Parks Canada heritage interpreter Jacelyn Perret shows the many uses of the traditional Métis sash while on a tour of Batoche National Historic Site/Jennifer Bain

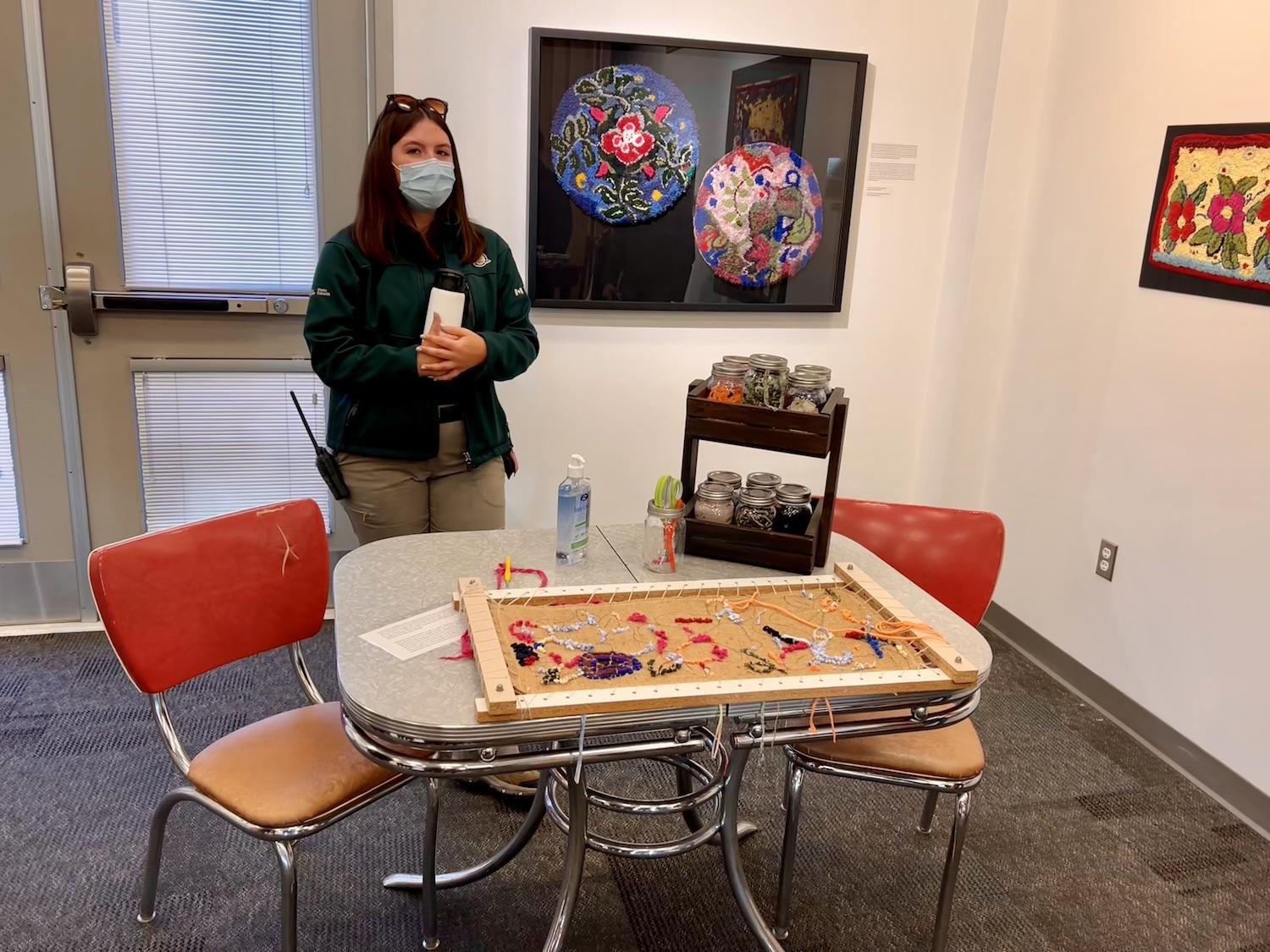

In the café at Batoche National Historic Site, cooks transform bison from Parks Canada’s herd into stew and burgers, and local Saskatoon berries into iced tea and tarts. In the exhibition room, I try rug hooking while surrounded by the colorful creations of traditional Métis rug makers like Margaret Harrison. In the gift shop run by the Friends of Batoche, I buy a book that shares Métis Elder stories about important river plants in the area like pasture sage, chokecherry and cattail, and notes their names in Michif.

