Ranger Sarah Bachan reads "The Black Cat" in the cellar at Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site in Philadelphia/Jennifer Bain

“Do you all like spooky, scary stories?” ranger Sarah Bachan asks as we stand among the cobwebs in the cellar of the Philadelphia house where macabre literary genius Edgar Allan Poe once lived. “I assume you’re here because you do.”

We’re wrapping up a tour of Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site by listening to an abridged reading of one of the author’s greatest stories. Published in August 1843, “The Black Cat” follows an unnamed narrator who inexplicably tortures once-cherished pets and then murders his wife when she intervenes.

“I do want to warn you there are some depictions of violence towards animals and violence towards to humans in this story,” Bachan cautions the small crowd of adults and children. “And if it’s too much, or the setting is too much for you, I won’t be heartbroken if you do find you have a desire to leave.”

The cellar at Edgar Allan Poe's former house is empty except for cobwebs/Jennifer Bain

The brick and stone cellar is empty save for cobwebs I suspect are allowed to flourish to add to the atmosphere. Glimmers of late summer light come from two small windows and an exit sign that glows by the door.

The reading, Bachan explains, ties in with the way that people must use their imaginations to bring the mostly empty site to life. The story was published while Poe lived here with his cousin/wife, mother-in-law and cat, and was likely inspired by the house and its spooky cellar.

For 12 minutes, the ranger reads from a small book lit by the orange glow of a clip-on light. Behind her, a toy black cat with an arched back, open mouth and erect tail stands on a ledge in the remains of a false chimney once used to support the marble fireplace on the floor above.

