Jim Nimz of the National Park Service and Kris Moorehead with the WAVES Project map a submerged aggregate plant that was essential in making the huge volume of concrete it took to build Hoover Dam in the 1930s./Susanna Pershern, Submerged Resources Center, NPS

When veterans retire from the military—whether voluntarily or from injury—it can be a difficult transition. Gone is the camaraderie that gave their lives structure and often lost is a sense of purpose. A partnership with the National Park Service is helping wounded warriors to heal and restore connections by giving them a mission underwater.

For Jeff Pickard, the ringing in his ears never stops. It’s constant and sometimes will become a piercing squeal. “You know that noise that they put in the movies when an explosion goes off and it's that eerie, high-pitched noise? That's what I have,” Pickard says, "all the time."

Except...when he’s underwater.

When Pickard goes scuba diving, the ringing goes away, as does the pain in his arm. Pickard, a sergeant in the Army, was serving in Iraq when he was shot by a sniper in Kirkuk. It blew through his left shoulder in a part called the brachial plexus bundle and he lost full use of that arm for three years. And because the bullet hit his rifle, it detonated in his face, leading to his tinnitus. After several years of physical therapy, he’s regained some use of his arm.

But after scuba diving, Pickard says he can do more with his arm and it just feels better. For a long time, the military had him on high doses of pain medication, but that only eased the pain somewhat. Now, Pickard no longer takes meds for pain. “I’m completely off of it," he says, and after a recent dive trip his arm "stopped hurting for about a week and a half."

Same goes for the ringing, he says, “I don't know if it's the water and the pressure combined or just all of the water that's constantly in there," and he gets relief "no matter if it's saltwater or freshwater."

Pickard doesn’t scuba dive only to swim around and look at pretty fish, although he’s fine with that. On this morning in early March, he and five other veterans are at Lake Mead, the reservoir that was formed when Hoover Dam was built on the Colorado River in the 1930s.

Brian Moeberg, a veteran who dives with the Waves Project, takes measurements of a sand storage bin at the submerged Boulder Basin Aggregate Classifications Plant, where gravel, cobble, and sand were sorted to mix the concrete used to build Hoover Dam in the 1930s./Susanna Pershern, Submerged Resources Center, NPS

After loading their tanks, fins, and masks onto a flat-bottomed boat, the veterans, along with four employees from the National Park Service, motored a short distance from the marina near Boulder City, Nevada, to a buoy marking their dive site.

Pickard and the other divers are with the WAVES Project, which stands for Wounded American Veterans Experience Scuba. The Southern California-based nonprofit helps former military members recover from service-connected injuries both visible—and invisible. WAVES approached the National Park Service because for those who served in the military, having a mission is at their core.Switch Engine Locomotive

