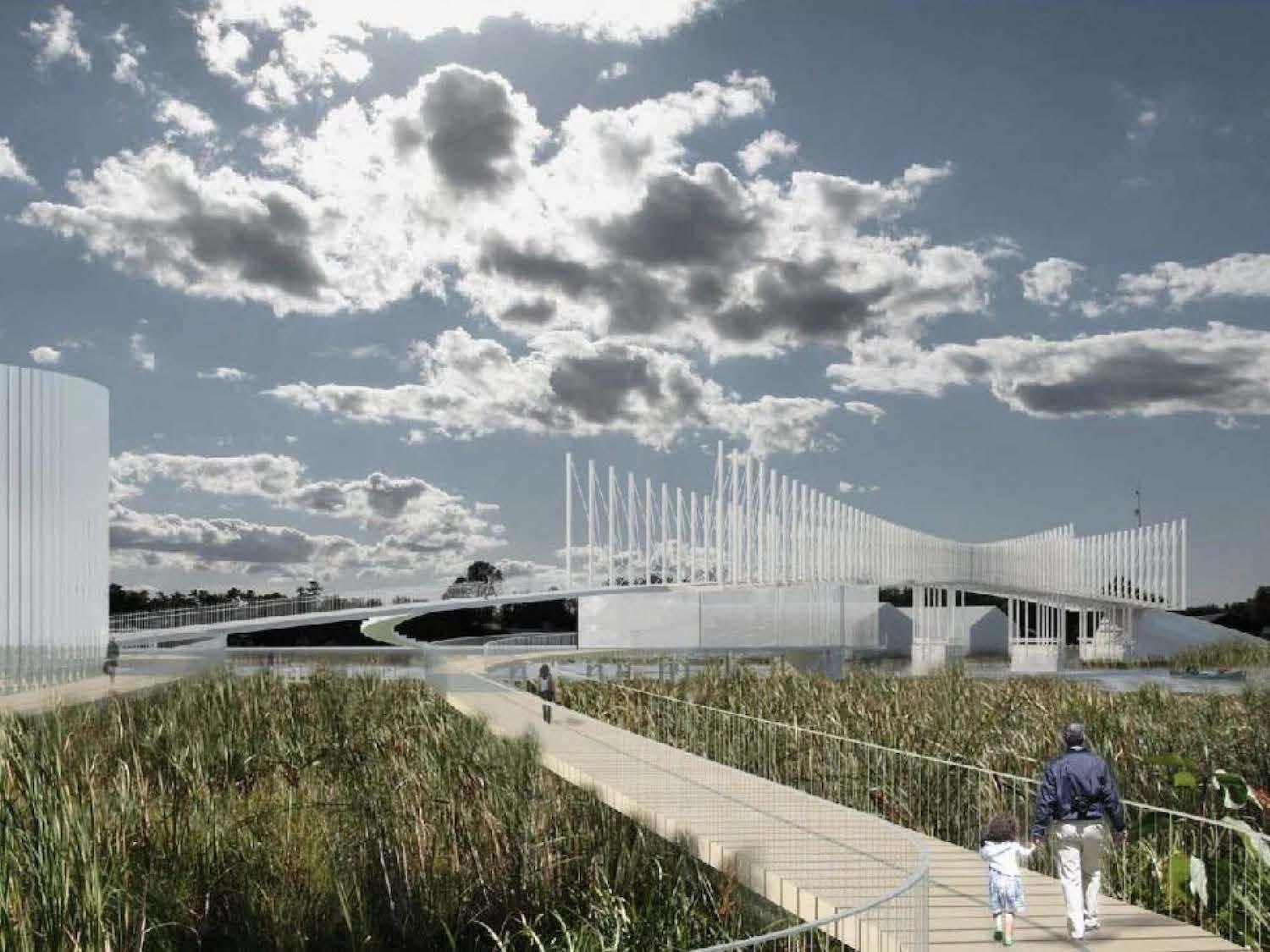

The concept drawings for the proposed Atherley Narrows pedestrian bridge, boardwalk and interpretive centre/Shim-Sutcliffe Architects, AECOM