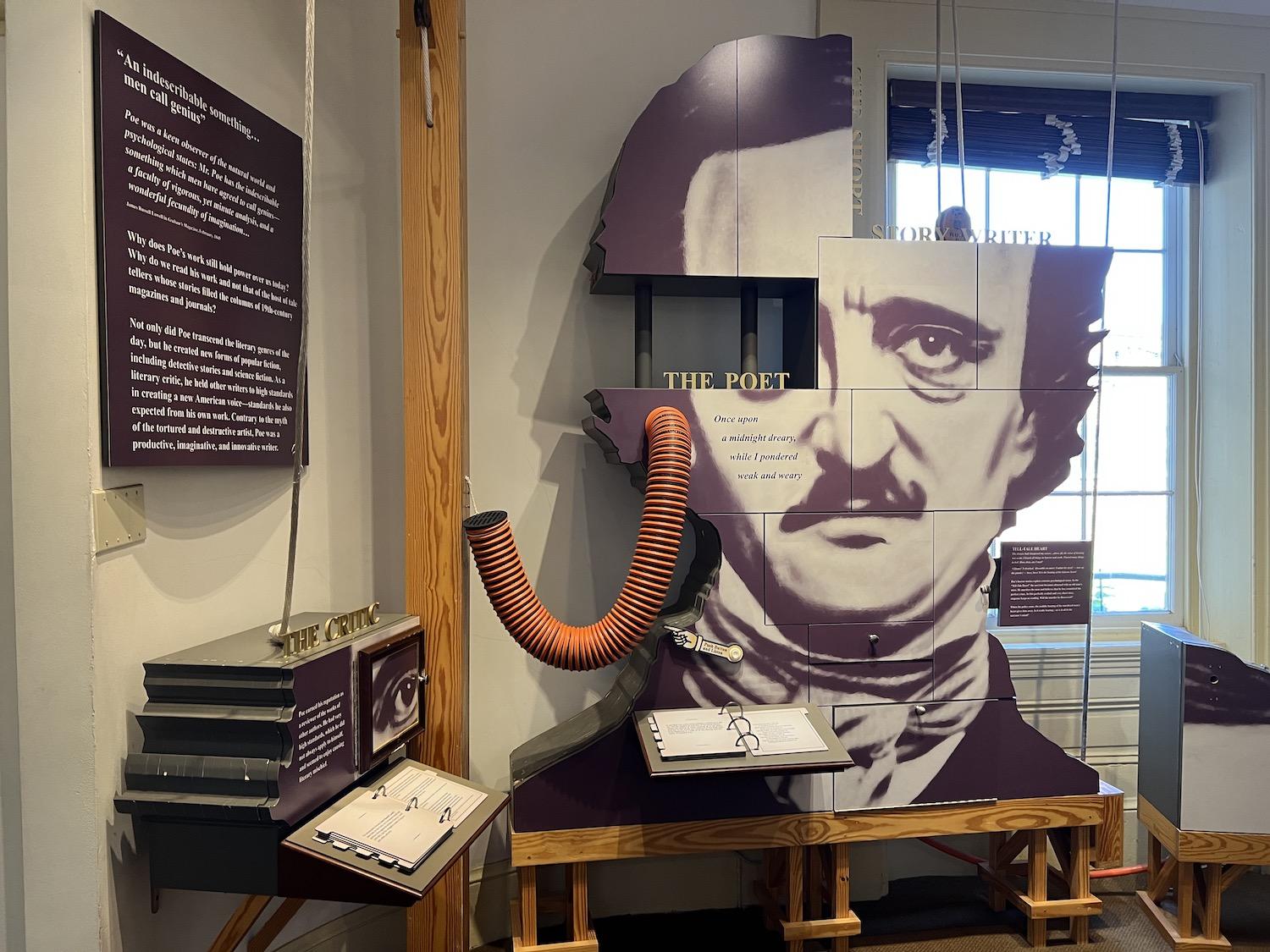

Part of the Poe House complex includes exhibits about the author's life and career/Jennifer Bain

The story famously climaxes when the cocky narrator shows police searching for his missing wife his basement. He doesn’t realize he has accidentally trapped his latest cat behind a brick wall with his wife’s bloodied corpse, and when it lets out a piercing screech, it exposes his crime.

“I had walled the monster up within the tomb!: Bachan ends with a theatrical flourish.

“So,” she continues, switching back to her natural speaking voice. “I want to thank you all for joining us through our little trip of imagination here at Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site. I hope that you’ll continue to explore Poe’s work and continue to use that imagination.”

An artist's rendering of how Poe House might have looked when Edgar Allan Poe lived in it/Jennifer Bain

Established by Congress in 1978, the site is managed by Independence National Historical Park and open Friday to Sunday.

Poe lived in five Philadelphia homes, but only this one at 532 N. 7th Street in the Spring Garden neighborhood survives. He rented it in 1843 and 1844 when it was a free-standing structure and when the city was one of America’s literary and publishing capitals.

“Philadelphia doesn’t get associated with Poe for whatever reason, even though it is the most prolific, productive time in his life,” muses Bachan. “That’s one of the biggest questions that we get. People are surprised that there’s (a) a park service site to Poe and (b) it’s in Philadelphia and not in Baltimore.”

This mural of Edgar Allan Poe is on private property a block away from the national historic site/Jennifer Bain

I arrive by Uber and the driver mistakenly drops me a block away in front of a mural painted on the side of a home that shows Poe, in a suit and looking sombre, alongside two lines from his story “Hop-Frog.”

I find my way back to the National Park Service site that we have driven right past. The unfurnished, three-storey brick house is the focal point. The complex includes north and south gardens plus the adjoining mid-19th century brick townhouse that serves as the visitor contact station and an exhibit space that explores Poe’s personal/family life and literary/publishing career.

Rather than restore Poe’s humble home, the NPS placed pictures by artist Steven Patricia on large canvases throughout the historic structure to give a general idea of how the rooms may have once appeared during his time here.

In a small second-floor room, a painting depicts Edgar Allan Poe writing alongside his cat/Jennifer Bain

Described by the NPS as “horrifying, mystifying, and full of genius,” Poe’s writing continues to impress the world. He “mastered the horror genre, using first-person narration and descriptive language to explore the intricacies of the human mind.” He wrote mysteries, introducing aspects that are now considered classic elements of detective fiction.

His classics include “The Gold Bug,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Fall of the House of Usher.” His poems include “The Raven,” “The Haunted Palace” and “To Helen.”

