Businessman, entrepreneur, rock climber, kayaker, pilot, conservationist, exceptionally accomplished and successful in all these endeavors, Doug Tompkins lived several lives in his 72 years, most notably one in the business world, the other in the realm of conservation. And despite the title, he had more than one wild idea – his is a story of one wild idea after another.

Businessman was first – well, not exactly – the climbing and outdoor part set him on a unique life path that preceded his first business venture. A gifted and energetic athlete as a young man, he took up rock climbing and met Yvon Chouinard when they were high school, establishing a lifelong friendship.

He managed to be expelled from high school, rejected going to college, developed his athletic skills in skiing and climbing, and then started his business career, founding the California Mountain Guide Service. Instructors in his school were Chuck Pratt, Tom Frost, Royal Robbins, and Yvon Chouinard, a Who’s Who of pioneering rock climbers of the Yosemite scene at the time.

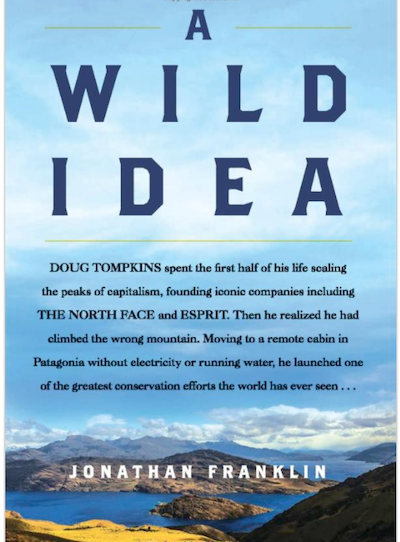

Next, he decided to go into business in San Francisco selling ski gear and climbing supplies, calling his infant enterprise The North Face. Chouinard was manufacturing and selling climbing hardware, mostly through mail order, and with Chouinard’s business counsel and his own savvy and bottomless energy, The North Face grew. He published a catalogue and, according to Jonathan Franklin, who chronicles Tompkins' life in A Wild Idea, “it garnered rave reviews, and The North Face Store became a cultural attraction – like an art gallery stuffed with crowds of beatniks, dirtbag climbers, and Doug and Susie’s circle of friends.”

The North Face expanded to three stores, but Tompkins found it too confining, and in 1967 he sold the company for $50,000.

Tompkins' wife, Susie, equally ambitious and entrepreneurial, co-founded her own business at this time, a clothing company. She was was just getting started and was nine months pregnant when Tompkins, Chouinard, Lito Tejada-Flores, and Dick Dorworth, later to be joined by Chris Jones, set off to drive from Southern California to Patagonia to climb Fitzroy, a granite fang that offered intriguing challenges to these elite climbers who called themselves on this trip the “Fun Hogs.”

Franklin’s account of this ultimately successful and famous climbing adventure is entertaining. Waiting out Patagonia’s notoriously bad weather in a snow cave, Tompkins and Chouinard had lots of time to kick around ideas about business back in the real world and by this time, with lots of time to talk, Tompkins could offer Chouinard some business counsel.

The biggest challenge was to wait. To kill time they told stories. Conversations were long, and rambling, and covered everything the Fun Hogs could think of, but often returned to life post-trip. What lay next? “One of Chouinard’s drives was, ‘I got to make some money. Must make some bread. I’m just spinning my wheels,’” remembered Jones. “And Doug was giving him advice. Doug was pushing him.”

Tompkins convinced Chouinard that hard goods (like ice hammers and pitons) were such great products that a single item might last ten years. Doug explained that selling shirts and pants was a repeat business, “That’s why Yvon got into the ‘soft goods’ business, because Doug convinced him,” said Jones.

Chouinard took his advice, and the result was Chouinard’s company, Patagonia. When he got home from this adventure, Tompkins cast about for his own next business venture and decided to join Susie and her partner in building their clothing company. This arrangement would allow him to get away on outdoor adventures for weeks or months at a time with Susie minding their interest in the business.

