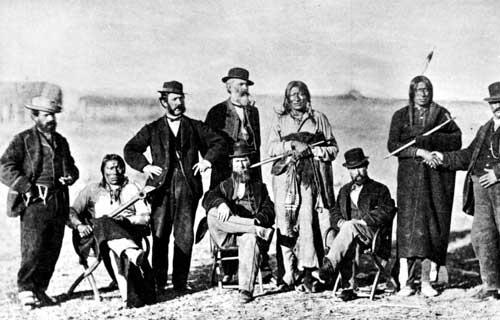

Indians and whites at Fort Laramie in 1868/From a photograph by Alexander Gardner in the Newberry Library.

A treaty negotiated more than 150 years ago between the Standing Rock and Oglala Sioux tribes at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, needs to be reviewed and enforced, particularly the section that called for a "Great Sioux Reservation" for the two tribes for their "absolute and undisturbed use and occupation," say the tribes.

“For centuries, the U.S. government has broken every promise it’s made to Native tribes,” says Standing Rock Chairwoman Janet Alkire. “It’s time for that to stop. Furthermore, we’re calling on the Biden-Harris administration to take active steps to correct the record.”

In a release the tribes said the treaty negotiated in 1868 also contains language the Sioux chief signatories never agreed upon: “[A]nd henceforth [the Sioux] will and do hereby relinquish all claims or right in and to any portion of the United States or Territories, except such as is embraced within the limits [of the Great Sioux Reservation] aforesaid.”

Today, this “relinquishment” language refers to roughly 48 million acres of land formerly comprising the Great Sioux Reservation, including the Black Hills. The Standing Rock and Oglala Sioux Tribes say the language was fraudulently added to the treaty by U.S. treaty commissioners after the chiefs signed the document.

“U.S. treaty negotiators snuck the relinquishment language into Article 2 of the treaty after it was signed by the Sioux chiefs to end the Powder River War,” said Oglala Sioux Tribe President Frank Star Comes Out. “We’d like the current government to take an honest look at what happened.”

The treaty played a role in subjugating the Northern Plains Indians, noted the late Richard West Sellars, who spent his career for the National Park Service as a historian and back in 2011 wrote a two-piece account for the Traveler on how the Park Service wasn't faithful to that history in its interpretation at today's Fort Laramie National Historic Site.

"Troops coming out of Fort Laramie participated in the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877, seeking to force non-treaty Indians onto their reservation, and fighting at Powder River, Rosebud Creek, and Slim Buttes," wrote Sellars.

The military also failed to "steadfastly defend treaty-guaranteed Indian land rights against white incursion," he pointed out. "Surely the most notorious failure was the aborted effort to protect Sioux tribal rights once the Black Hills gold rush began in 1874-1875. Willing to confront Indians almost anywhere on the plains, the army vacillated in blocking white access to the Hills."

Furthermore, Sellars noted that, "After the Indians had won decisively at Little Bighorn, but suffered defeat elsewhere, an official delegation from Washington coerced the Sioux into an 'agreement' giving up their rights to the Black Hills portion of their reservation—lands the 1868 treaty had guaranteed them. Threatening to withhold food rations, the delegation used a sign-or-starve ploy to force tribal acquiescence. Even without approval of three-quarters of the adult Indian males, as required for variances from the 1868 treaty, the government declared a new agreement had been reached.

"As a result, the Sioux lost a wide strip of their reservation along the entire westernmost border of today’s South Dakota, where an abundance of natural resources had already been discovered in the Black Hills. An 1877 Act of Congress confirmed the government takeover. The seizure of the Black Hills, in open contradiction to the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, is at the center of the decades-long Sioux legal efforts to gain satisfactory redress from the government—efforts that have never yet reached a conclusion," Sellars wrote.

That effort continues today.

“It is ironic that the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, the Hunkpapa and the Ihunktuwana (Cuthead Dakota), are joining forces with the Oglala Sioux Tribe, the tribe of Red Cloud and Crazy Horse, to hold Civil War General Lieutenant-General William T. Sherman, General William S. Harney, General Alfred H. Terry, and General C. C. Augur accountable 155 years after they fraudulently inserted the relinquishment language in the treaty and got the U.S. Senate to ratify the fraudulent language,” said Star Comes Out.

The tribes say their position is corroborated by findings of the Indian Claims Commission (ICC), which examined the history behind ICC Docket 74 and found that the Indian Peace Commission presented the proposed treaty to the Sioux bands at a series of councils held in the spring of 1868. At the councils, after hearing an explanation of the terms of the treaties, the Sioux generally agreed they had never been willing to cede any of their lands.

Nowhere in the history leading up to the treaty or in records of the negotiations is there any indication that the United States was seeking a land cession, nor is there any reason to believe that the Sioux were willing to consent to one, tribal officials say, the tribes' release said. "On the contrary, evidence from the 1978 ICC case Sioux Nation of Indians v. United States shows that the Sioux would never have signed the treaty had they thought they were ceding any land to the United States."

The Indian Claims Commission report concluded as follows: “The history of this case makes it clear that the treaty was an attempt by the United States to obtain peace on the best terms possible. Ironically, this document, promising harmonious relations, effectuated a vast cession of land contrary to the understanding and intent of the Sioux.”

The Standing Rock Sioux and Oglala Sioux Tribes are offering to jointly sponsor nation-to-nation consultations between U.S. Interior Secretary Debra Haaland, the Assistant Secretary of Interior for Indian Affairs, and the remaining 1851-1868 treaty signatory tribes.

“This is about correcting an injustice,” says Alkire. The Black Hills are not for sale, and they never were.”

Traveler postscript: You can find Richard West Sellars' articles here and here.