A decade ago, driving out of Natural Bridges National Monument in southeast Utah, I looked up and remarked to my wife that the two peaks seeming to tower over us to the east were impressive. “Those are the Bears Ears,” she said. At that moment I was introduced to iconic landforms that have leapt to the American consciousness in an epic battle over how public lands should be used. Combatants include five Native American tribes and many factions in Utah and across the United States, but especially in Utah, and in San Juan County, Utah.

That trip was my introduction to the amazing natural landscape of southeast Utah, and to the archaeological treasures and deep prehistory and history of this amazing place. Five years later I had the great fortune to spend five days in what in late 2016 had become Bears Ears National Monument by President Barak Obama’s executive order using the Antiquities Act — our group’s two guides were rock art specialist Joe Pachak and historian and writer, Andy Gulliford.

The emphasis of the trip was rock art, but these two guys knew so much about the place that we not only saw many expressions of ancient peoples on the rock but climbed up and down into “cliff dwellings” and other places where the “Ancients,” as some call them, had lived over thousands of years. We gazed across deep canyons at structures built in alcoves in sheer cliffs where unavoidable questions arose about how and why these people lived in such inaccessible places. Our guides answered questions, explained archaeological theories, and encouraged us to come up with our own ideas based on what we were seeing. It was great fun, very informative, and I was hooked, so when President Donald Trump reduced Obama’s Bears Ears National Monument by 85 percent I was outraged and have been ever-more fascinated by the stories of this landscape.

Andy Gulliford, a professor of history at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado, is uniquely qualified to write this remarkable synthesis of the complex story of this place, a story ranging from Archaic prehistoric times to the present, or at least to 2021 when the Biden administration restored Obama’s Bears Ears National Monument. Gulliford has been exploring the landscape for decades. A prolific writer and researcher, he has delved into the Bears Ears story in the vast literature about it, by walking the landscape as much as possible, and by interacting with the many people who have pieced the story together and others who have been part of the story. With a home in Bluff, Utah, on the edge of Bears Ears, he knows the place and the people intimately. The time he covers is at least 11,000 years, and the space, while focused on Cedar Mesa and Bears Ears, ranges across the Four Corners, because what happened on and to the Bears Ears landscape and its people has been tied throughout to what was happening across the region from the Colorado River to the west and to the Rio Grande Valley in the east.

The organization of the book is chronological, beginning with Paleo-Indians stretching back to the Pleistocene, then “From Basketmakers to Ancestral Puebloans, AD 50-1150.” Gulliford takes us with him on jaunts across the Bears Ears region, explaining what is known from rock art and the archaeological record about how people lived for millennia. For example, a rock art panel near the top of Comb Ridge illustrates how, when drought led farm families to group together, their ceremonies became larger and more elaborate. “On a massive sandstone wall, 179 carved human figures march in three lines toward a circle that probably depicts a great kiva or underground ceremonial space. To stand before the Procession Panel is to feel the power of Basketmaker villagers coming together to dance, sing, feast, and become one.” He explains how Bears Ears was the northwestern edge of the Ancestral Puebloan world, the cultural capital of which many archaeologists believe was Chaco, and how the Bears Ears region shows Chacoan influences in great houses and roads.