Dozens of intriguing wooden posts jut out of the aquamarine water by the historic CN Rail swing bridge in Atherley Narrows and in the distance alongside Shotgun Island. But they’re actually bridge footings and not the ancient Indigenous fish weirs that make this Ontario spot a national historic site. Those are buried in protective layers of silt here in the shallow waters where Lake Couchiching and Lake Simcoe meet. Standing on an old steel trestle structure from the railway era that overlooks the channel, I wish I could have visited either 5,000 years ago or a few years from now if an ambitious rethink of the area succeeds.

Before the Great Pyramid of Giza was built in Egypt, this was a seasonal fishing spot for the Huron-Wendat people. Hundreds of families gathered every spring, carved stakes from saplings, and drove them into the lake bottom. They wove brush and vegetation through the underwater fence, waited for fish to find small gaps they could swim through and then waited in canoes with spears and nets. While preserving the harvest each spring and fall, everyone would socialize, trade, tell stories, hold ceremonies and make treaties and agreements.

Now this is Mnjikaning Fish Weirs National Historic Site, which is not far from Toronto and is one of the attractions along the Trent-Severn Waterway National Historic Site. But there’s almost nothing to see, unless you cross the highway to a forlorn area with a Parks Canada sign, an old provincial plaque and a dated interpretive panel with six paragraphs of trilingual (Ojibway, English and French) information along a paved path to the lake where something called “Grandfather Rock” stands in the middle of a concrete ceremonial area under the busy Highway 12 bridge.

The concrete ceremonial space, with Grandfather Rock, under the Highway 12 bridge/Jennifer Bain

“Nobody knows where to go, and as far as historic sites go, it’s probably the most underwhelming one in Canada,” admits Ben Cousineau, community researcher and archivist in the culture and heritage department for the Chippewas of Rama First Nation. “But it’s a fascinating story once you know all of it. This happened right here.”

It’s a story that’s still unfolding about one of the oldest human developments in Canada, and one of the largest and best-preserved wooden fish weirs in eastern North America.

The government is considering a $15-million (about $12 million USD) grant application from the Chippewas of Rama with the City of Orillia and Township of Ramara to replace the swing bridge that hasn’t been used for decades and is welded open so boats can pass. It hopes to replace it with a dazzling white pedestrian/snowmobile bridge, boardwalk, interpretive centre and First Nations ceremonial area that connects trails on either side of the narrows and tells the fish weir story.

Toronto architect Brigitte Shim, and some of the university students that she once taught, came up with a conceptual design for the bridge that pays homage to the shape of the fish weirs and mimics the way fish moved from open water, to the narrow channel and into the weirs.

A Parks Canada underwater archaelogist examines ancient fish weirs/Parks Canada

Mnjikaning means “the place of the fish fence” in the Ojibway language.

“We know it’s an old and ancient place, and it’s easy to think it’s just a way to catch fish, it’s just a way to eat. But the more you think about it, and the more you learn about Mnjikaning, you realize it was not just a restaurant, it was a rendezvous point, it was a first council hall, it was a place where trade happened, where families were made — literally. It was a social place,” Cousineau tells a recent virtual gathering of the Orillia Museum of Art & History. “It has been so much to so many people throughout history and we only know a little bit about its history.”

Mark Douglas, a Rama Elder, storyteller, knowledge keeper and Mnjikaning Fish Fence Circle co-founder, joins the Zoom gathering. He offers an appreviated version of centuries of fish harvesting at the narrows and what has happened since, a story that sometimes takes four hours to tell properly.

“A humungous number of our fish are called together there, various species going through at different times,” he recounts. “The perch come through. The suckers come through. The pickerel come through. The pike come through. The bass come through. It’s like they each have their own little window of opportunity and they scoot through the narrows going from the deep water of Simcoe and such, and the rest of the Trent, up into the shallower lake area of Couchiching — or Gojijiing, there’s lots of different names for this lake, Lake of the Many Winds.”

