There has been an effort to rename a mountain near Yosemite National Park for long time ranger/naturalist and Yosemite legend, Dr. Carl Sharsmith. I've asked Bill Jones, the lead member of the 'Name4Carl Committee' to provide for us an update on their efforts. Thanks for the wonderful article Bill. ~ Jeremy

YOSEMITE’S SHARSMITH PEAK NAMING STALLS: a status report from the Name4Carl Committee

Proposing Sharsmith Peak

Since at least 1976 an attempt has been made to formally establish the name Sharsmith Peak on a Yosemite National Park summit. In 2003 a group of citizens formed the Name4Carl Committee to complete this task. The federal naming process is prescribed by the Board on Geographic Names of the U.S. Geological Survey and if successful results in use of the name on federal maps and in federal publications.

But today the proposal is stalled.

Is it time to take a new approach?

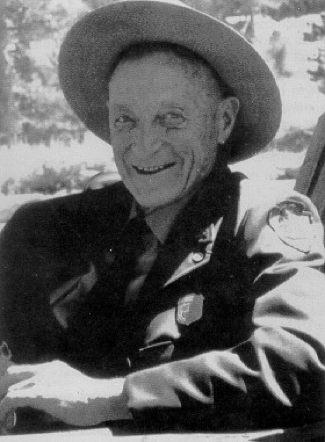

Dr. Carl W. Sharsmith (1903-1994)

The significance of the life of Carl Sharsmith was that he engaged an estimated 75,000 park visitors over his lifetime as an outdoor educator and park ranger-naturalist, serving in the Tuolumne Meadows region of Yosemite National Park. Within virtually each person he met, he instilled a life-long passion for the wonders of Yosemite's high country. He was beloved by the tens of thousands to whom he presented his philosophy and knowledge of nature and he also came to be known nationally as an example of professional interpretation at its best.

Carl was the only ranger naturalist at Tuolumne Meadows from 1931 until 1946. For his work after completing 25 seasons at Tuolumne Meadows, in 1956 he received the Department of the Interior Meritorious Service Award, the highest award the department can bestow on an employee. In 1981, after completing 50 seasons of service, he was the first to receive the Yosemite Award. He continued his passion to work as a park ranger-naturalist at Tuolumne Meadows for 63 seasons, including the summer of 1994, just weeks before his passing at the age of 91. That season he was celebrated as the oldest ranger in the National Park Service.

Carl started the plant herbarium at Washington State University before coming to San Jose State University and establishing an herbarium there, becoming Professor of Botany. Long after his retirement from teaching in 1972, he continued to work at his herbarium. Carl archived much of the High Sierra flora in his plant collections, including the naming of Hackelia sharsmithii. His herbarium contains 15,000 specimens and carries his name. Carl taught several thousands of students the science of botany, plant geography, and plant taxonomy. Many of his students went on to become educators themselves. Some became professionally engaged in research in the environmental sciences. Others became managers and stewards of public lands and/or engaged in conservation activities. Because of his excellence it "was always known" his legacy would some day be recalled by a park peak that would bear his name. Earlier, promoters hoped to get the naming job done while Carl would still know of it.

Background of the naming effort

Over the years a variety of peaks has been considered to become Sharsmith Peak, and at least by 1988 the effort began centering on a summit at the eastern border of the park, and the effort to name that was entrenched by 1991. That summit remains the focus of the naming effort, for it was the last one to be considered before Carl’s death, it is in the High Sierra area he loved and made loved, and it is an alpine area where his special alpine plants nestle among rocky slopes above the treeline, an area reached only by hiking. Now over 100 individuals and organizations have formally endorsed the naming. Included among them are persons with experience as rangers, naturalists, park administrators (even two national directors, 2 regional directors, and 5 Yosemite superintendents ), geologists (even a past director of the U.S. Geological Survey), professors, writers, artists, historians, conservation leaders, mountaineers, native Americans, medical doctors, and enthusiastic park visitors. Dr. Michael Adams, son of landscape photographer Ansel Adams, states his father would have endorsed the naming. (Ansel and Carl used to speculate who would have a peak named for him first; Ansel won with Mount Ansel Adams in 1985.) Several regional organizations endorse the naming, including the park’s long-time cooperator since 1923, the Yosemite Association with over 10,000 members. There has been one formal dissent from an individual.