Franklin devotes several chapters to the story of how this clothing company came to be Esprit and Tompkins' role in its rise. He “broke many rules and challenged truisms.” He was not the company’s CEO but dubbed himself the “Image Director,” obsessing over aesthetic details and marketing. As Franklin tells it, drawing liberally from interviews of players in the story of Esprit, Doug and Susie complemented each other in their roles at the company.

Back in the days of The North Face, Doug had “capitalized on a deep cultural shift,” the rise in American culture of outdoor recreation. He did it again, according to Franklin, with Esprit, diagnosing the 1980s “as an age of narcissism and pursuit of the good life.” The Esprit clothing line played to this, and was immensely successful, becoming “famous as a maverick company, as the cutting edge of teen fashion.”

Doug and Susie were business celebrities, living the high life and traveling the world, but he was dissatisfied. By the mid-1980s he began to think he “was doing the wrong thing . . . making a lot of stuff nobody needed.” He had to do something else, and a growing environmental awareness suggested what that might be.

Tompkins had fallen in love with Chile as a young man, training there for ski racing, returning with the Fun Hogs to climb Fitzroy. Influenced by eminent conservationist David Brower, activists like Dave Foreman of Earth First!, and others, he embraced conservation and decided philanthropy would be the best way he could contribute. In 1991 he sold his shares in the Esprit Brand and its divisions and established the Foundation for Deep Ecology.

Franklin writes, “After twenty years building Esprit into a global brand, he switched sides. Could he now reverse all the environmental damage he caused while amassing this very fortune?” He began with grants to hundreds of direct-action conservation groups while engaging in a crash course on conservation and what should and could be done. “At his hilltop home in San Francisco, Tompkins gathered scientists, authors, young forestry activists, grizzled vets like Foreman, and top biologists, including Michael Soulé, the ‘intellectual grandfather’ of the scientific field of conservation biology.” Eventually he turned his attention to Chile where he bought a rundown farm, indulged his passions of climbing and kayaking, and pondered how he could best pursue his new passion.

By now a veteran and skilled pilot, Tompkins bought a high-horsepower, lightweight plane and began exploring his new neighborhood. He decided his strategy would be to buy land to save it, even traveling to Siberia with friends, including journalist Tom Brokaw, to see if he might invest in land there to protect habitat for bears and tigers, but decided against it. “The corrupt practices of post-Soviet capitalism involved too many bribes, too much mafia, and too many dubious characters. Tompkins knew that forest land in South America was just as cheap, and in Chile, he believed, the locals played by the rules. He would focus his attention there.”

Tompkins' first initiative in South America, he decided after surveying maps of southern Chile, would be in Patagonia. He envisioned a 500,000-acre private conservation initiative he would call Pumalin. Franklin describes in detail how Tompkins set about to pursue his vision, buying up land and assuring suspicious Chilean people and authorities that, with his pledges to donate Pumalin ultimately to the Chilean people, he was not just another scheming gringo bent on exploiting the land and its people.

And, of course, he was thwarting development, which made him many enemies.

Franklin writes, “Chile had been deprived of nearly every Earth Day celebration from 1973 to 1990 as military curfew and repression kept a lid on most forms of social organizing. Activists had been specifically targeted. By the early 1990s environmental awareness was just emerging and repeated promises by Tompkins to save the forests and protect the deer felt like a weak cover story for something far more nefarious.” Tompkins would not only have to fight entrenched interests both inside and outside of government bent on exploiting the areas he wished to save. He would have to win over suspicious villagers and potential allies. Franklin quotes Hector Munoz, a high-level official in the Chilean Ministry of Interior when Tompkins launched his initiative.

The problem was the magnitude of his philosophy. We found out he was a follower of Deep Ecology, a believer in biocentrism, which means that nature comes first, and that humans are just another element of nature and that all beings have the same rights. He even argued with me that rocks have the same rights as human beings! That’s when we began to understand his ideological character; this man was absolutely convinced of his beliefs. He had an incredible fanaticism, and deeply held convictions.

