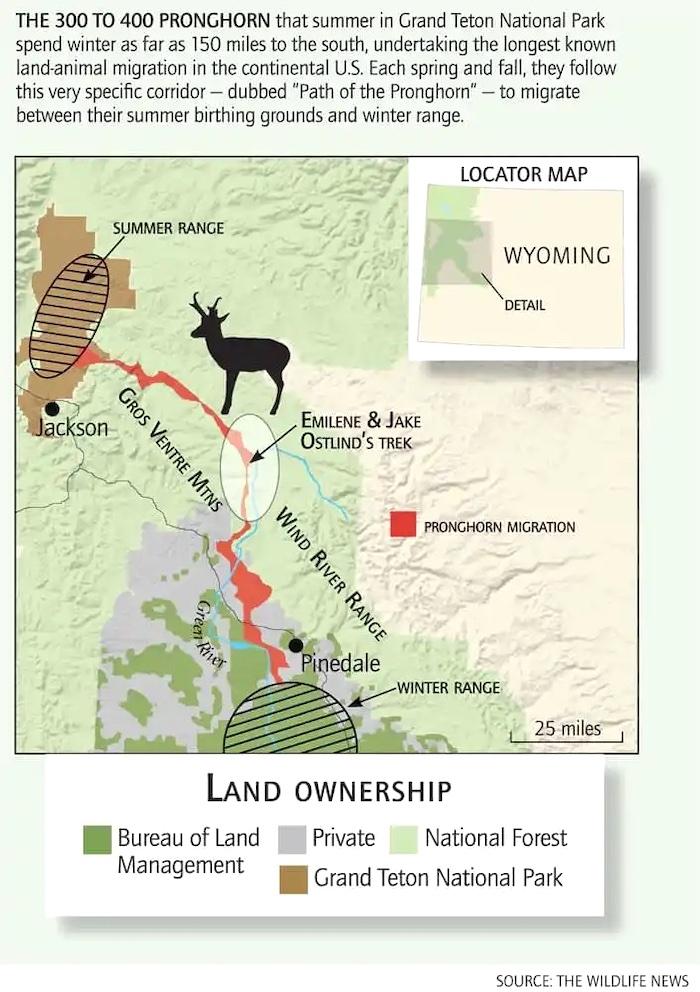

Animals don’t recognize city limits, county lines, or state boundaries. For thousands of years elk, deer, moose, bear, bighorn sheep, antelope and other wildlife have roamed the West in specific migratory patterns. But in today’s modern world there are barriers to these ingrained habits. Luckily there are lots of dedicated organizations, such as the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, helping to break down or modify those barriers so these animals can do what they always have done.

Celebrating its 40th anniversary this year, the Coalition's work in the sprawling ecosystem that contains Grand Teton and Yellowstone national parks, is more vital than ever, and increasingly effective. Collaborating with nearly three dozen other groups, as well as local, county, state, and federal officials, the nonprofit organization works to protect the natural resources across an incredibly large and rugged landscape.

“We work in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming, on the 20 million acres that surrounds Teton and Yellowstone national parks,” says Christi Weber, their director of communications and marketing. “We help various animals both inside and outside of the parks. We do that by preventing wildlife conflicts, working with landowners, building social tolerance for animals moving, whether it’s grizzly bears or migrating elk. It’s important for us to preserve the wildlife corridors.”

A wildlife underpass being built along US 189 near Labarge will help reduce wildlife-vehicle collisions/Patrick Cone

As strides are being made to protect 30 percent of the country's lands and waters by 2030, the need to protect migratory corridors has taken heightened importance. Back in the spring the White House's Council for Environmental Quality directed all federal agencies to outline how they can develop or restore and protect ecological corridors, including those relied upon by wildlife during their migrations. More specifically, the directive was for the agencies to maintain migratory corridors by "developing policies, through regulations, guidance, or other means, to consider how to conserve, enhance, protect, and restore corridors and connectivity during planning and decision-making, and to encourage collaborative processes across management and ownership boundaries."

The fragmentation of such corridors and the fraying of ecological habitats have greatly impacted wildlife. The 2022 State of the Birds report pointed out that more than half of bird species normally found in habitats as diverse as forests, deserts, and oceans in the United States are in decline. Climate change is a major factor in those declines, but human development also plays a key role by chewing into wildlife habitat and creating biological islands. The Pew Charitable Trusts last October released a report on the need for creating migratory corridors, and the challenges standing in their way.

Without well-defined and protected corridors, the large landscape national parks that are home to many species of wildlife will turn into biological islands as development hems them in.