Status

So what’s the hang-up? To get the naming done, the Name4Carl Committee researched the history of the naming effort, considered the various candidate peaks, and evaluated candidates with the criteria for naming used by the Board on Geographic Names. The Committee sent its formal proposal to the board last January 9. The board then began its own evaluation, seeking input on the proposal and especially from local interests, including Yosemite National Park, Inyo National Forest, Mono County, Tuolumne County, the California Advisory Committee on Geographic Names, and local Indian groups.

Mono County supported naming Sharsmith Peak, the California Advisory Committee on Geographic Names recommended against approval. The other local entities, to the knowledge of the Name4Carl Committee, have remained silent, with the Board awaiting their input.

Naming considerations

The California Advisory Committee found the proposed naming to conflict with the policy of not adding new names within wilderness areas. Such policy is that of both the U.S. Board on Geographic Names and the National Park Service. But Sharsmith Peak is at the edge of wilderness, straddling the Yosemite National Park/Inyo National Forest border with designated wilderness only on its west. Elsewhere along the park/forest border wilderness occurs on both sides of the line. Thus the Name4Carl Committee feels the present peak proposal is the best fit within the constraints of the policy and the appropriateness of the terrain to the man. Too, wilderness naming policy allows for exceptions to be made and names to be added if there are safety, administrative, and educational considerations. Because Sharsmith Peak has also been called other names (Peak 12,002, False White Mountain, and False White), selecting the single name Sharsmith Peak, which is already supplanting the others, would be advantageous in the event of a rescue situation. (Such occurred when a plane crashed there, and there is backcountry skiing on the peak’s slopes as well as summertime hiking.) Administration would be simplified with only one name. Education would be served by remembering the dedication of this man to understanding nature and spreading appreciation for it, which would serve to inspire future folks to strive to similar lofty goals. By honoring Carl, we also honor the profession of outdoor education. The merits of naming a peak for the man and his accomplishments have not been an issue. Thus there is adequate flexibility within the naming policy to allow bestowing the name Sharsmith Peak. For instance, Mount Ansel Adams received its formal name even though at the time it was surrounded by legislated wilderness (and to show other exceptions are possible to naming criteria, Mount Ansel Adams was named in 1985 shortly after Adams’ death in 1984 as an exception to a naming policy to wait at least five years after a person dies.)

How can the naming happen?

At this time approval of the naming by the Board is “iffy” at best. To improve the odds, supporters can send emails to [email protected] or signed hard-copy letters (preferred) to:

Mr. Lou Yost, Executive Secretary

Domestic Geographic Names Committee

U.S. Board on Geographic Names

c/o U.S. Geological Survey

523 National Center

Reston, Virginia 20192-0523

For further background on the naming proposal, see the Name4Carl Committee’s website www.name4carl.org; a sample letter to the naming board is included. Also there are copies of supporting statements and a summary of them. Supporters should address not only the contributions of Dr. Sharsmith and the appropriateness of this peak to bear his name plus the usage to date of his name on this peak, but also of the need for a single name for the peak, and that the naming board should use the available flexibility in the wilderness naming policy. The Name4Carl Committee (addresses below) would appreciate receiving a copy of letters for posting on their website.

The Name4Carl Committee welcomes further publicity on the naming proposal and notes that the Sharsmith Peak name is now favored even by those formerly using other names for the peak. This is important in that the naming board may be more likely to approve the naming as the peak is called Sharsmith Peak more by the public and in media. Currently searches on the websites Google Earth finds the name and Wikipedia defines it. The name was used in print at least as early as 1995. Although publicity may bring forth opponents to the naming, experience has shown vastly more would support the proposal.

Redirection of the naming effort

In this naming effort a gulf has developed between our government and its citizens. Because many of the proponents of the naming have wide experience in wilderness matters it is clear there would be no fundamental compromise in values should the naming occur. Yet advocates are presently stymied, and their wish may not be granted through the normal administrative process. Thus it is time to use other means to achieve this noble aim: legislation in the U.S. Congress would give the correct guidance to the Board and direct the naming. U.S. Representative Lois Capps of California has endorsed the naming as has Colorado State Representative Andy Kerr. More legislative support is sought, and a bill needs to be drafted, introduced, passed by Congress, and signed by the president. Because the present Name4Carl Committee is composed mainly of persons from other states who would be less effective in working with state legislators, Supporters in California are now solicited to form a group of constituents to have legislators that represent the region of Sharsmith Peak respond to this need. Contact the committee below to join.