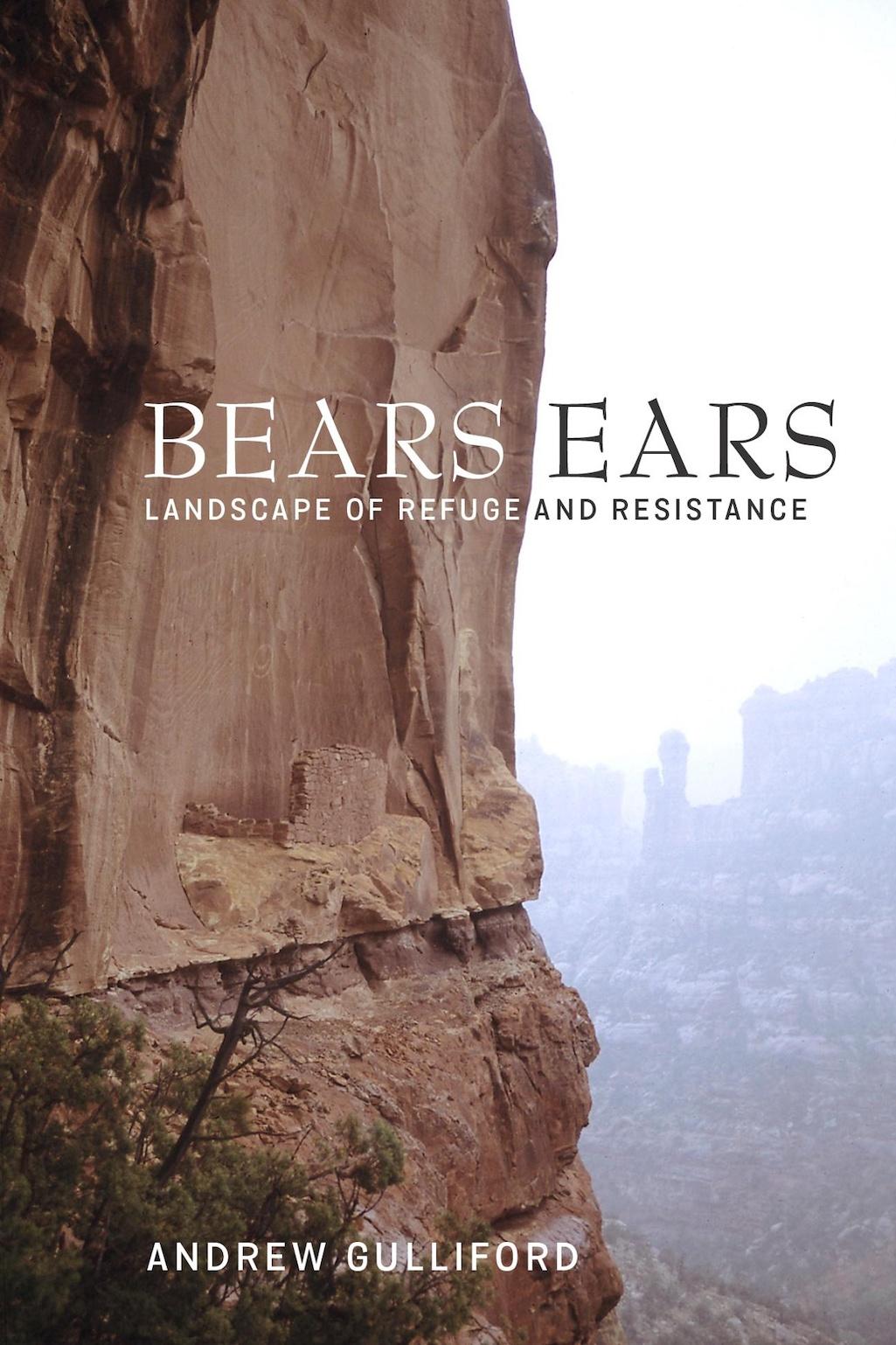

A photograph in the next chapter, “Into the Cliffs, 1150-1300,” also on the cover of the book, is of a defensive wall on a small ledge in the face of a soaring cliff, built in an astonishing location. How people got out there to construct this wall defies imagination, and rushing to it to defend against intruders seems hardly possible. Gulliford is quite a photographer and took this dramatic photo, undoubtedly at considerable risk just to get to such an aerie perch. After a brief overview of how and why people lived in the cliffs, ultimately abandoning the area because of drought and its many impacts on their society, he describes “Navajos, and Canyon Exploration, 1300 -1859.” The 1860s was a decade of American colonial expansion into the region, and the “Fearing Time” for the Navajo people whom the government forced into the “Long Walk” moving them from their land to incarceration at Fort Sumner in what is now eastern New Mexico. Many died, but some escaped into the Bears Ears refuge, an awful time for all Navajo, as for all tribes across the American West. He tells their story well, with an appropriate touch of outrage.

These early chapters are relatively brief, in part because the archaeological and historical records are relatively sparse. The next stages of the story are well documented: the incredible Mormon journey across the Bears Ears country to settle Bluff; cattlemen moving into the landscape, bringing impacts to a dry and fragile land; “cowboy archaeologists” like the Wetherill family raising concern about the looting of antiquities; and passage of the Antiquities Act in 1906. Nearly all land in Bears Ears was and is federal, and with the rise of conservation, the Antiquities Act, and federal land management agencies like the Forest Service, the presence of the federal government grew, much to the chagrin and anger of the Mormons who had “settled” the place. Clashes arose between the settlers and Indians, and between settlers and the federal government. The refuge theme of the book’s title was introduced with Ancient Puebloans finding shelter and safety in cliffs, and Navajos in remote canyons. The resistance theme emerges with Utes and Navajo people resisting government, settlers resisting both Indians and government, and government response to the entire situation.