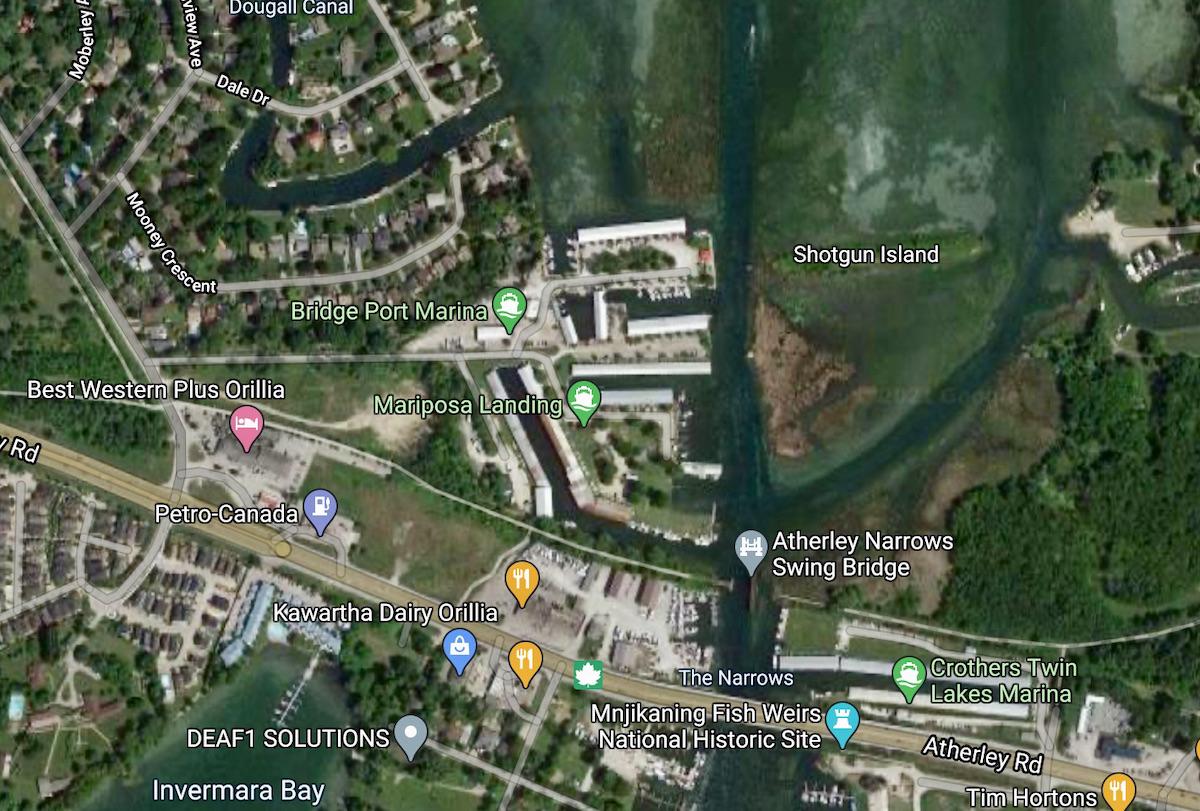

A satellite view of Atherley Narrows shows the swing bridge and the national historic sites on opposite sides of Highway 12/Google Maps

Douglas still marvels at a site that provided sustenance for 400 families for thousands of years, saying “that amount of food in one place begins to talk about the magic of the place.” When he has visited the narrows with Elders from his and other First Nations, they always feel something intensely spiritual. “They say it’s like somebody putting a warm blanket over your shoulders and getting a warm hug, and they talk about this energy that they sense and feel, and the kindness that evolves, or just oozes out of the water, up and just gathers people.”

According to Parks Canada's microcarbon dating, the fish weirs were built around 3300 B.C. during the Late Archaic period. The first time they were written about was September 1, 1615 when French explorer Samuel de Champlain travelled with the Huron-Wendat to attack the Iroquois and noted in his journal that he had seen numerous fishing weirs that almost closed the strait.

