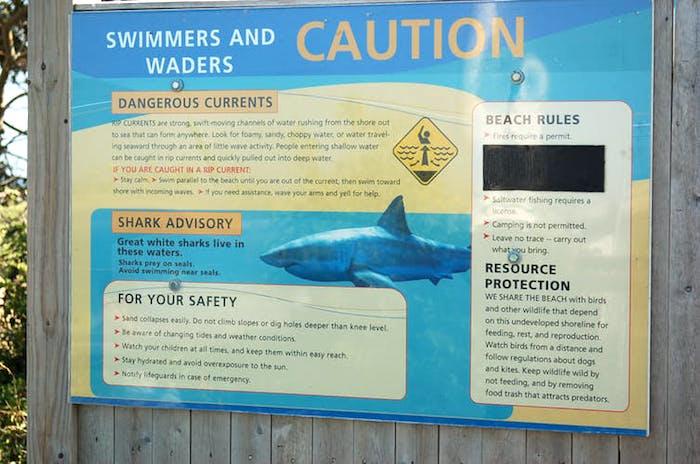

Warning sign at a Cape Cod beach/Carlos García-Quijano, CC BY-ND

Editor's note: This article, by Carlos G. García-Quijano, an Associate Professor of Anthropology and Marine Affairs, University of Rhode Island, is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Interactions between people and animals offer insights into human culture and societies’ core values. This is especially true with respect to large predators – perhaps due to a collective memory of our evolutionary past as hunted prey.

Along with fellow anthropologist John Poggie, I have been studying relationships between humans and white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) on Cape Cod since 2015. Atlantic white sharks have historically preyed on grey seals, but largely disappeared from Cape waters after hunting reduced local seal populations in the 19th century. After the Marine Mammal Protection Act was adopted in 1972, seals recovered in force, and white sharks have followed.

Since the mid-2000s, shark sightings in Massachusetts waters in summer and early fall have progressively increased. Until recently, the public response was largely positive. Our work with local stakeholders indicated an encouraging but delicate balance in the relationship between people and sharks.

But with more sharks appearing, risks increased. In 2012 a swimmer sustained moderate injuries from a white shark bite. Another swimmer was seriously injured by a shark on August 16, 2018. Then, on September 16, a 26-year-old bodyboarder was killed in what is believed to be the first fatal shark attack in Massachusetts since 1936.

We have been told often on Cape Cod that a fatal attack could change everything. Now the region faces a choice: Live with predators, or try once again to eliminate either sharks or their prey.

William Lytton, of Scarsdale, New York, suffered deep puncture wounds to his leg and torso after being attacked by a shark on Aug. 15, 2018 while swimming off a beach in Truro, Massachusetts. AP Photo/Steven Senne, File

A changing ecosystem and economy

Cape Cod is an extremely popular warm-weather destination that is highly dependent on beach tourism. Its year-round population of about 215,000 swells to over 500,000 in summer.

According to a 2012 study led by Massachusetts state shark biologist Greg Skomal, white sharks are repeat seasonal visitors to Cape Cod waters, and new white shark individuals continue to be recruited to the region every year. Anecdotal evidence supports this pattern, with shark sightings and beach closures increasing around the Cape. Media reports have featured sharks killing seals just feet from a beach and taking striped bass off fishing lines.

Sharks are culturally salient for practically every human society that has come into contact with them. Part of this reflects the risk of attack. Fatal shark attacks in the Americas have been documented by archaeologists as far back as A.D 1000.

In a variety of coastal locations, including South Africa, Australia and California, beach tourism and water sports-dependent economies have developed in the presence of white sharks. On Cape Cod, however, the timing has been different. As grey seal populations dwindled by mid-20th century, white sharks “left” the area.

Meanwhile, the relationship between people and their local coastal environment shifted as the Cape transitioned from a fishing-dependent economy into a water tourism destination. Most tourism revenue for the entire year is earned in summer – precisely when sharks converge around Cape Cod to hunt seals.

As sightings increased around the Cape over the past decade, the Massachusetts state government and nongovernmental organizations such as the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy launched acoustic tagging and monitoring programs to understand shark behavior. They also conduct public outreach and education initiatives to help people understand, appreciate and respect sharks.

Embracing the return of white sharks

We have interviewed and surveyed more than 1,300 Cape Cod residents and visitors to document challenges and opportunities posed by the sharks’ growing presence. For example, while the risk of shark attack can negatively impact beach tourism, visitor interest in white sharks is also a potential source of revenue.

In previous research, I have found that the tourism industry can be highly responsive to people’s interest in charismatic wildlife. The Cape Cod town of Chatham has adopted white sharks as icons, branding itself as “the summer home of the great white.” In June 2015 Massachusetts enacted regulations restricting recreational and commercial activities around white sharks.

Shortly after the August 16 nonfatal attack, we conducted an online survey of 1,120 Cape Cod residents and visitors to assess beliefs, attitudes, values and knowledge about white sharks in local waters. Overall, nonresidents’ attitudes seemed to be driven by their general views of nature and sharks’ place in it. Residents tended more to draw on their experience of local issues and conditions, such as how their use of beaches and local waters had changed because of sharks. They also were more likely to refer to the return of seals as a driver of rising shark populations.

Other researchers have found that when people perceive the presence of large land predators as conveying both risks and benefits, they are more likely to tolerate those predators near places of human activity. In our survey, respondents strongly agreed that white sharks had great potential to attract tourism revenue and raise environmental awareness. However, there was less agreement about how much inherent risk from sharks was acceptable. Residents were more likely to be concerned about the growing potential for shark attacks to harm tourism, fishing and their own enjoyment of water activities.