In the 1930s, a large national monument was proposed that would have encompassed Bears Ears, but resistance to the idea prevailed, and over ensuing decades national monuments were established around Bears Ears, and then Canyonlands National Park, while Bears Ears remained unprotected from mineral exploration and mining, various Atomic Age impacts, and extensive looting of archaeological sites. The Antiquities Act had done nothing to protect what is sacred land for five Native American tribes in the region. Gulliford documents in detail the slow growth of concern about pothunting and other encroachments upon the values tribes had for this land. Legislation was passed to address the situation, and federal agents sometimes heavy-handedly enforced new regulations. Resistance to these federal actions from local communities who had come to consider pothunting or driving recreation vehicles across fragile land their right, objected in various ways, another episode of resistance in the story.

Ultimately, the tribes could no longer tolerate all of this, and surprisingly five tribes who had never worked together did so, and formed the Bears Ears Intertribal Coalition of Zuni, Navajo, Northern Ute, Ute Mountain Ute, and Hopi. They decided to use the Antiquities Act, a first for the Native American community, to protect part of their heritage. They drafted a proposal for a Bears Ears National Monument and proposed that this would be the first national monument with Native American co-management.

Gulliford explains what the tribes sought, quoting the Coalition’s rationale. “The Bears Ears region is not a series of isolated objects, but the object itself, a connected, living landscape, where the place, not a collection of items, must be protected. You cannot reduce the size without harming the whole.” Gulliford continues, writing that “[T]he struggle over Bears Ears is a contest over the soul of a landscape. Archaeologists claim that the Bears Ears area, as an ancient homeland for the Basketmaker and Ancestral Puebloan peoples, has cultural resources found nowhere else. Natural resources abound as well as scientific prospects. For Native people the goal is to make Bears Ears a living laboratory for the study and understanding of plants, animals, landscape, and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), which would be unique among all national monuments. Traditional knowledge would guide monument management and planning.”

The idea that the Bears Ears region is the “object” to be protected lies at the core of the tribal proposal, and the resistance to it. This monument proposal, and the crackdown on pothunting and locals collecting artifacts, has made southeast Utah a very contentious place. Gulliford notes that “Resistance of Natives to whites, whites to Natives, and locals to the federal government only intensified” after the federal government took some hesitant steps to protect archaeological and other resources. He describes the conflicts thoroughly in several chapters, a portrait of a complex clash of values. The land is simply a resource to many of the whites, but to most of the Native people, it is a sacred place where heritage lives and is stored and must be protected. The Obama monument, drastically reduced by Trump, was restored by President Biden, but the contest continues since the state of Utah in 2022 filed suit against Biden’s decision. While a federal district judge dismissed the state's effort, that ruling has been appealed to the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Bears Ears as “a vital new national monument” has much support in America, but the Utah state government hopes to challenge it all the way to the Supreme Court. Gulliford quotes High Country News about the Inter-Tribal Coalition: “The partnership demonstrated an unprecedented reliance on tribal consultation for the federal government. For many Indigenous leaders, it became a blueprint for how to involve tribes in the stewardship of lands that were originally stolen from them but are also important to the country as a whole.”

The saga of Bears Ears is quite a tale, well told by Gulliford. He is a scholar but also writes for a broad readership. His thorough documentation and citation of sources will satisfy his scholarly colleagues, and his telling of deeply human stories will captivate the rest of his readership. Historian colleagues might blanche at his inclusion of himself in the story, but the rest of us will be happy he has done so. His extensive personal knowledge of the place in its many dimensions — geological, archaeological, historical, anthropological, and even sociological — makes this the exceptionally compelling work that it is. Gulliford is not “siloed” in the academic compartments of the university part of his life, and this allows him to follow wherever the story of the land and its resources, natural and human, takes him.