Name 4 Carl Committee: Bill Jones, Bob Barbee, Bryan Harry, Len McKenzie, Wayne Merry, Jack Morehead, Owen Hoffman, Bob Fry, Douglass Hubbard, Allen Berrey, and Bill Wendt.

Bill Jones, lead member

Name4Carl Committee

0637 Blue Ridge Road

Silverthorne, CO 08498-8927

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.name4carl.org

Comments

Yes, the old ranger, the oldest active ranger in the National Park Service during his tenure. I knew him like an old pipe...I can still smell that half/half pipe tobacco coming from his rustic cabin at Tuolumne Meadows. God, this guy was a real trip to hear his fabulous stories what the real Yosemite was like, back in the days when nature was crisp and raw with adventure. No super lite equipment or special fitting clothes to combat the elements of nature. Old Carl was a champion of resourcefulness, never wasted much of anything, but gave us profound wisdom of the wilderness in his many wonderous nature hikes through the mighty Sierra's...and never forgetting Tuolumne walks. He was a master botanist with a keen eye for nature and a sharp wit to match. Naming a peak after old Carl wouldn't matter much, one way or another. For gods sake, this old ranger didn't want to be canonized into the mountain, just name it and be done with it...or just name it: Carls Peak and keep it simple...that's the way Carl would like it and with a bit of resourcefulness. Yes Carl, I know and can remember that flower, it's the Twin Flower, or the Linnaea borealis! Yap, great teacher at state!

Now for the dissenting opinion. Regardless of the stature of the man in his service to the park, I feel it the height of pretenctious, arrogant, self-serving behavior to connect a human name with the wonders of the natural world. It's a showboating way to immortalize a common human being. And the sorry fact is we, the human species, are quite common is all respects. Rivers, lakes, mountains, oceans, and the other physical features of the environment should be left out of the naming discussion. This isn't a slight against Dr. Sharsmith. I know not the man or his reputation. But I can say the same about Zeb Pike, and I was never crazy about his personalized peak either. Ditto Bill Williams. And a host of others I need not name. You want a monument to the man, fine I say. Take up a collection and bronze the old bugger right outside the visitor's center, replete with full NPS regalia. Give him a nice plaque too. Plant a tree, erect a bench, cultivate a flower garden. A mountain simply isn't befitting as a "memorial" to any one person. Denali, Navaho, Red, Whitewater Baldy, Quartz, Kings, Desert.......there's some good monikers for mountains. At least in some fashion they lend a descriptive character to the landscape. Attaching a human lineage to natural phenomenon cheapens the entire package. I'll send the first dollar to start the fund in anyone cares to undertake the task. But I'll be monitoring the progress of the program with a shyster ACLU lawyer in my pocket, just in case!

To me, Dr. Carl W. Sharsmith was no mere mortal. He is an integral part of Yosemite's history. His Yosemite legacy stands with that of John Muir and Ansel Adams.

However, unlike Muir and Adams, there is not a wide-spread collection of published works or photographs. Instead, there are an estimated 75,000 individuals whose lives he touched as a park ranger-naturalist, and thousands more as a professor and botanist, providing for memories and personal experiences that will last far beyond a human life-time.

By honoring the man, we also honor the profession of outdoor education in our national parks. The process of naming a peak to commemorate the man and his accomplishments began well before this region was formally designated as Congressionally established wilderness. In 1984, when the Yosemite Wilderness was formally established, Carl had completed his 53rd season with the NPS and was in his 82nd year of life.

After Congressional establishment of the Yosemite Wilderness, Carl continued serving the NPS and the park visitor for another ten years (including his final season of 1994 in Tuolumne Meadows at the age of 91)!.

At present, Sharsmith Peak is the name for this feature used locally by hikers, skiers, and naturalists. It has been in local use for more than a decade, if not longer. Officially, the peak is unnamed. It is located on the eastern edge of the park in which Dr. Sharsmith spent 63 seasons introducing park visitors of all ages to the virtues of the Range of Light.

