Guadalupe Mountains National Park is home to the world’s most extensive Permian fossil reef, the four highest points in Texas, various ecosystems, and historic stories of bloodshed and survival all waiting to be explored. From forested mountains and desert dunes, Guadalupe Mountains offer various ways to explore the area through hours of hiking and backpacking trails not for the faint of heart, or via beautiful settings of flora and wildlife within reach of families.

This national park is one of the most unique in the United States as it allows visitors to explore different environments within the underrated desert of West Texas.

Traveler's Choice For: Rugged backcountry exploration, photography, birding, history

Getting Around Guadalupe Mountains National Park

Guadalupe Mountains National Park is located in far West Texas and can be reached via U.S. Highway 62/180. The driving distance is 110 miles east of El Paso, Texas, 56 miles southwest of Carlsbad Caverns National Park, or 62 miles north of Van Horn, Texas on Highway 54.

Park History

Guadalupe Mountains National Park is much more than hiking trails in the Chihuahuan desert; it is a park with more than 10,000 years of human history.

The mid-19th century saw Mescalero Apaches fight to defend their lands in West Texas as settlers, cattle drivers, and stage lines began to claim it as their own. They were met with bloody conflict as the federal government sent thousands of soldiers west to drive them from the landscape.

Following the Civil War, African-American soldiers were sent west to control Indian hostilities on the Great Plains. It’s difficult to overlook the irony facing these soldiers, who had gained their freedom through the Civil War that nearly tore the country in half only to be sent into the West to deprive the Mescalero and other native peoples of theirs.

These soldiers, given the name “Buffalo Soldiers” by the Cheyenne for their dark skin, fought native cultures for more than two decades, and also contributed to the mapping of the region. By the late 1800s, the Mescaleros had been driven from the Guadalupe Mountains.

Mescalero Apache pictographs can be found in caves at Guadalupe Mountains National Park/NPS

After the Mescalero Apaches were driven out, many settlers attempted to make a living farming and ranching, however few were successful in the rugged and arid landscape.

Some exceptions were the Smith family, the Belche’s, and Adolphus Williams. They had discovered the secrets to making a hardscrabble living off the land, either running livestock or growing crops. The Smiths operated an orchard at the Frijole Ranch for almost 40 years, while the Belchers owned a ranch that eventually was purchased by Willliams.

These holdings were consolidated in the 1940s, when Judge J.C. Hunter bought both operations and eventually owned the majority of lands that would become the park. The judge loved the land, and figured it qualified for inclusion in the National Park System.

But piecing the lands together for a national park was not easy. First the National Park Service had to acquire the subsurface mineral rights, which it did when the state of Texas and the Texaco energy company agreed to donate their mineral interests to the Park Service. The judge’s son, J.C. Huner, in August 1966 offered to sell the family’s holdings to the National Park Service for $1.5 million, and gave the agency 18 months to close the deal.

To make a long story short, one that was complicated by Congress’s stinginess in providing funds to buy out Hunter, the Park Service was able to finalize the acquisition of 72,071 acres from Hunter in December 1969. That amounted to more than 90 percent of the eventual national park, and in the ensuing years the Park Service whittled away at acquiring the additional inholdings.

In October 1966 Congress authorized creation of Guadalupe Mountains National Park, and in September 1972 it was formally established.

From the violence between the Mescalero Apaches and Buffalo Soldiers to ultimately becoming a national park, Guadalupe Mountains is home to an abundance of natural and cultural history, some of which is preserved at the Frijole and Williams ranches and at the ruins of Pinery Station, a stage stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail Route that stretched from Tennessee to San Francisco.

Natural History

Along with its rugged beauty, the Guadalupe Mountains long provided valuable natural resources to native cultures and to 19th and early 20th century settlers. The Salt Flats, a mineral flat left behind by a shallow lake that existed nearly 2 million years ago during the Pleistocene Epoch, was a ready source of salt.

The salts were transported here by streams flowing out of the mountains, according to the National Park Service. In a geologic twist, the basin actually sank – it was a “graben,” a block of land that sank while the surrounding mountains, in this case the Guadalupe Mountains, rose. The result was a shallow basin that filled with water during the Pleistocene Epoch when rainfall was more frequent and plentiful than today.

This rich mineral resource came to be when the lake dried up, leaving behind the salt deposits that became a significant resource to people within the El Paso area and which would ultimately cause the El Paso Salt War.

Salt was a sacred and precious resource to native Apache and Tigua peoples. And it also was sought out by newcomers to the region. In 1692 an Apache prisoner led Diego de Vargas and a small company of Spanish soliders to the Guadalupe Mountains and these salt beds. That was the beginning of nearly 150 years of dependency on the salt by Spanish, Mexican, and early white settlers in the region.

Gypsum dunes in the Salt Basin of Guadalupe Mountains National Park/NPS

After the Mexican-American War ended in 1848, many Mexicans chose to stay in El Paso and relied on salt to supplement their incomes from farming. While running the risk of being attacked by Apache Indians, Mexicans and Mexican Americans traveled to the salt flats to make a living.