Gulliford makes no bones about where his heart leads him after all this study and experience of the region — to protection of the Bears Ears landscape from miners and pothunters and other exploiters, and especially to protection of the Indigenous cultural values of the place. But he tells the story of those who oppose such protections in a way that allows us to understand why they feel as they do and have for more than a century. For instance, after the Mormons made their incredibly difficult Hole-in-the-Rock journey to colonize what is now San Juan County, Utah, they were not to be denied their rights to use the region as they believed they should, as farmers, ranchers, and in other ways. They established Bluff, and as Gulliford writes, “Bears Ears would become a landscape of resistance for Latter-Day Saints families just as it had been for centuries for Native inhabitants fleeing first the Spanish, then the Mexicans, and finally blue-coated American soldiers.” In doing so the Mormons pushed the around Natives without mercy, as Gulliford describes and documents in detail, so at least this reader has difficulty in sympathizing with many contemporary opponents of Bears Ears in southeast Utah. There is much discussion these days about systemic racism, and Gulliford does not use this term, but the story he tells surely seems an object example of precisely this.

This book is a must-read for anyone who is interested in the canyon country of southeast Utah. Hundreds, perhaps thousands, of books have been written about this remarkable place, but this one stands out in its comprehensiveness, a clear story line, and its remarkable blend of scholarship and strong personal perspective about a special place. I’ve often wondered why powers-that-be in Utah should be so dead-set against a Bears Ears National Monument (and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument) when the national parks of Utah, most of which evolved out of contested national monuments, have proven so economically important to that state. Why would they be so motivated to “kill the golden goose” of their park-related prosperity? This book does not provide the complete answer to this question but offers considerable insight. Most importantly, though, odd economics aside, Gulliford’s telling of the Bears Ears story makes a most compelling case that this landscape, while it should be protected for all Americans and the world for many reasons, should especially be protected as sacred land for Indigenous residents of the region who value it in so many deep ways. Protecting it will not be easy, and Gulliford touches on why this will be so, but for moral reasons, among others, we should try.

Postscript: On August 15, 2023. President Biden, using the powers granted him by the Antiquities Act, proclaimed the Baaj Nwaavjo l’tah Kukveni Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument. This monument was proposed by a large group of tribes called the Grand Canyon Tribal Coalition. Members of the Coalition include the Havasupai, Hopi, and Hualapai tribes, as well as the Kaibab Paiute Tribe, the Las Vegas Band of Paiute, the Moapa Band of Paiutes, the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, the Navajo Nation, the San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe, the Yavapai-Apache Nation, the Pueblo of Zuni, and the Colorado River Indian Tribes. Baaj nwaavjo means “where tribes roam” in the Havasupai language and I’tah kukveni means “our ancestral footprints” in Hopi. This national monument will protect 1.1 million acres surrounding Grand Canyon National Park from new uranium mining.

This is a big moment and testifies to the significance of the example and “blueprint” set by the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition. The Navajo Nation and Pueblo of Zuni are part of both coalitions, and the initiative and success of both coalitions suggests that tribes have found a way to redress some of the injustices to which they have so long been subjected. This is not, of course, a subject of Gulliford’s book, but learning of the new monument and the role of the tribes in conceiving and promoting it, immediately reminded me of the story he tells of Bears Ears, the injustices visited upon the tribes there, and their ultimate response with Obama’s proclamation of Bears Ears National Monument. President Biden’s proclamation reads in part:

The lands outside of the national park contain myriad sensitive and distinctive resources that contribute to the Grand Canyon region’s renown. In many of these lands outside the national park, however, the Federal Government permitted or encouraged intensive resource exploration and extraction to meet the needs of the nuclear age. For decades, the Tribal Nations and Indigenous peoples of the Grand Canyon region have worked to protect the health and wellness of their people and the lands, waters, and cultural resources of the region from the effects of this development, including by cleaning up abandoned mines and related pollution that has been left behind.

Much of the health and vitality of the Grand Canyon region today is attributable to the tireless work of Tribal Nations and Indigenous peoples, the lands’ first and steadfast stewards. In the tradition of their ancestors, who fought to defend the sovereignty of their nations and to regain access to places and sites essential to their cultural and traditional practices, Tribal Nations and Indigenous peoples have remained resolute in their commitment to protect the landscapes of the region, which are integral to their identity and indispensable to the health and well-being of people living in the Southwest.

The prominence of Tribal Nations and Indigenous peoples in his proclamation is telling. To fully understand the significance of this decision in 2023, read Gulliford’s book about Bears Ears. You will enjoy it and be richly rewarded with understanding of what all the fuss is about regarding national monuments in the Southwest.