Respondents almost universally opposed lethal control measures. However, some residents strongly supported seal culls, and a number of them called the Marine Mammal Protection Act an unwanted intrusion into local affairs. In their view, the law had caused overpopulation that threatened fisheries and human safety, both via direct conflict with seals and by attracting sharks.

Massachusetts state marine biologist Greg Skomal explains how little is known about white shark populations along the East Coast.

A decision point

Since the fatal September 16 attack, one local politician has endorsed culling both sharks and seals. Biologists call culling ineffective and assert that tagging sharks is providing crucial scientific knowledge. Nonetheless, the attack has raised serious concern on and around Cape Cod, and is spurring discussion about the ethics of profiting from shark tourism.

As a precedent, Cape Cod officials and residents could look to Colorado, where cougars recolonized the area around Boulder in the 1990s.

As with sharks on Cape Cod, cougars were not purposefully reintroduced. Rather, measures protecting their habitat and food sources and restricting hunting made it possible for them to return to a new, human-dominated landscape, where leisure and outdoor recreation had largely replaced extractive resource uses such as logging and ranching. And Boulder residents had developed new sets of beliefs, attitudes and values about sharing space with large predators. After a high-profile fatal attack in 1997 and a contentious political process, Coloradans opted to forgo lethal control and focus on modifying human behavior near cougars.

Ultimately, in my view, the only activities that humans can manage and modify in a lasting way are our own. Social science can help communities strike a balance with nature by identifying acceptable trade-offs between the risks and benefits of coexistence. The return of white sharks to Cape Cod is just the latest example of the complex challenges, opportunities, and trade-offs posed by conservation in a time when humans have such broad influence over the natural world.

![]()

Carlos G. García-Quijano, Associate Professor of Anthropology and Marine Affairs, University of Rhode Island

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments

cull the seals & the sharks will leave again!! Leave it up to the individuals who live there!!

>CAPE'S EMERGING WILDLIFE RESERVE: Thanks to Pres. Kennedy and fellow Cape Cod enthusiasts, the Cape Cod National Seashore was created by the Federal government in 1961 to keep undeveloped areas on the Lower & Outer Cape from being broken into small private properties. The Upper & Mid Cape's interior land and shoreline had already been subdivided into small lots, with exclusive, privately-owned waterfronts.

Seals or sharks were not part of the Cape's habitat, and they would not be a menace today, if the government had listened to the concerns of fishermen, surfers, ORV drivers, and beachgoers. They have no plans to prevent these large animals from enlarging their territories, thereby reducing fish stocks and limiting human recreational activities. In fact, it appears that the National Seashore is now intentionally being turned into a National Wildlife Reserve, with less and less of the waterfront available for public access and recreational enjoyment. Furthermore, in recent years, roads, parking areas, campgrounds, bike trails and historic sites within the Seashore have consistently been underfunded.

Don't you know wild animals have more rights than humans according to the environmental science crowd! Let's see what happens when a politician.or family member dies.

I had to respond after reading the two previous comments. Jim says the government created an area for public recreation in 1961 instead of allowing only private ownership. Sounds good so far. But the government allowed the great white shark to expand its territory. So there were never sharks or seals in this area....say...a hundred, two hundred???? years ago?

Maybe the point of the comment is that the government should kill all dangerous wildlife in any area set aside for the public's use. I.e , Yellowstone National Park shouldn't allow Grizzlies, cougars, wolves or bison in the park. Why would millions of visitors travel there annually with such raw and savage danger present. I shall write my congressman about this reprehensible oversight! Although I'm willing to bet everything i own that in one week more people are killed travelling to Yellowstone than our killed in a century by animals in the park.

So, we want to listen to ORV users comments on managing wildlife and that of hunters and fishermen . I'm sure that someone who races around in a modern dune buggy, powered by a loud gas engine tearing up the fragile vegetation that takes hundreds of years to establish itself would have the environment as their foremost concern. And the hunter who doesn't want a predator to kill and eat (to survive) something the hunter wants to shoot.

Anyway, i digress. We want to commit genocide on a species that is responsible for one accidental death, (human mistaken for a seal) in a century for killing a swimmer in the ocean.

I can't imagine the carnival of horrors a previous commenter has planned for those who manufacturere autos , guns and tobacco products. Oh don't leave out the airline industry.

If the victim was a family member of mine, I would say, "I warned him (or her) about hanging out in the ocean ".

As a Canadian.....white sharks are off the coast of Nova Scotia.....we humans are land dwellers a sharks home is in the water...the ocean...when we enter there world...it's there home.....we are evading there territory..there home...how dare we threaten them just because they have to eat...its far time us humans stop thinking about ourselves and let our animals live in peace and co exist with us in nature...And stop crying about money and lost revenue....

Scott Spence

Montreal,Canada

Like a previous comment .we have no right to kill a shark as it's just doing its thing like it has for million of years .it's are stupid fault if we go into its domain .humans will only be happy when all animals have been wiped out .then they will wipe out themselves

If we kill the whites we kill the oceans. There are reasons the whites to keep the oceans ecology stable. Once the ocean dies so will we.

This is a reason these magnificent animals population must be retained. I know occasionally, man and animal will meet, sometimes tragically bbut we are in their HOME. And so we must learn how to live in their WORLD.

Nobody forces any individual to swim where these magnificent creatures swim, if you do so and you happened to meet one, you should be prepared to take the consequences, Sharks have been around alot longer than we have.