There are three main threats to animals on the move: residential development, fences, and roads. In the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, ranchettes, subdivisions and trophy ranches can be barriers to migratory corridors. Local zoning, incentive programs, and education can help mitigate the impacts, but while everyone seems to like watching the herds of elk and bison, the thrill quickly fades when they’re eating the pricey landscaping.

While deer, elk, moose, bear and bighorns spend their summers in the high country, they need to move down from the snowy peaks to a winter range, which often is on a working ranch or private property. While some ranchers are glad to see them, there are economic impacts, like broken fences and damaged haystacks. But now there seems to be a solution. Local and national funding is paying landowners to host these animals. These elk occupancy agreements work, says Craig Benjamin, the Coalition's conservation director.

“We work with ranchers to get some subsidy to let elk on their property. Long-term, we want agencies to partner,” he explains.

And there’s more and more funding for these agreements. “Just last October the U.S. Agriculture Department and State of Wyoming formed a partnership for funding conservation habitat on private land,” says Benjamin.

This wildlife crossing near Bondurant, Wyoming, is intended to reduce the loss of mule deer to vehicle collisions/Patrick Cone

And just a few weeks ago the federal government announced a new $40 million partnership to expand the program into Idaho and Montana.

“Innovative solutions keep people and wildlife safe,” Benjamin adds, pointing out that even state conservation license plates add to the funds.

Another way to reduce conflict is by creating wildlife crossings, safe ways for animals to avoid becoming roadkill. And they do work. Along Wyoming’s section of Highway 189 near Big Piney, an average of 124 wildlife-vehicle collisions involving deer, moose, and pronghorn are documented annually, according to Weber. She says, “It is estimated that 3,000 mule deer, 300 to 500 pronghorn, 100 to 150 elk, and 50 to 100 moose cross this section of road annually. But now, with eight underpasses and fences which funnel animals towards them, there are far fewer killed."

Benjamin added that the "crossings, tunnels, bridges and fences reduce collisions by 90 percent.” And in 2019, a Teton County, Wyoming, approved a $10 million bond, which the Coalition worked to get on the ballot, to help pay for construction of crossings right now.

The Coalition, which receives financial support from Wild Tribute, the national parks apparel company, through its 4 The Parks campaign, in which they donate 4 percent of their proceeds to park projects around the country, also has worked on an advisory committee that has explored solutions to help moose safely cross roads in Teton County.

Twice a year pronghorn embark on long migrations that brings them at risk of being hit by vehicles on US 189/Greater Yellowstone Coalition

Beside these ungulates, of course, there are apex predators on the move too: wolves and bears, a touchy subject in the West. But they need room to roam too, and hopefully without impacting private landowners too much. The Ruby Valley Strategic Alliance is one example of a group working with a bunch of ranchers to create space for grizzly bears to move through.

"Landowners want for the most part to let these animals move through their land," says Benjamin.

But grizzly bears can become problematic for landowners and their cattle, sheep, and horses. To that end, GYC actually has employed a number of range riders to monitor conflicts and impacts. Their job is to ride the range on horseback, keeping their eyes on the ground for potential conflicts. Just like the old days.

As for wolves, “We understand that wolves are on the landscape, and that they belong on the landscape. We have to understand that people and livelihoods are just as important, too,” says Weber.

These predators follow these migrating ungulates, of course, wherever they roam. As for grizzly bears, “We do need to make sure grizzlies can move between and Crown of the Continent [around Glacier National Park in Montana] and Yellowstone,” says Benjamin. “We need to make sure grizzlies reduce confrontation, by helping people coexist with bears on the landscape. That prevents conflicts and reduces predation.”

The third way to keep migratory routes open is by addressing the number of fences. Barbed wire fences often injure, and even kill, ungulates trying to scale them. Fences, like roads, act as barriers to migratory corridors.

“The West is crisscrossed with fences,” says Benjamin. “They cause a lot of problems. Animals get tangled and they cut off migrations.”

Damaged fences cost ranchers a lot to fix, and cattle can run free through a broken fence. To address the problem, if fences can’t be removed they are sometimes modified with barbless wire, hung with flagging to make them more visible, the number of wire strands are reduced, or sometimes fences are even relocated.

It's taken decades for the efforts of landowners, officials and conservation organizations to come together to work collaboratively, to protect the West’s wildlife that they all love. A West without wildlife would be a sad place.

“Conservation is collaboration,” adds Weber, “working with people and everyone. In new conservation it’s better to work together.”

This article is made possible in part with support from Wild Tribute.

Add comment