The charred aftermath of the Dixie Fire in Lassen Volcanic National Park. / NPS, Amanda Sweeney

On The Comeback Trail

Three national parks forge a way forward after devastating fires and highlight the important role of park friends groups.

By Kim O’Connell

Smoke still clouded the air, and blackened tree stumps were still burning, when staff at Lassen Volcanic National Park began the arduous process of inventorying the damage wrought by last year’s historic Dixie Fire. They could see with their own eyes that trail bridges, signs, and sections of forest were torched. Satellite imagery confirmed the rest: The flames had cut a large, black swath through the national park.

“We use the park highway as the primary fire line, and very successfully,” says Jim Richardson, park superintendent, meaning that the road serves as a built-in firebreak. “So by and large when people drive the park highway, they will see black on one side and green on the other side.”

By the time the Dixie Fire was fully contained on October 26, 2021, more than 100 days after the first embers ignited in a northern California canyon, it had burned nearly 1 million acres, an area larger than Rhode Island. It is one of several large wildfires that have torn through the West in recent years, many coming near and into national parks. At press time, the massive Cerro Pelado wildfire had reached the edges of Bandelier National Monument and Valles Caldera National Preserve in New Mexico, sending park staff and firefighters into overdrive to protect the parks’ facilities and natural and historic resources.