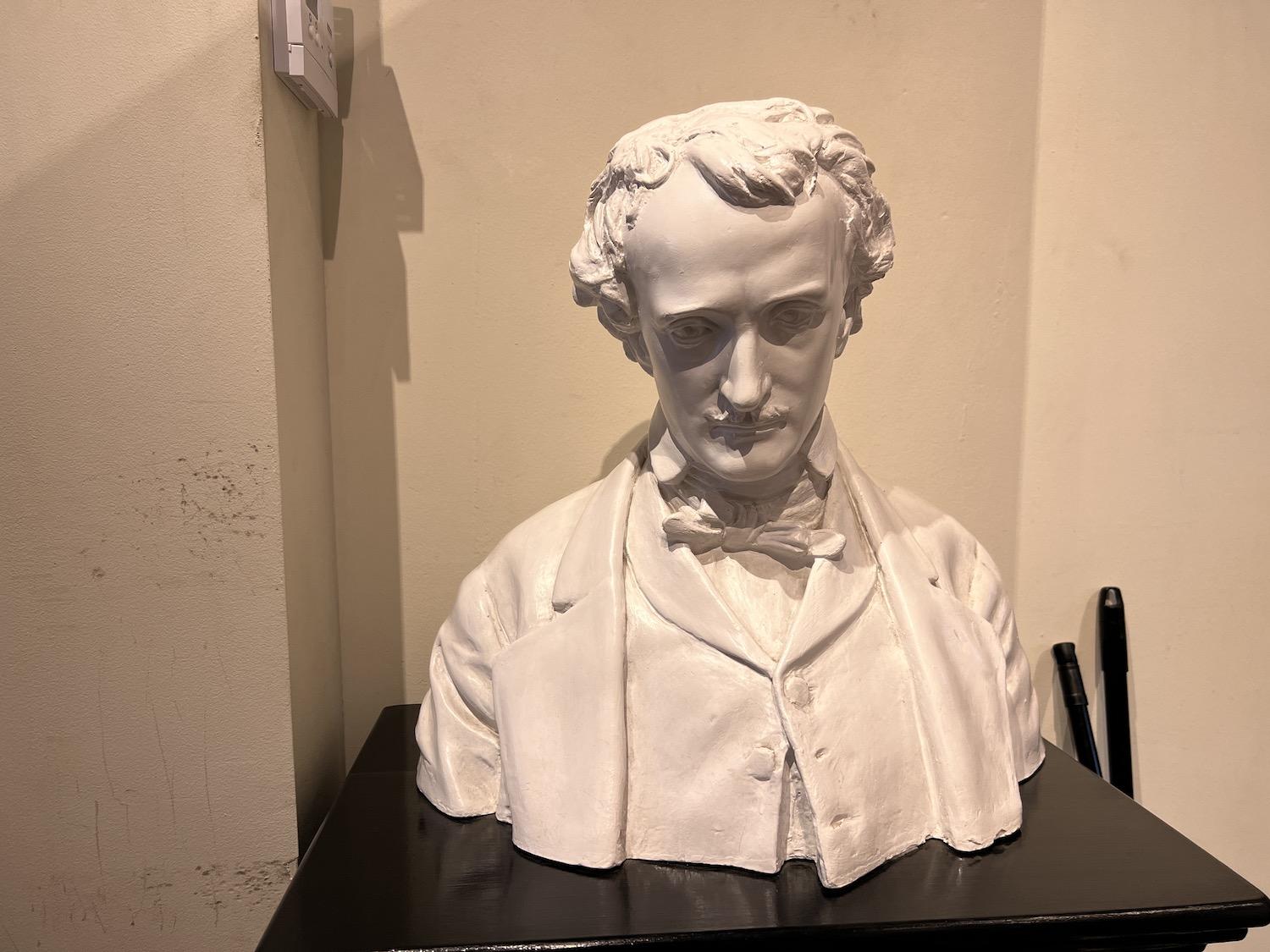

Poe was born in Boston in 1809 to two actors. His father abandoned the family, his mother died of tuberculosis and Poe and his two siblings were raised by different families.