There is much to learn here in Saskatchewan where the 1885 Battle of Batoche during the North-West Resistance (let’s stop calling it a rebellion) ended with the surrender of Métis leader Louis Riel. But the despair that came after that historic four-day battle over land titles — Riel was unjustly hung for treason and the village of Batoche was left in ruins — is offset by the joy of having tangible proof through art, food and community that Métis culture is thriving.

“I think sometimes when we think of historic sites, we think about a snapshot of the past,” says site manager Shirley Johnson. “But Batoche, because of our connections to the community and the profound meaning of what happened here, is a living site. And having current artists here is so important because it shows Métis culture continuing.”

Batoche site manager Shirley Johnson shows her favorite hooked rug by Elder Margaret Harrison/Jennifer Bain

Declared a national historic site in 1923, Batoche commemorates the 1885 armed conflict between the Métis Provisional Government and the Canadian government that was part of the foundation of the Canadian West. It also commemorates the Métis community at Batoche and the Métis river lot system.

About 14,000 visitors come to this stretch of farmland, prairie and Trembling Aspen forest along the South Saskatchewan River between May and October each year to celebrate Métis pride, language and cultural traditions. Earlier this year, Parks Canada announced that it will transfer 690 hectares (1,705 acres) of land on the west side of the river to the Métis Nation – Saskatchewan.

“The Batoche grounds have always been important to our Métis citizens, our history and the resistance,” Glen McCallum, president of Métis – Nation Saskatchewan, said at the time. “This was the defining moment for us as Métis in Saskatchewan. The repatriation of Batoche lands is tangible and starts the path to reconciliation. There is a deep connection for us at Batoche. We, as Métis people, will determine the best use of this land that will respect our ancestors’ ultimate sacrifice in how we will honour and uphold their vision.”

Thirty-two hectares (79 acres) to the northeast of Batoche were previously transferred to Métis ownership in 1996 and now serve as grounds for the annual “Back to Batoche” festival. That leaves Parks Canada with 310 hectares (766 acres) of land on the east side of the river to tell the story of Batoche. The site is co-managed by the Métis Nation.

At the rotating exhibit room in September, heritage interpreter Jacelyn Perret lets visitors try rug hooking/Jennifer Bain

To belatedly understand this pivotal Canadian battle that wasn't covered in school, I take a tour with Parks Canada heritage interpreter Jacelyn Perret, who shares that she is 22 and only discovered her Métis heritage five years ago. The Métis draw their lineage back to the fur trade when French, Scottish and English men married First Nations women.

“My family never really talked about our ancestry or heritage,” says Perret, remembering the shame that was one associated with being Métis. “I always say I grew up with the culture but not the title. I knew we were different in a sense. Until I was 12 years old, I thought everybody grew up eating stew and bannock.”

After she started working at Batoche, a text from her grandmother changed everything. “The moment the puzzle pieces clicked was in 2017, my first summer working in Batoche (I was 17). I got a text from my grandma that said something along the lines of `Jace forget to tell u Patrice Fleury is ur great great great great grandfather.’ And then with a little deeper dive together, the family tree and my love for history grew and grew and by the next summer I was incredibly proud of my ancestry and culture.”

Now Perret is a proud Métis actor, singer, dancer and playwright who has taken up beadwork. In 2019, she wrote her first one-act play and calls Invisible Minority “both a personal exploration of the importance of cultural identity in today’s generation, and a retelling of the North-West Resistance of 1885 through the eyes of the women that experienced it.”