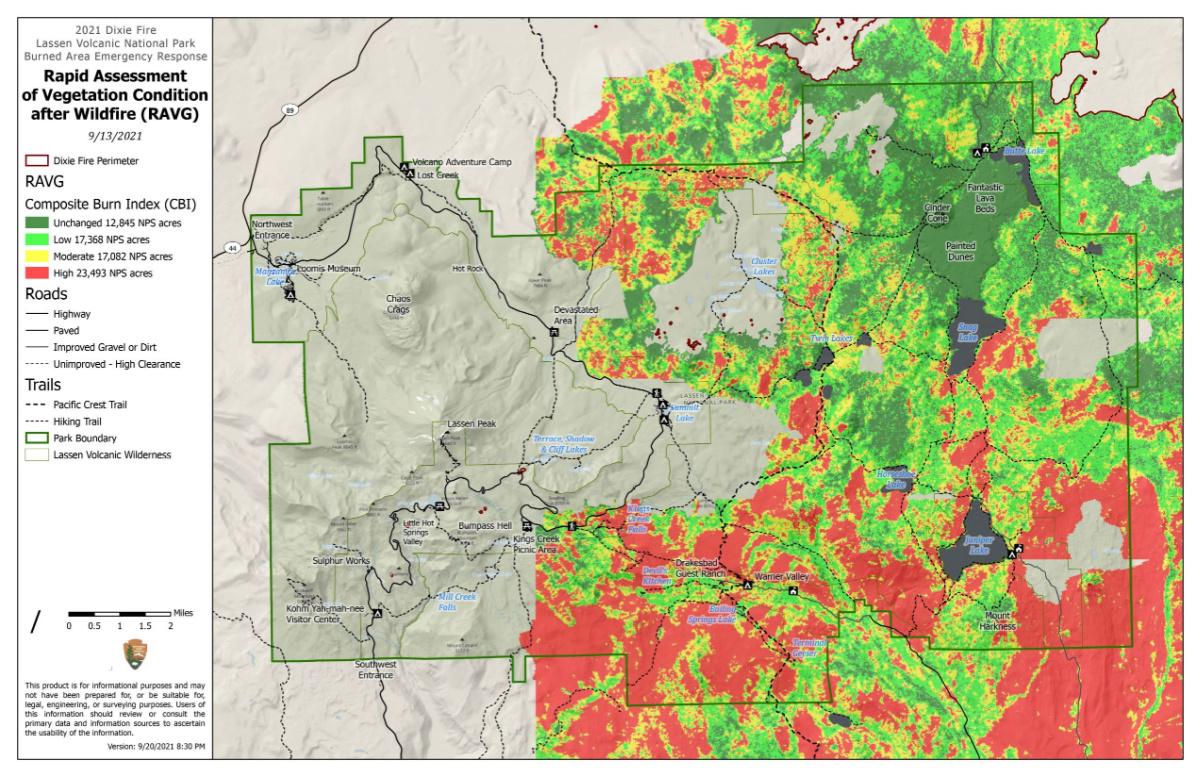

A map of burned vegetation at Lassen Volcanic shows that, while most of the park's vegetation burned at low to moderate intensity, a significant percentage of vegetation burned at high intensity, which is harder to recover from. / NPS

It’s an experience three national parks know all too well—Lassen Volcanic, Sequoia, and Rocky Mountain—which have all suffered from tremendously destructive wildfires in the last couple years. With assistance from park friends groups and other park constituents, these places are now forging significant paths towards recovery, while finding new opportunities for outreach and education. Where park friends groups used to focus on running gift shops or providing visitor information and activities, now they are increasingly called upon to be an essential source of park funding when federal disaster dollars just aren’t enough.

At Lassen, the scars of the Dixie Fire are still fresh. Dixie (named for a road near where it started) is now the largest single fire in California history, and it’s the largest fire in Lassen’s history as well. (California has had larger complex fires, meaning two or more fires burning in proximity to one another.) The Dixie Fire footprint includes 73,240 acres within the park, representing 69 percent of the park’s acreage, although park staff says that more than half the park, which showcases volcanic landscapes with sprawling cinder fields, was unaffected since vegetation on nearly 13,000 acres was essentially unchanged. The fire burned at various levels of severity and damaged or destroyed 12 park structures, including the historic Mount Harkness Lookout.

“We know that several of our wooden trail bridges burned during the fire,” Richardson says. “Since the trail system crosses some quite challenging creeks, that’s going to be difficult to access for this summer….We probably have three or four times as many trees down across the trails as normal, and many of those are burned trees.”

In areas where the fire was lower intensity, Richardson explains, park vegetation will bounce back the way it does after prescribed burns, a common management tool in the national parks. But in the high-intensity burn areas, where trees look like used matchsticks, it will take a long time and a lot of effort and money for the park to replant, rebuild, and do other restoration work to help the park rebound.

The fire was still going when the Lassen Association and Lassen Park Foundation, in partnership with the park, created the Lassen Resilience Campaign to raise money and aid in recovery efforts following the Dixie Fire. Superintendent Richardson called a meeting with the two groups as soon as he could.

“He knew there would be lots of federal funds that would flow to the park to mitigate a lot of the damage, but virtually all of the federal funds are earmarked for specific projects,” says Joe Kelly, treasurer for the Lassen Association. “We knew there would be a myriad of things that would fall between the cracks of those federal funds, and he was looking to us, primarily the Lassen Association, to do fundraising.”

Kelly immediately thought of Jake Early, an admired California artist and printmaker. They commissioned a limited-edition print from Early to sell as a fundraiser for the Lassen Resilience Campaign. The silkscreened print shows Lassen Peak against a bluebird sky, with green forests and the park’s famous hydrothermal areas in the middle ground. A couple charred trees in the left foreground acknowledge the fire, but it’s balanced out by a healthy pine tree on the right, and two pinecones on the blackened ground, a sign of the rebirth to come. The prints have been selling well, according to the association, and could bring in six figures for the park.

While Dixie was burning in northern California, Sequoia National Park was also in flames. Last September, two fires converged to become the KNP Complex Fire, which burned more than 88,300 acres before it was contained. This fire, coupled with the SQF Complex Fire of 2020, has resulted in the destruction of nearly 20 percent of the world’s sequoia trees. Sequoias are an endangered species, and the park contains some of the most important remaining sequoia groves on the planet as well as the General Sherman, the world’s largest tree with a 36-foot diameter at its base.