Up until the mid-1800s, these lands were not claimed and were available to those who made the trip there. But in the late 1860s three businessmen -- W.W. Mills, Albert J. Fountain, and Louis Cardis -- attempted to monopolize the salt flats and charge a fee on salt collection.

As this escalated, Mexicans became outraged because under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo the salt beds were considered to be public property. In 1877, riots erupted over the dispute. They were spurred by Charles Howard, a lawyer brought in to help Cardis and Mills control the salt beds.

On December 17, 1877, Howard, his agent John E. McBride, and John G. Atkinson, were fired on by Mexicans, further inciting the El Paso Salt War. Military troops and vigilantes responded, leading to the killing and wounding of many people. In the end, Mexicans were robbed, assaulted, murdered and ultimately charged to collect salt.

This short, but brutal warfare revealed the economic and political struggles to come to the area, and nearly jeopardized the peace after the Mexican-American War.

Wildlife at Guadalupe Mountains

From the hot Chihuahuan desert to the mountaintop forests of pine and fir and streamside woodlands filled with oaks and maples, the Guadalupe Mountains host a variety of diverse ecosystems.

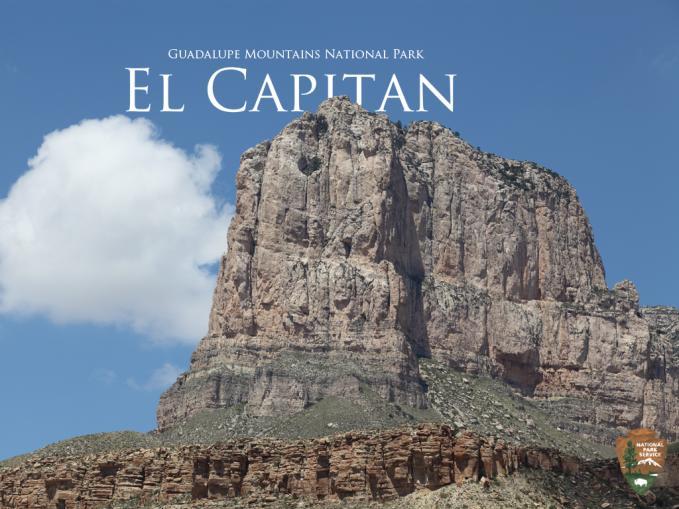

The park is also home to a mass of uplifted fossilized marine reef that stands as a mountain in western Texas. The world’s most extensive Permian reef was formed from the skeletal remains of flora and fauna that were compressed into what is known today as Capitan limestone. Its most formidable and best-known feature is the cliff known as El Capitan that rises 1,000 feet above the desert floor.

These ecosystems combined provide a home to 60 species of mammals, nearly 300 bird species, and 55 species of reptiles. However, animals are not often seen as much as one would expect due to the hot and dry conditions found across much of the park.

Stay out after dark, though, and you might just spot some of the animals that wait for the sun to go down before roaming the landscape. Rise early, before the day’s heat sets in, and you might spy some of the wildlife foraging for food and water. If going out in the dark doesn’t appeal to you, spend the daylight hours looking for tracks, scat, diggings, and nests that might tell you what passed by or lives here.

From time to time mule deer can be spotted throughout the park, especially near campgrounds or along park trails. On rare occasions encounters with mountain lions, a pack of javelinas, or even black bears can occur, but you’re not likely to come across any of these animals.

As the seasons change, different animals can be found by lucky visitors. For example, during the winter months elk, coyotes, gray fox, cottontails, jackrabbits and ringtails are more likely to be seen than during the hotter summer months

The warmer months offer many sightings of various lizards and snakes common to the desert ecosystem. They are more likely to be found during the day, but keep your distance to avoid the bite of a rattlesnake.

Though the national park is surrounded by high desert, there are lush areas to be found within its borders/NPS

Five different species of rattlesnakes reside within the Guadalupe Mountains, but typically reserve their venom for more suitable prey, unless provoked. According to National Park Service, rattlesnakes are the only venomous snakes found in the mountains, and can easily be identified by their flat, triangular heads.

Among the most unexpected and wonderful ecosystems in the park are the riparian areas, due to their beautiful water features – there are springs, seeps, and some streams – that attract, mule deer, skunks, and racoons. Long-ear sunfish can be found in some springs, including those in McKittrick Canyon.

Within the park there also are more than 1,000 plant species representing the Rocky Mountains, Great Plains, and Chihuahuan Desert ecosystems; as you change elevation in the park you’ll see that the vegetation changes, too. Cacti, desert succulents, ferns, grasses, wildflowers, shrubs, and trees of many kinds grow in the Guadalupe Mountains. Check the park’s website to find more details on the many plant species.

Hiking in Guadalupe Mountains

Guadalupe Mountains National Park covers 135 miles and is part of the ancient horseshoe-shaped Captain Reef that formed beneath a tropical ocean about 250 million years ago. Within this rugged and varied landscape you have more than 80 miles of marked trails, and countless miles of landscape to explore on foot.