Chileans had not encountered anyone like this, and Munoz was right about Tompkins’ convictions. He would use all his business savvy and wile over the next few decades to realize his conservation dreams, struggling with many obstacles in Chile.

He could not, and did not, do this work alone. A key ally who came into his life as Tompkins was beginning was Kristine McDivitt, CEO of Patagonia, Yvonne Chouinard’s company. They married in 1994, and Franklin characterizes her as an “intense and brilliant partner” who complemented Doug in many ways and changed him. He quotes Chouinard: “He was more bombastic before. He was, It’s my way or no way. He would argue everything, didn’t see anyone else’s viewpoints. A lot of people did not get along with him because he was too self-centered and too sure his opinion was the only one. She was able to control him and really change him around.” They became full partners in the work, as Franklin’s account makes clear. Franklin quotes environmental historian Harold Glasser: “They were a team,” he said. “Doug was the sort of stalwart bulldog, but she was the one who know how people work and smoothed things over and knew how to bring out the best in people. Kris is the one who always seemed quite rational, really open-minded, and a very good critical thinker.”

Harassed and threatened by opponents in Chile, the Tompkins were surprised and pleased to be invited to consider work in neighboring Argentina. The Argentine national parks director issued an invitation and “A list of biodiversity hotspots was delivered in a tone of collaboration distinct from the confrontations in Chile.” Doug and Kris took him up on his invitation and after looking around they fixed their attention to an area known as Iberá.

This was a vast wetland, a lawless place and “not a place where an arrogant yanqui could invest without first understanding the local landscape.” Part of Tompkins’ problems in Chile stemmed from his unwillingness, as he began buying up land there, to understand the local landscape and its people. He eventually learned from this, and with diplomatic Kris’s help, he approached the work differently.

Ignacio Jimenez, a Spanish wildlife biologist who worked with the Tomkins for a decade in Argentina, commented on the new modus operandi the Tompkins team brought to their work there.

One of the keys to Doug and Kris’s success, and it’s imperative to stress it, is their commitment to live in the areas where they worked. That’s a huge difference from any other NGO. They decided they were going to make parks and that they were going to live there. That gave them a whole different level of control about what was going on. Doug was flying over these lands, so he could see everything from the air. He understood local politics, which was critical. With Kris, they hired local people. So, they combined their American business knowledge and values with knowledge from the locals.

As the Tompkins’ land acquisitions in Chile and Argentina grew, so did Kris’ role. According to Franklin, “Kris was far more than peacekeeper. She was the secret administrator of projects building bridges with wealthy donors, smoothing ruffled feathers and sorting through her husband’s wild ideas.”

The Tompkins' work in Argentina involved the same approach they were working on in Chile, buying land with potential for protecting and restoring biodiversity with the idea of protecting and even returning species to those lands. Argentina proved more amenable to their approach than Chile, and while they continued with their frustrating Chilean initiatives, they achieved considerable success in Argentina. They made possible the creation of Monte Leon and Iberá national parks, which encouraged their continued labors in Chile where, in 2005, Corcovado National Park was established. Conservation initiatives they launched in Argentina continue to this day, with Tompkins Conservation collaborating with their affiliate independent NGO Rewilding Argentina to create and expand protected areas, and restore missing species and processes to Argentine parklands.

Franklin recounts the role the Tompkins played in fighting a plan by a group of multinational corporations to build dams in Patagonia that was ultimately successful. He describes how Tompkins went to sea on a Sea Shepherd Conservation Society ship intent on thwarting a Japanese whaling operation; how he and Kris embraced rewilding, working to bring back jaguars, protect pumas, and reestablish the rich biodiversity of his and surrounding lands; and finally how Doug and Kris came up with a grand vision for conservation in Chile. Land and sea routes could connect a dozen national parks in southern Patagonia in an arc of over a thousand miles.