“The park is open, and you will see burned-up trees, not just sequoias,” says Tamara Marks, director of philanthropy for the Sequoia Parks Conservancy. “As you approach the Giant Forest, near Beetle Rock, you will see burned sequoias. You’ll see how close the fire got to trees like General Sherman, but you’ll also see the astounding work that the firefighters did to save trees like that.”

Even as the KNP fire raged on, the Conservancy embarked on a fundraising appeal that has already drawn more than $600,000 for park restoration work, which might include sequoia propagation and replanting, Marks says, as well as scientific research by academic partners. “It’s a drop in the bucket in terms of the work that needs to be done,” she says. “We’re about to launch the second part of that campaign, which is called the Big Give….We have incredible constituents, an incredible donor base, who are spiritually and emotionally connected to our parks. They continue to come through.”

Going forward, the park faces a triple threat, Marks says: “Drought, beetle kill, which was not expected and is taking park scientists a little by surprise, and wildfire.” Sequoias’ thick bark and tannin levels offer them natural protection against insects, but ongoing research by the NPS and the U.S. Geological Survey has found that sequoias are dying from bark beetle attacks that are taking advantage of drought-stressed trees. More severe and frequent droughts are an expected climate change impact, so these attacks are likely to worsen.

Sequoia cones and seeds after a wildfire. / NPS, Anthony Caprio

In Colorado, the Rocky Mountain Conservancy has been similarly fundraising to help Rocky Mountain National Park recover from the two largest wildfires in the state’s history, the Cameron Peak Fire and the East Troublesome Fire of 2020, which burned 30,000 acres inside the park’s boundary. “The 30,000 acres is 10 percent of the park and represents a lot of devastation,” says Mike Allen, the Conservancy’s philanthropy director. “To aid in the park’s recovery, the Conservancy stepped in, and we created a new fund—the Wildlife Restoration and Healthy Forests Fund—to seed the recovery of the park, to recover vital trail infrastructure, and begin to restore plants and wildlife.”

The approximately $400,000 raised to date has already been earmarked for wildfire recovery and prevention efforts, including the launch of Youth Fire Corps, which gives young people experience working alongside the park’s fire crews. Last year, the fire corps built slash piles, which are piles of cut logs to be burned in wintertime, to reduce forest density and limit future fire spread. Rocky Mountain’s new fund, like the efforts at Sequoia and Lassen, was also supported in part by donations from national park apparel company Wild Tribute, which gives 4 percent of its proceeds to natural and historic sites in need.

“For better or for worse, and this is true for many national park nonprofit partners, unfortunately when there are disasters it is a call to action for the park partner,” says Savannah Boiano, executive director of the Sequoia Parks Conservancy. “We’ve perked along on this old model of what a park partner is, but the future for national parks is beyond that model. [These wildfires have] put a fine point on what we are here for. We are here for something bigger.”

This article is made possible in part with support from Wild Tribute.

A blackened valley at Lassen Volcanic. / NPS, Amanda Sweeney

Comments

What is it with people using Rhode Island to compare the size of something? It's not like anyone has the size of Rhode Island memorized, it's not a useful comparison.

I always enjoy reading Kim O'Connell's contributions to the Traveler. They are well-written and understandable (at least, to me). As for using Rhode Island as a comparison, the size of the state (approx 776,900 acres) is much closer to the size of the Dixie Fire's area of destruction ("nearly one million acres") within Lassen Volcanic National Park than, say, using Texas or even Connecticut as a comparison. I suppose Ms. O'Connell could have written that the destruction was a little under the size of Delaware (approx 1.2 million acres). To me, Rhode Island is a useful comparison, because it's a comparison of the size of an entire state to the amount of destruction this single fire wreaked on this particular national park.

THank you for including Sequoia Parks Conservancy!

George, it may be something as simple as "RI is the smallest state", similar to a comment of "more land mass than Alaska". Kinda like putting a dime on a sand table for comparison to an artifact being photographed.