After that, the Huron were forced to leave the site, the Ojibway moved in but didn’t use the ingenious fishing technology and the weirs faded into “relative obscurity,” according a report by R. James Ringer when he was an underwater archaeologist with Parks Canada. Even so, the Chippewas of Rama promised to remain stewards of the fish fence.

A view from the trestle of wetlands and more old bridge footings by Shotgun Island/Jennifer Bain

Eventually, rounds of underwater archaeological explorations began, first by Royal Ontario Museum’s Walter Kenyon in 1966, and then by Trent University’s Richard Johnston and Kenneth Cassavoy in 1973 that included radiocarbon dating and helped pave the way for Parks Canada declaring the weirs a national historic site in 1982, even though it doesn't own any land at the narrows. "It is a sacred place representing an ancient and ongoing spritual bond between the Creator and all living things," Karen Feeley, public relations and communications officer for the Trent-Severn Waterway, says in a written statement. "The spirits of people, water, animals, birds and fish all come together in respect and gratitude at MnJikaning."

Faced with threats to the weirs from deterioration, recreational boaters, sport fishing, condos, marinas and other development, Parks Canada has over the years created speeds limits and no-wake zones in the narrows, brought in an underwater team and even excavated about 130 cedar, maple and birch stakes (with the blessing of the Chippewas of Rama) in 1993 for safekeeping. They'll be returned once there's a place to showcase them and in the meantime, three small travelling exhibits of conserved stakes can be loaned to three key local groups.

Hundreds of stakes remain, according to the Mnjikaning Fish Fence Circle, which was created in 1993. It commissioned a half-hour documentary called Journey to the Fish Weirs in 2002 and continues the fight to keep the area safe and cherished.

The Circle explains how the Creator gave each species of living things a different purpose. “The fish were told to come together at certain times of the year and to hold council. At these times, the people could more readily access them for food. Remarkably, in spite of all the changes the Atherley Narrows has undergone over the centuries, the fish still hold to their role in creation and come together at Mnjikaning every spring and fall.”

Ramara Trail ends at this old steel trestle with views of the swing bridge and wetlands/Jennifer Bain

I stumbled upon the fish weir story when it was part of Digital Doors Open Simcoe County in March. After watching the short video it posted — The Mnjikaning Fishing Weirs — Wendy’s Story — I learned about the connection to my hometown Toronto.

The fish weirs were once called ouentaronk by the Huron and tkaronto (“where there are trees standing in the water”) by the Mohawk. The spelling evolved to Taronto as the name slowly made its way 150 kilometres (93 miles) south where it was used for a fort at the mouth of the Humber River and eventually inspired the city of Toronto’s name, according to the Rama Historical Society.

Parks Canada doesn't have a management plan for Mnjikaning, but includes it with the one for the Trent-Severn Waterway, which will be updated this year. Everything is complicated by the fact it’s in the water where two lakes, a city and a township meet, involves old railway infrastructure and an area under a provincial highway and bridge, and is under the care of both a First Nation and a federal agency. Feeley explained that the unstaffed site is "managed through an informal collaborative agreement" negotiated during Highway 12 bridge improvements by Ontario's Ministry of Transportation in the 1990s.

There is one national historic site sign near the water/Parks Canada

The historic site designation is mostly for the underwater area and includes the original channel that runs to the northeast of the marshland surrounding the channels and the navigation channel that runs straight north and was first dredged in 1856 and 1857. Since the original channel has also been dredged, a linear island has been created between the two channels.

The oldest wooden stakes are clustered in the east channel, it says, and samples have provided carbon dates in excess of 5,000 years old to a time known by archaeologists as the Late Archaic. Another cluster of 12 radiocarbon dates falls within the time that the Huron-Wendat and their immediate ancestors lived around the narrows. Those are 75 to 350 years old.

Text for a new historical plaque and display panel is currently being vetted by Parks Canada and the Historic Sites and Monument Board of Canada.