At Batoche, the modern visitor reception center houses a self-guided museum.

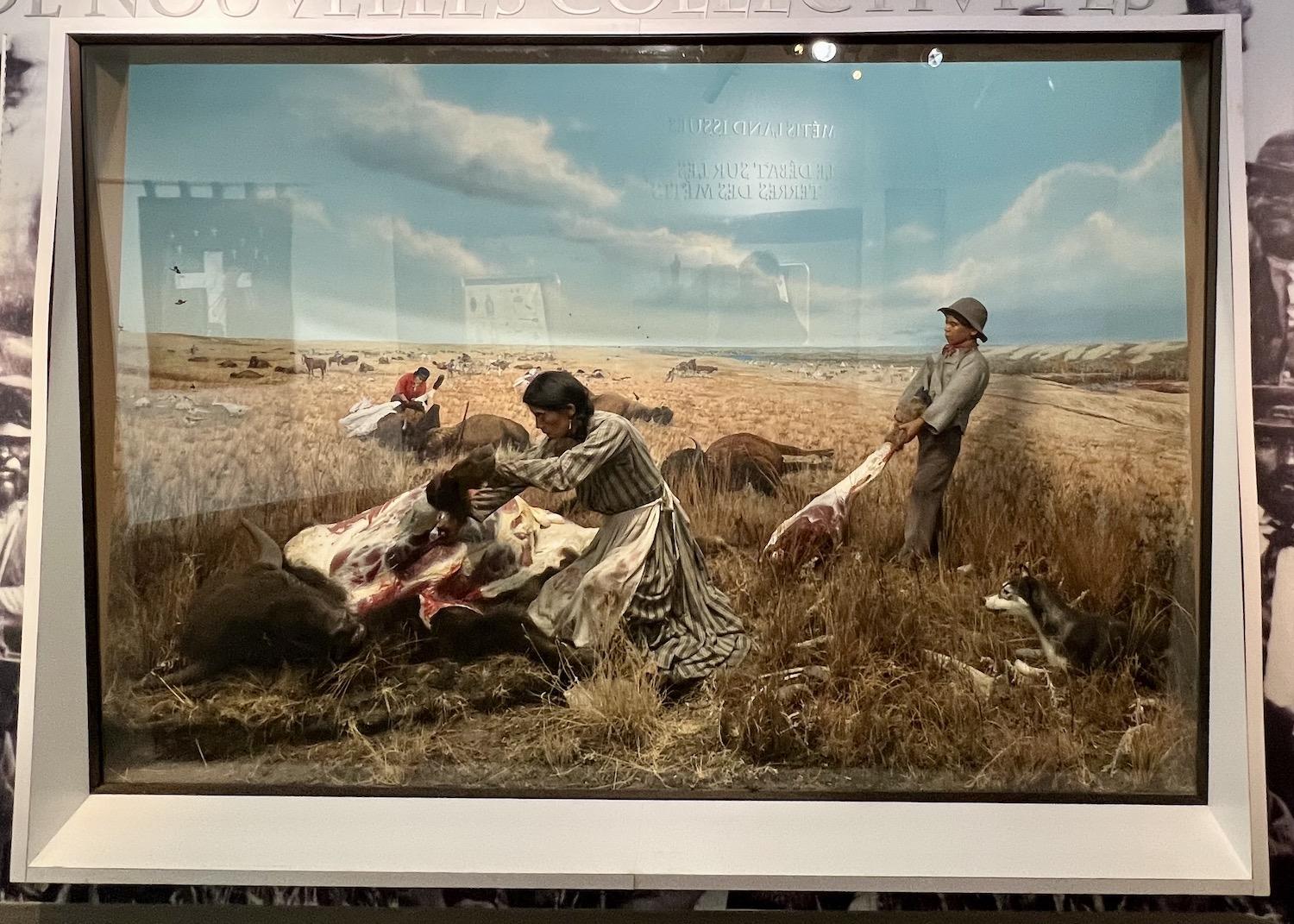

In the visitor center museum, a diorama shows Métis life during the buffalo hunt/Jennifer Bain

The story starts in the 1870s during a time of rapid change in the Canadian northwest. The Métis once dominated hunting and freighting during the fur trade. But when two powerful trading companies (Hudson’s Bay and North West) that they worked for merged, and then the bison economy collapsed, they turned to farming.