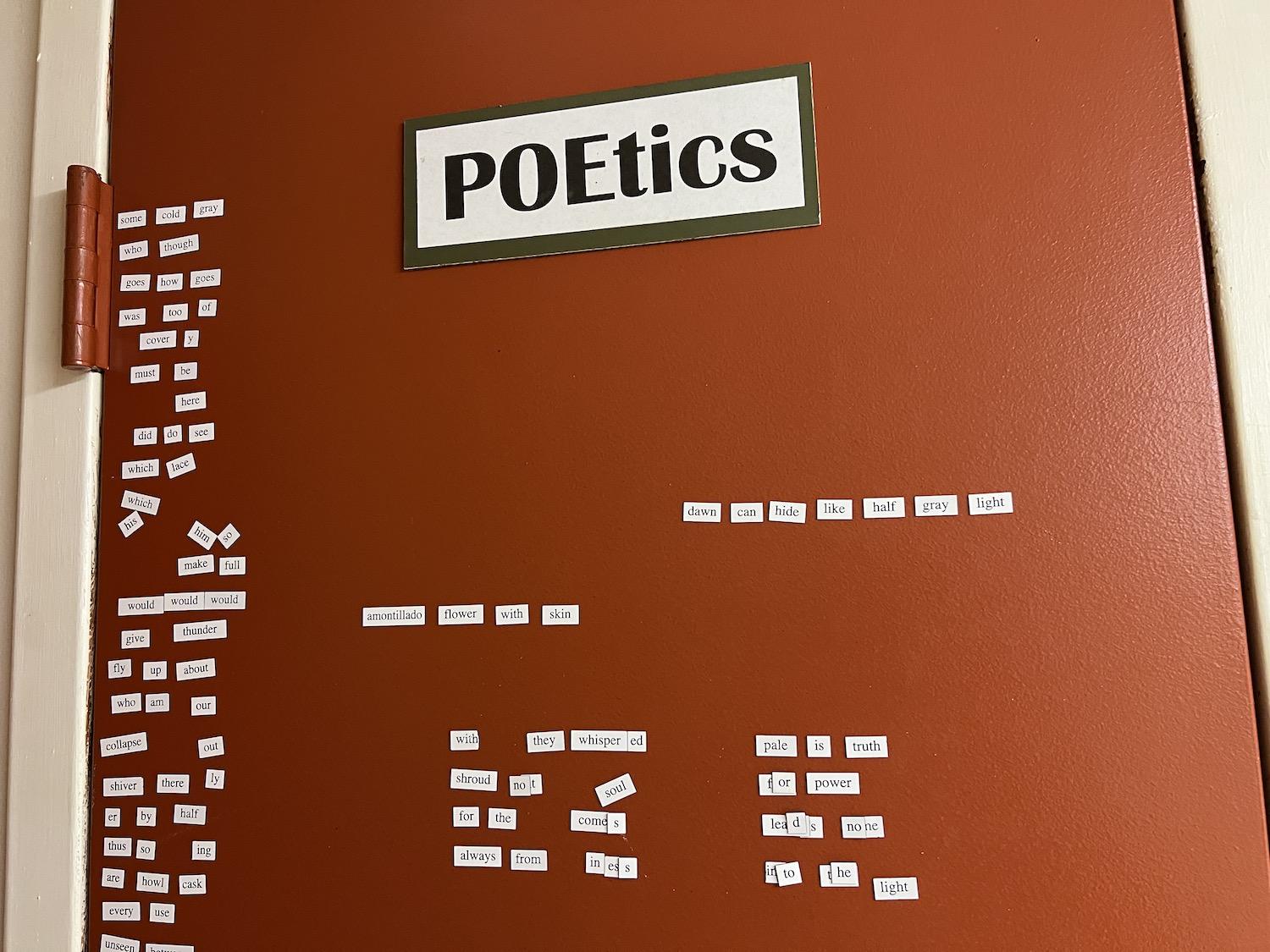

You can buy Edgar Allan Poe-themed magnetic poetry kits at the national historic site in Philadelphia/Jennifer Bain

Poe was taken in by Richmond merchant John Allan and his wife Frances, attending boarding school overseas and doing a short army stint. Eventually Poe moved to Baltimore to live with his impoverished Aunt Maria Poe Clemm (“Muddy”) and her young daughter Virginia. He married Virginia, his cousin, when she was 13 but she soon developed tuberculosis.

The family, which included Muddy, moved between New York City and Philadelphia as Poe struggled with Virginia’s illness, constant financial problems and depression.

In 1845, Poe gained his greatest fame as a poet after his poem “The Raven” was published and he briefly achieved his lifelong dream of owning a literary journal. But Virginia soon died and Poe then died mysteriously in 1849 of “acute congestion of the brain” while in Baltimore on his way to New York. He was just 40.