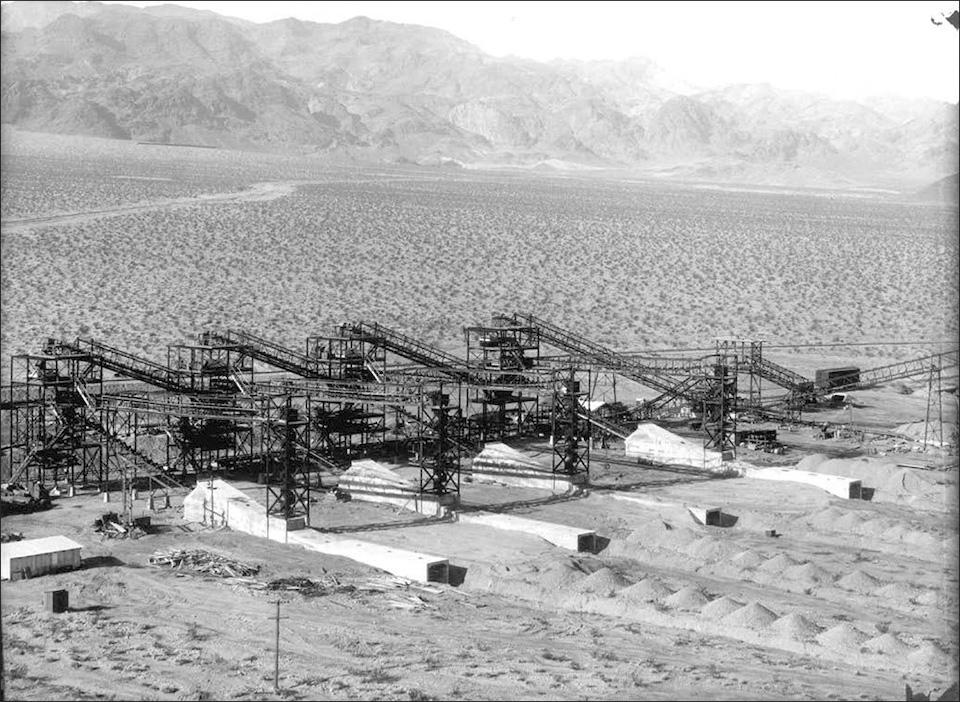

Today’s mission is to help the Park Service map a now submerged aggregate plant that was instrumental in building Hoover Dam. The Boulder Basin Aggregate Classifications Plant—a mouthful that everyone on board has lovingly shorthanded to the “Agg Plant”—started construction in October 1931 and began operations a few months later to prepare the sand, cobble, and gravel that went into making the massive amount of concrete it took to build the dam.

The six-acre site had a complex network of towers, hoppers, sieves, conveyer belts, tunnels, and rail lines that ran 24 hours a day, seven days a week, until the dam was complete. In 1935, when Hoover Dam closed and Lake Mead began to form, it was the era of big dams in the U.S. and most of the Agg Plant’s working parts were dismantled and taken to other construction sites, such as Parker Dam farther down the Colorado River. Left behind were the concrete footers, I-beams, tunnels, wooden railroad ties, and piles of sorted aggregate not worth moving. By the summer of 1936, remnants of the most advanced aggregate plant in the world at the time were submerged more than 200 feet.

Overview of Aggregate Classification Plant under construction, 11/01/1931. Main railroad line from vicinity of present marina area is visible in background. Concrete structures will provide access to conveyors after gravel piles form. Tower 4 is at left and scalping tower at right side of photo/U.S. Bureau of Reclamation

But water levels have dropped over recent decades due to aridification in the West and over-allocation of the Colorado River, to form the infamous bathtub ring on the lake’s desert edge, and now the plant is roughly 80-100 feet below the surface—well within the 130-foot limit of recreational diving.

Because Lake Mead won’t likely reach its original storage capacity anytime soon—if ever—Matt Hanks, an archaeologist with the National Park Service Submerged Resources Center explains that the goal is to provide information to both park visitors and the diving public about the site and its historical importance.

The national parks have vast cultural resources underwater, from shipwrecks to archeological sites, and divers with the Submerged Resources Center are tasked with surveying, maintaining, and protecting them. In terms of the Agg Plant, the objective is to provide a dive chart that will allow recreational divers to explore it safely. Because the tunnels in particular are likely a big draw, Hanks says the National Park Service wants divers to be aware of their inherent danger. The tunnels are likely unstable, given the weight of the water pressing on them for over 90 years. To discourage anyone from attempting to go inside, someone (not with the Park Service) placed a plastic Halloween skeleton with a hard hat at a tunnel entrance with a sign warning not to enter.

At the Lake Mead site, veterans—and Submerged Resources Center divers—work in pairs and stagger their time underwater. Each team steps off the boat's open bow clutching a measuring tape, pen, and clipboard in order to sketch the feature they’re mapping. Given the depth, they can only stay down for about 20-25 minutes at a time, and when they surface, someone on board announces, “Divers up!” Bubbles on the water give way to a pair emerging, who then tap their heads with a closed fist—the convention to signal that all is well.

One team is comprised of Richard (Rick) Bacon and Kristopher (Kris) Moorehead, both of whom dove the Agg Plant site last fall and remarked about the clear conditions this spring, where visibility is over 40 feet. In the fall, high levels of algae in the lake meant that often you couldn’t see your dive buddy and only knew they were there by tugs on the tape measure.

Both men say their wives found the WAVES program for them and that it’s not exaggeration to say it’s been life changing. Moorehead, who served in the U.S. Coast Guard, says his wife saw diving as a way “to try to get me out of the house and not be cooped up and depressed.”

Moorehead had never dived before signing up for WAVES. The program takes anyone with a VA rating, and the injury doesn't have to be combat-related. People who were injured in training are also welcome to apply.