The Métis community in Manitoba, grappling with the arrival of settlers from eastern Canada, started to migrate west for what Parks Canada describes as “open country, political autonomy and new economic opportunities.”

The remains of a store owned by Xavier Letendre, whose nickname Batoche was given to the village that sprung up here/Jennifer Bain

In 1872, wealthy Métis merchant Xavier “Batoche” Letendre established a ferry service on the east bank of the river here at the site of the village that would soon bear his nickname. He built a store and warehouses on Lot 47 at this strategic point where the trail from Winnipeg, Manitoba to Fort Carlton (now a Saskatchewan provincial park) crossed the river.

As other Métis settled along the river, laying out farms in their traditional long river lot fashion, Batoche became the commercial hub. In 1882, a rectory with a chapel, school room and post office was built. A church followed in 1884. By 1885, about 500 people called Batoche home while 1,200 lived in the area.

Interpretive panels at the East Village viewing platform help you imagine the time when the village of Batoche was flourishing.

But problems arose getting legal title to their land in a system that now favored the Dominion Lands grid system over the Métis river lot system. At the same time, First Nations people struggled to get the food, equipment and farming assistance they had been promised in treaties with the government, and other European settlers were also unhappy with government policies.

Métis leaders let by Gabriel Dumont drafted petitions, but the government didn’t respond. In 1884, a delegation traveled to Montana to invite Riel, the Métis leader who negotiated Manitoba’s entry into Canada as a province in 1870, to join this new struggle.

In 1885, widespread opposition to the government’s land policies provoked an armed resistance against the dominion’s troops. Five battles broke out in Saskatchewan, starting at Duck Lake and ending at Batoche.

An image of Métis leader Louis Riel, emblazoned with one of his famous quotes, greets visitors to Batoche/Jennifer Bain

The Battle of Batoche lasted four days from May 9 to 12, 1885. Riel, Dumont and 300 supporters defended the village from rifle pits they dug themselves. The North-West Field Force, commanded by Major-General Frederick Middleton and numbering 800, attacked and won.

The village was left in ruins, homes burned, personal belongings and cattle looted by militia troops. Dumont fled to the U.S.. Riel escaped but soon surrendered and was hanged Nov. 16, 1885 for high treason. Considered a hero/martyr by some and traitor/madman to others, he has never officially been exonerated. Canada finally recognized Riel as a founder of Manitoba in 1992, and Manitoba named a February holiday for him in 2007.

“What makes Batoche relevant today?” asks a message on an oversized chalkboard outside the museum.

“Teach the history to the kids unedited,” reads one visitor's answer.

“Truth,” reads a second.

“Generations reconnecting,” reads a third.

A free shuttle, shown outside the Caron Farmhouse, ferries visitors around Batoche National Historic Site/Jennifer Bain

More than 350,000 artifacts have been recovered on this site. Batoche’s modern visitor center sits on the edge of the historic battlefield. “Once you leave the visitor center, you can’t really see it while you’re on the site so as to not distract the modern from the historical,” explains Perret.

An open-air shuttle ferries visitors to key spots on the extensive grounds. On this September day, there are bales of hay everywhere and I learn that Parks Canada wisely contracts out the harvest rather than let the farmland sit unused.

Visitors gravitate to the rectory and church. The Métis were primarily Roman Catholic, Perret explains, and while the military planned to burn down the church, they relented and let it become a field hospital. It’s still an active church that can be rented for weddings and baptisms.

Look at the front of the rectory to see bullet holes from the Battle of Batoche/Jennifer Bain

The front of the rectory shows battle scars. “You can see a cluster of 13 to 15 bullet holes from the Battle of Batoche, depending on how good your eyes are,” says Perret.