The exposed reef that formed El Capitan tops out at an elevation of 8,078 feet, and one of the park’s more popular trails will lead you on an 11.3-mile roundtrip.

El Capitan is about 700 feet shorter than the nearby Guadalupe Peak, which is known as the highest point in Texas, rising 8,751 feet. It is the most popular hiking trail within the park and the payoff is a breathtaking view. The Guadalupe Peak Trail, otherwise known as the climb to the “top of Texas,” is an 8.5-mile round-trip hike. The intensive hike takes 6-8 hours and climbs 3,000 feet high.

Challenge yourself with a hike at Guadalupe Mountains National Park, such as along the McKittrick Trail/NPS

The park's McKittrick Canyon contains some surprising hardwoods in this "island in the desert." This is a popular destination, especially during the fall color season, so don't expect this remote location to provide an escape from crowds. The backcountry McKittrick Ridge Campground with its eight sites is 7.6 miles from the trailhead.

To see all of the park’s trails, click here.

Regardless of the trail you take, remember to bring plenty of water, sunscreen, and food to survive the desert heat.

Camping Guadalupe Mountains

After a day of hiking the trails of the Guadalupe Mountains, you can settle down in one of several campgrounds. The park offers group campsite reservations at the Pine Springs and Dog Canyon campgrounds. There is no lodging available inside the park.

These group campgrounds can be reserved up to 60 days in advance, and are the only ones designed to hold large numbers of people and so help minimize erosion or conflict with family or individual campers.

To reserve these areas, you must have a minimum of 10 campers, but no more than 20 in your group. There are no reservations available for individuals or smaller groups.

Group site fees are $3 per person per night, with a separate entrance free of $10 per person that lasts up to seven days.

There are individual campsites in Guadalupe Mountains National Park, such as this one at Pine Springs/NPS

If you’d like to reserve a group site, email [email protected] and put “Group Reservations” in the subject line. Include the following information;

● Group Name

● Contact Person, Phone Number/Alternate Phone Number and Email Address

● Which Group Site (Dog Canyon or Pine Springs) Note that Dog Canyon is 2 hours away from Pine Springs.

● # of People in Party

1. (A minimum of 10, maximum of 20 per group site)

2. Groups over 20 must obtain a Special Use Permit when visiting the park.

● Check In Date and Time (No more than 60 days in advance).

● Number of Nights

● Check Out Date

A park ranger will review your application and send you a confirmation or refusal letter. If the dates you'd like are booked, park staff can offer you alternative dates.

Please keep in mind the following concerning front-country campgrounds:

● There are no advance reservations for any of the individual sites in park campgrounds.

● Campgrounds offer potable water, a utility sink for dishwashing, and restrooms with flush toilets

● Open fires, including those fed by charcoal, are not allowed in any of the campgrounds. Canister-fed stoves are allowed.

● Generators are permitted in designated areas between 8 a.m.-8 p.m.

Traveler’s Checklist

1. Dog Canyon: A secluded forested canyon that sits at an elevation of 6,300 feet. This area offers quiet camping, birding, and hiking. Nearby trails include the Indian Meadow Nature Trail, Marcus Overlook, and Lost Peak. Check in at the ranger station for information and permits for backpacking and horseback riding.

2. McKittrick Canyon: This area offers beautiful fall foliage combined with the characteristics of the Chihuahuan Desert to enjoy the day. With unique historic and environmental elements, nearby trails include: McKittrick Canyon Nature Trail, Pratt Cabin, The Grotto, McKittrick Ridge, and Permian Reef Trail. Backpacking is also available with a permit from the headquarters Visitor Center.

3. Williams Ranch: Check out a gate key at the Pine Springs Visitor Center and explore the dirt roads on your 4X4, high ground clearance vehicle, and see the historic ranch.

4. Frijole Ranch: Visit the Frijole Ranch Museum and enjoy a relaxing day walking the Smith Spring and Manzanita Spring trails as you explore “desert paradise.”

5. Salt Basin Dunes: These desert lowlands showcase the variety of environments offered at the Guadalupe Mountains; from forested areas to this stark landscape, safely explore two different worlds.

6. Stargaze: More than 11,000 stars and the Milky Way are visible every clear night horizon-to-horizon.

7. Carlsbad Caverns National Park: The Guadalupe Mountains’ sister park is located in Carlsbad, New Mexico, where visitors can explore one of the world’s most unique cave system.

Guadalupe Mountains Weather

The weather can drastically change within the park. Summers typically feature warm temperatures with highs approaching the 90s and the chance for showers; fall brings wonderfully mild temperatures but with the chance of high winds; winter months can bring snow and freezing fog, though daily highs in the mid-50s are typical; spring offers comfortable temperatures for hiking and backpacking, along with the chance for showers.

For the latest weather updates check here, but keep in mind that higher elevations tend to be 7-10 degrees cooler than the park's floor. For example, Dog Canyon is at 6,000 feet in elevation and tends to be cooler than the Pine Springs area.

Come prepared with proper clothing, food and water and enjoy the Guadalupe Mountains National Park.