Moorehead comes on board after his dive with a smile so big it could light up the sky. “I feel just so calm right now. It's awesome.” He says that feeling will last a good week or two, and after a whole week of diving, “I go back home and I'm definitely a better husband, a better father, and just have a better outlook on life and everything.”

His dive partner, Rick Bacon, represents the Task Force Dagger Foundation, which provides assistance to wounded, ill, or injured U.S. Special Operations Command members and their families.

Bacon was in the Army—spent six years in the infantry and 20 years in special forces until he was medically discharged in 2013. He says that when your career comes to an end in the military it can be a difficult time—even more so when it involves an injury or disability. The transition to civilian life was challenging for him—going from a mindset where “you're constantly processing your environment to see what could possibly harm you”—to being home, where you might “over-process” outside stimuli and find it hard to react appropriately.

Diving has provided serenity that calms Bacon’s mind and has helped his transition back to family life. Like Pickard, Bacon has tinnitus and it stops the minute he’s underwater—something the two marveled at and bonded over—when they met though WAVES.

(Front row) Susanna Pershern, Todd Thompson, Matt Hanks, J.R. Ryan, Dave Conlin, Kris Moorehead (Back row) Jeff Carlon, Brian Moeberg, Jeff Pickard, Jim Nimz, Rick Bacon/Submerged Resources Center, NPS

Todd Thompson will tell you that bonding among veteran divers is common and participants have come to consider WAVES their family. Thompson helps run the WAVES Project and says that even veterans who have moved on and no longer dive still keep in touch. Camaraderie is one of the four main pillars of the program, along with training, equipment, and service. The service pillar—having a reason to go dive—is where the healing happens, according to Thompson. Being able to help the National Park Service with what he calls “mission-oriented diving” gives divers the sense of purpose they might have lost after leaving the military.

Not only are the veterans helping at Lake Mead but also at other sites, such as Pearl Harbor, where they’re doing scientific research by measuring the rate of oil leaking from the wreckage of the USS Arizona as well as documenting the current condition of the ship. Three female veterans surveyed shipwrecks at Channel Islands NP off California, and veterans serviced more than a dozen marine buoy systems, assisted with coral nursery maintenance, and conducted lionfish removals at Dry Tortugas NP near Key West, Florida.

According to the 2019 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, in 2017, an average of 16.8 veterans died by suicide each day. “Diving is great,” Thompson says. “It's very therapeutic, but we want to see that one year, two years, three years, five years down the road that they're still doing something. If it's not diving maybe they got a job. If it's not diving...we just want to find what's right for them to help them heal.”

WAVES has done some research to try to understand why diving has such a healing effect. They’ve seen that after a single day of scuba diving there’s an up to 80 percent reduction in symptoms of PTSD for up to six weeks. There’s no clear explanation whether it’s from the pressure or the weightlessness, or because of breathing oxygen and nitrogen gas under pressure, or a combination of all of those things. Findings in a study by Loma Linda University suggest that "SUCBA diving provides a range of therapeutic benefits for veterans including improved occupational performance, and reduced symptoms of PTSD, depression, and stress. Key therapeutic features of scuba diving include the use of deep breathing techniques, experiencing comradery, and immersion underwater, which evokes a state of relaxation to help manage daily stressors."

The bottom line is that diving provides tangible relief. Relief so effective that maybe one day doctors might write a prescription?

Jeff Pickard would love that. He says he needs to go scuba diving multiple days, if he’s going down less than 50 feet. If he goes deeper, like 90 feet, he can dive two or three days and his arm will stop hurting for about a week. So, if a doctor would order him to dive 90 feet for 15 minutes, two times a week, he says, “Yeah. I'd be great with that.”

This story is underwritten by GC Green, Inc., a “Veteran-Powered” certified Woman, Native American, and Service-Disabled Veteran Owned Company. Mission and purpose are the core aspects of the DNA we carried from military service to our service beyond the uniform as a veteran owned business. From our inception we have been proud to adopt sustainability as that new mission and follow a business purpose of pursuing projects that promote a more resilient secure future and displays our commitment to diversity and inclusion.

Comments

Love this! Thank you.

I would like to spoeak to someone about this project for an article I am writing for a military magazine. Glenda Booth, [email protected]; 703 765 5233