Inside, she demonstrates Métis games — like ball and cup — that people played while waiting to see the priest. She dons a ceinture fléchée, the traditional arrowed sash of the Métis Nation, showing how these long red sashes could be become a belt, tie, back brace, sling, rope and baby carrier. "Every family had their own design and colors,” Perret notes. Upstairs, in space set aside as a post office, she proudly shows off a mail slot for her great-great-great uncle Barthélémi Pilon who took part in the resistance. Perret notes that he and her great-great-great aunt Christine were about her age when the events of 1885 took place.

Another Batoche highlight is the Caron Farmhouse, which shows what life was like for sociable Métis homesteaders Jean and Marguerite Caron as they farmed, raised children and hosted parties with jigging and fiddling. Perret explains that the sparsely decorated living room is “close to what it would have looked like in party mode." Parks Canada worked with the Gabriel Dumont Institute to gather information and artifacts for the home.

In the Caron Farmhouse living room, Parks Canada heritage interpreter Jacelyn Perret shows how it's ready for a party/Jennifer Bain

Sometimes you can rent canoes at Batoche, but today as it nears the end of the visitor season I’m only able to gaze at the South Saskatchewan River and walk down a few trails.

One short path leads to an eroding cliff overlooking the river, where Parks Canada has placed two of its red Adirondack chairs across the river from a large meadow where bison were once hunted. (The chairs, found at parks and sites across the country, encourage people to stop and take in views but also take photos and share them on social media. They're also made from recycled plastic diverted from landfills.)

As we try out the chairs, Perret makes sure we look up, down and across the river. “You can see why the Métis settled in this area and why they loved it so much,” she says. “And why they wanted to protect and preserve it.”

Sit in these Parks Canada red chairs for views of the South Saskatchewan River/Jennifer Bain

The Saint Antoine-de Padoue Cemetery, in the middle of Batoche, belongs to the local parish that owns the church. It dates back to 1881, has about 375 graves and is still active. “If you have a family connection to Batoche you can buy a plot,” Perret explains.

Many Métis and First Nations fighters who fell in the 1885 resistance are buried here. A mass grave marks the final resting place of nine Métis resistance fighters who were killed on the last day of battle. Dumont, who fled to the U.S. after the battle but was granted amnesty and retired in Saskatchewan, is buried here and a large rock monument honors his legacy as a buffalo hunter, founder of the St. Laurent community and commander of the resistance.

“He was my great, great, great, great uncle,” says Perret. “It’s a little distant, but still a nice connection to be able to talk about.”

The magnificent rock and plaque that marks the final resting place of Gabriel Dumont, a prominent leader of the Métis people/Jennifer Bain

For me, the most memorable part of Batoche is the East Village. Rather than recreate what was once the community’s business district, Parks Canada commissioned an exhibit on the landscape where important trade routes intersected and ferries helped people cross the river. The Carlton Red River Cart Trail Route was the most important overland trade route through 19th-century Saskatchewan, linking Fort Garry (Manitoba) with Edmonton House (Alberta) during the fur trade era.

First I pass a field with foundations of four buildings — Fisher’s Store, Boyer’s Store, Garnot’s “Stopping Place” and Xavier Letendre’s Store. A fence keeps people from getting too close, but fading interpretive signs help paint a picture of these merchants.

Then I arrive at a stunning viewing platform beside a trade route playground. Launched in 2016, the platform — made of two open and weathered Corten steel chambers attached by a slatted cedar stage — appears to float over the landscape. I climb the stairs into an open-air enclosure where a vertical opening from the floor skyward directs my gaze toward the hill and a viewing lens that frames Letendre’s famous Lot 47.

This East Village viewing platform is filled with interpretive panels and views of the river and former Métis river lots/Jennifer Bain

A sky-high timeline traces the story here from 1821, when the Hudson’s Bay and North West companies merged, to 2011 when the Canadian census reported 451,785 people who identified as Métis. Space at top of the timeline stands ready to mark the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Batoche in 2085.