“Tompkins needed an image, a unified concept. Then it came to him: he would rebrand the disparate ecosystems as a single entity.” He would call it the Route of Parks and it would involve one grand mega-donation to establish a system of linked national parks in Patagonia. Franklin writes that approaching 70, Doug felt his time to realize his grand conservation ambitions might be nearly up. He, Kris, and their colleagues launched their campaign to make this mega-donation possible.

Sadly, Doug did not live to see this vision to fruition. He died, ironically given his great career and skill as an outdoor adventurer, in a kayaking accident on Patagonia’s Lake Carrera in 2015. Franklin writes of this tragedy in a riveting chapter titled “Ambushed in Patagonia.”

But the loss of Doug was not the end of the mega-donation story. Kris continued to work on the Route of Parks and made an offer to the Chilean president. Franklin writes, “The terms of the offer were complicated in the exacting details but simple in the overall scope. Tompkins Conservation would donate 1.2 million acres of land with a combined $90 million worth of infrastructure to CONAF – the Chilean National Park Administrators. In exchange the government would bundle together ten million acres of federal lands and promise to create five new national parks, expand three others, and launch a new era of economic development for Chilean Patagonia.”

In January 2018, agreement was reached between Tompkins Conservation and the Chilean government and one of Doug Tompkins' wildest ideas was realized.

Jonathan Franklin is a journalist and his major sources for this story are 165 interviews, which he quotes liberally throughout the book. He does not spare his subject, who was a complicated man. He sums up what he found in his research in an “Author’s Note.”

This book is my journey into one man’s love affair with the wild. The wild mountains, forests, and rivers. Doug Tompkins was also wild. Competitive, hyperactive, and as flawed as his friend and neighbor Steve Jobs, with whom he argued at parties. Tompkins was an environmentalist who drove a red Ferrari. A multimillionaire who preferred to sleep on a friend’s couch. He was a stickler for details, yet he hardly noticed his two daughters right before his eyes. Hard-nosed, arrogant, and argumentative, he despised compromise.

He adds:

Like the way he drove cars and paddled kayaks, Doug Tompkins never looked back. Yet, for all his faults, I found myself transfixed by this rock climber who at the age of forty-nine and atop the peak of capitalism took a deep look around and admitted to himself “I’ve climbed he wrong mountain.”

The story of Doug’s life, and of his remarkable collaboration with Kris, deserves to be widely known. It is remarkable in so many ways. There is nothing like it in the history of conservation. Philanthropists like the Rockefeller family have made national parks possible through donations, but no one I know of has experienced an epiphany and then dedicated life and fortune to conservation on the scale of Doug Tompkins. If only, in this age of billionaires, more would step up to address the challenges of biodiversity loss and rewilding.

In his closing paragraph, Franklin writes that, “Doug Tompkins never flinched from his conviction that, in the words of Ed Abbey, 'sentiment without action is the ruin of the soul.'”

To the young activists he met while battling to stop the Japanese whale hunt, Tompkins had posed a challenge: “Are you ready to do your part? Everyone is capable of taking up their position to use their energy, political influence financial or other resources and talents of all kinds to be part of a global movement for ecological and cultural health. All will be useful. There is important and meaningful work to be done. To change everything, everyone is needed. All are welcome."

The legacy of Doug Tompkins is huge, and the work continues today as Kris Tompkins leads Tompkins Conservation and the rewilding of lands in Chile, Argentina, and other parts of the world. They offer us a shining example of what can and must be done to protect wildness and the world on which all human society depends. The story of Doug Tompkins' wild ideas and how he and his allies brought them to fruition, in business and especially in conservation, makes for an engrossing and informative read.

Comments

In the past several years since I discovered National Parks Traveler i have been exposed to many interesting books. I have not been disappointed! I just ordered this one and am looking forward to reading it.