The old Parks Canada trilingual sign and an Ontario plaque/Jennifer Bain

Cousineau says there are fears the controversial Rama Road Corridor project — which includes proposals for a waterpark resort, hotel and residential development nearby — could increase boat traffic, harm a provincially significant wetland and impact the remaining weirs.

But most people seem eager to see the new bridge plan succeed, linking the Millennium Trail in Orillia with the Ramara Trail in the Township of Ramara, and allowing pedestrians and snowmobilers to safely cross the narrows. The federal/provincial funding requested was submitted in 2019 and everything has been a waiting game since then.

“Right now we’re just completely on hold waiting for the word,” says Tim Lauer, an Orillia councillor and chair of the Atherley Narrows Bridge Project committee. He says the “wonderful story” behind the fish weirs is paramount, as is the physical connection of two trails. There's also an economic development incentive since this would surely be a big tourism draw, complete with the possibility of guided tours on land and water.

Parks Canada wrote to the federal government in support of the bridge project, saying the weirs "have a profound cultural and spiritual meaning for First Nations peoples and are a critical component of their cultural heritage" and the proposed pedestrian bridge, ceremonial First Nations sacred space and trail connection fits well with its "efforts to further enhance this national treasure." If the funding is approved, Parks Canada will consider relocating its signage to the bridge area.

A view from the trestle of the swing bridge and the old bridge footings (not fish weirs) in the narrows/Jennifer Bain

If approved, it could potentially be built in under two years. To be cost-effective, the swing span of the historic bridge — which dates to 1872 and was last expanded in 1920 — must be carefully removed so the new pedestrian bridge can sit on its pivoting pier. The proposal is designed to become a landmark that allows people to appreciate the area’s First Nations cultural heritage.

“The widening and narrowing of the bridge abstractly represents the fish weirs and the design of the structures simulates the vertical repetition of the elements,” according to the 2015 Municipal Class Environmental Assessment Environmental Study Report that Orillia commissioned for the project. “At present, there is very little understanding of the significance of the Mnjikaning Fish Weirs National Historic Site because one is unable to see the underwater weirs. Creating a vantage point to better understand the Narrows is essential to providing visitors with a deep understanding of the significance and sacredness of the Mnjikaning Fish Weirs.”

The interpretive centre would be tucked between the underside of the new bridge and the existing structural support for the former bridge. A wooden boardwalk would lead to the water. A circular walled enclosure without a roof would be placed at the water’s edge next to the wetlands for Indigenous ceremonies. There's no word yet on whether Parks Canada might reolocate its signs from the other side of the highway or what its future role might be, but this proposal seems like the best way to do justice to both this riveting story and this neglected national historic site.

“The bridge project is complicated, messy and expensive,” acknowledges Cousineau, “but it has been a dream of many people for a long time.” As Douglas puts it, "this was a special place, this is a special place, and not everybody senses this but there are people that do."

A bench near the trestle, wetlands and swing bridge has a message from the Mnjikaning Fish Fence Circle/Jennifer Bain

As I stand on that railway trestle admiring a gloriously rusty swing bridge in an empty channel while looking in vain for wooden stakes that are thousands of years old and submerged, I know this is a place that has long drawn people together, originally to fish and now to boat, hike, bike and snowmobile. On the drizzly spring day that I visit, it's a little lonely with just me, a smattering of boisterous Canada geese and mallards and a community's dreams for a recreational bridge that will help the Mnjikaning fish weirs story be widely told.

There's a bench just steps from the trestle with views of the undisturbed marsh and old channel. It's sponsored by the Mnjikaning Fish Fence Circle and a small plaque says it's to "honour the original peoples who four thousands of years gatherered here at the Fish Weirs, now a National Historic Site," and to acknolwedge the Chippewas of Rama who reconfirmed in 1836 that they would be caretakers of this special place.

"Maawndaa saa naa," the plaque reads. "The wonder of it all."

Comments

An important rich history that should be shared with everyone. Hopefully more people will read this and realize what we have in our own area.