The Poe House complex includes gardens and green space/Jennifer Bain

“This was a happy space, I think,” Bachan says. “You can use your imagination here on what kind of space you think this might have been for the Poes. Of course, their life is highs and lows. They struggle with money. This is one of the nicer houses they lived in. Poe often struggles with thwarted dreams, ambitions — he can’t necessarily make the things he wants to make out of his career happen.”

Poe’s family — including a cat named Catterina — moved into this bright, airy house to help heal Virginia's lungs. It was new and they were the first people to rent it. There was a porch roof attached the exposed brick wall and a spacious lawn. The family was respected although some neighbors found them to be strange and insular.

You can watch a short film and then wander the house alone or take a guided tour.

With the help of art, you can imagine the time when this was Edgar Allan Poe's parlor, where the word "death" is etched on the wall by the door to the kitchen/Jennifer Bain

Tours begin outside and then move to the first floor parlor, where Poe tried to convince financial backers to fund his dream for a literary magazine. Since he moved frequently and lived beyond his means, he didn’t own much furniture — something that was revealed when he was forced to file for bankruptcy.

Perhaps the only elegant thing in the plain house was once a marble fireplace mantle in the parlor. Strangely, the word “death” is carved into the plaster near the doorway to the kitchen. While nobody knows if Poe made this carving, he was known to write and draw on walls in his university dorm room, so it is possible.

Like most middle-class households of Philadelphia in the 1840s, Poe’s house didn’t have electricity or running water. And since the family couldn’t afford domestic help, Muddy cooked on a wood stove, cleaned and cared for her ailing daughter.

What Edgar Allan Poe's kitchen may have looked like in 1843 and 1844/Jennifer Bain

The space is small and soon we climb to the second floor, where there's a room on each side of the stairwell.

One tiny room boasts a drawing of Poe at his writing desk with the family’s cat. This might have once been an open space and sitting area, but the wall was likely added by a later tenant.

Across the hall is Poe’s bedroom where he presumably slept alone because of his irregular writing hours and need to avoid contracting TB from his wife. While Poe was seen as "a dark and brooding man, his home was light and airy, his room was meticulously tidy and he had a personal affinity for neatness," according to the NPS.

Finally, we climb to the third floor for a quick look at Virginia’s and Muddy’s rooms, before exiting through a back porch to see where laundry and outdoor summer cooking were done, and then heading to the cellar for the reading.

In contrast to the unfurnished former home of Edgar Allan Poe, the "Reading Room" in an adjoining building has been furnished in honour of one of his fictional essays/Jennifer Bain

Once the tour is done, I linger over the exhibits, and in the Reading Room, a space with elaborate furnishings based on Poe’s fictional essay, “The Philosophy of Furniture.” It's here where you can attempt to write a scary story in two sentences, or a haiku — a poem with three lines.

This house was saved by voracious book collector Richard Gimbel, son of a department store magnate. The Richard Gimbel Foundation for Literary Research developed it into a historical park and eventually turned it over to the NPS. The rest of Gimbel’s Poe collection was given to the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Before leaving, I spot three kids from the cellar reading turning in their junior ranger booklets, reciting a NPS pledge and receiving badges. “I promise to protect and explore my national parks — national, historical and literary,” they chant after Bachan. ”I also promise to tell my family and friends about my time at Edgar Allan Poe National Historic Site. And I also promise to be nice to all the black cats I meet.”

David Caccia's sculpture of a raven casts a shadow over Edgar Allan Poe's former Philadelphia home in certain light/Jennifer Bain

I head outside for one last look at another black creature that's always associated with Poe.

Poe’s famously eerie poem “The Raven” — about a distraught lover and an antagonistic talking raven that repeats the word “nevermore” — was published on Jan. 29, 1845 in the New York Evening Mirror. Some believe it was written while he lived in Philadelphia, and the timing certainly makes sense.

An oversized raven sculpted by artist David Caccia from bronze and painted black sits atop a 12-foot pedestal in the yard, its wings outstretched to cast an eight-foot shadow on the south side of the red brick house and providing a hint of the genius that once unfolded behind closed doors.

Writer Edgar Allan Poe died a mysterious death in Baltimore when he was just 40/Jennifer Bain