If you don’t have kids, you could be forgiven for not walking over to the trade route playground. It serves as a three-dimensional scaled map, with trading posts and Métis communities identified by large upright log markers. It’s a vivid way to show how goods and people once moved between communities. Bright yellow panels provide modern recipes for traditional Métis meals including pemmican, Bannock, chokecherry syrup, bannock, Saskatoon crumble and hamburger soup.

An imaginative East Village playground at Batoche mimics trade routes/Jennifer Bain

You really need a full day to explore Batoche but my time is limited to several hours. I gulp down lunch, learning that the bison in my stew comes from Grasslands National Park. To keep the herd at a manageable number, Parks Canada “surpluses” some animals at auction and even keeps some meat.

While probing staff about plants and wildlife, I’m told to watch for turkey vultures and go to the gift shop for that book by the Gabriel Dumont Institute called Plants Growing Along the River: A learning guide for reconciliation through land, plants and Métis culture.

The guide shares the Métis relationship to 23 plants that are found at or near the community of Batoche. “Sustaining all life on the land, these plants provide medicines, food, tools, beauty, and recreation,” the book explains. The plant guide also serves as a response to Principle Eight from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Principles of Reconciliation of 2015 that says “supporting Aboriginal peoples’ cultural revitalization and integrating Indigenous knowledge systems, oral histories, laws, protocols, and connections to the land into the reconciliation process are essential.”

I learn that the Saskatoon berry tart I've just eaten for dessert is made from what the Métis call misâskwatômina in Northern Michif of lii pwayr in Heritage Michif. An Elder who contributed personal stories to the book explains that Saskatoons were usually sun-dried. But as “Road Allowance People” often forced to live on scraps of land intended for rural roads, the Métis lived between the main highway and dusty gravel roads to the lake. Métis children were often tasked with using willow branches to keep flies and dust off the berries as they dried.

The Saskatoon berry tart from the Batoche café is made with a local berry long loved by the Métis/Jennifer Bain

Margaret Harrison is one of the Elders who contributes stories to the plant guide. She grew up in Saskatchewan’s Katepwa Lake road allowance community in a landscape similar to what’s here at Batoche. She's also the key figure in the rug art display in the rotating exhibit space at Batoche today.

At the exhibt, I learn how many Métis women once picked and sold food, as well as decorative household objects, in the growing settler economy. They cut old clothes, burlap sacks and cloth rags into strips for rug making when they could no longer be worn. Braided rugs fetched a dollar or two, while hooked rugs earned three or four dollars. Some rugs were traded for butter, eggs and meat. they often featured a distinctive Métis rose pattern influenced by floral beadwork and silk embroidery patterns.

As I leave Batoche, I linger by a life-size cutout of Riel on the front lawn that bears his famous quote: “We did not rebel, we defended and maintained rights which we enjoyed and had neither forfeited nor sold.”

Nearby, the Canadian flag flies beside the Métis flag. This one shows a white infinity symbol on a blue background, representing the unity of two cultures and faith that the Métis culture will live on forever.

While You're In Saskatchewan:

At the Dakota Dunes Resort, Wyatt Brown does a pow wow dance presentation as Elmer Tutosis drums before we make bannock on the fire/Jennifer Bain

To visit Batoche National Historic Site and support Indigenous businesses, I stayed at the Dakota Dunes Resort outside of Saskatoon. The 155-room resort opened in October 2020 on traditional Whitecap Dakota Unceded Territory in the South Saskatchewan River Valley Basin. Angular window trims and exterior wood panels echo the traditional tipi. There’s a golf course, casino and Moose Woods Home Fire Grill. I had a chance to eBike to the sports grounds used by the Whitecap Dakota First Nation and sample some of the resort’s cultural experiences, including the bannock and bonfire program, pow wow dance presentations and Indigenous games session.

Not far from Batoche, I learned about the Battle of Duck Lake at the Duck Lake Regional Interpretive Centre. This area was the first battle site during the North-West Resistance, and the March 26, 1885 squirmish was a victory for the Métis resistance.

Add comment