If you would like to take a walk with Carl today, read his 1957 Yosemite Nature Note at

http://www.yosemite.ca.us/library/yosemite_nature_notes/36/36-9.pdf

or visit

www.name4carl.org

for additional information about the man, his legacy, and the effort to support the naming of Sharsmith Peak.

Owen Hoffman

Oak Ridge, TN 37830

While Dr. Sharsmith was definately a great and influential person for Yosemite, I believe that this choice of peaks should be looked at, with regard to its history. In naming a peak, the history of the mountain itself should be evaluated, as well as Dr. Sharsmith's direct relationship to this peak, and compare this with the contribution of others/groups. I specifically would like others to compare the meaning and history of this peak with regard to Dr. Sharsmith to that of the Search and Rescue team, and both's influence in Yosemite and the area.

Here is a little history of this specific mountain.

Although there is no easy way to compare rescues, it is debatable, but also likely, that on January 8, 1982, the most difficult, dramatic, improbable yet successful rescues in the history of the entire National Park System occurred on this mountain.

On January 3, 1982, an airplane I was in crashed onto the peak in the worst storms in recorded history of the area. Five days later, after extreme heroics of many people in a combined search and rescue effort, (six people knowingly and unquestionably risked their lives), I was successfully rescued. A listing of the people who risked their lives and their accomplishments are detailed below. On January 5, 1982, (day 2 f the search) the highest snowfall amount in history of Yosemite Valley occurred, which was 29.5 inches in a 24 hour period. This peak is higher and received even more snowfall.

Chas and Anne MacQuarie: This husband and wife team were back country rangers at Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite for many years, including 1982. Due to poor weather (blizzard) conditions, the first few days of the search were limited to ground crews. Chas and Anne hiked through the blizzard, (the worst storm in recorded history of the park) and waist deep snow in order to open a closed ranger station which helped the search. It took them all day, from sunrise to sunset, to reach this closed ranger station, which was only one mile away.

On the 5th day of the search, the crashed plane was found by the NAS Lemoore Search and Rescue. Due to the steepness of the peak, the amount of snow (called loaded), and the high probability of an avalanche, the helicopter could not land anywhere close to the crash location. Chas and Anne were picked up, and dropped on the closest ledge to the crash site. This ledge was so small that the helicopter could do a one-skid landing, which was extremely difficult considering the conditions and size of the ledge. In their progress to the plane, they encountered an avalanche crack, which is where the snow has started to avalanche and then stopped. This is a sign of a very unstable slope and likely could avalanche at any moment. Anne stayed above and belayed (anchored with a rope) Chas who proceeded to the plane. If the slope avalanched, Anne could keep Chas from being caught in the avalanche. When Chas reached the plane and determined there was a survivor, Anne disregarded both their personal safety and climbed to the plane to help Chas dig enough snow to provide an exit for me from the plane and also supported the rescue efforts of the Navy helicopter crew on the ground. Once I was secured to the helicopter in a heroic rescue, they were left on the mountain to ski their way back to the ranger station (many miles away) due to my condition. With the helicopter going to the hospital, there was no time to return for them.

Daniel Ellison: The Navy helicopter pilot stationed at NAS Lemoore who expertly flew the helicopter which not only found the plane, but also conducted the impossible rescue. In an amazing feat, Commander Ellison hovered the helicopter, low on fuel, at altitude, in severely gusting winds, and in a white-out without visual reference for over ten minutes in order to perform the rescue. This was the only way possible. It was his sure skill and ability, combined with the help of his crew, that kept the helicopter from crashing during the rescue. Commander Ellison earned and was awarded with the Distinguished Flying Cross, in peacetime, for this feat. This award is extremely difficult to earn in war-time, and even harder in peacetime.

The criteria for the Distinguished Flying Cross are:

The Distinguished Flying Cross is awarded to any person who, while serving in any capacity with the Armed Forces of the United States, distinguishes himself by heroism or extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight. The performance of the act of heroism must be evidenced by voluntary action above and beyond the call of duty. The extraordinary achievement must have resulted in an accomplishment so exceptional and outstanding as to clearly set the individual apart from his comrades or from other persons in similar circumstances. Awards will be made only to recognize single acts of heroism or extraordinary achievement and will not be made in recognition of sustained operational activities against an armed enemy.

Gerald “Jerry” Balderson: Crew Chief Balderson was the person who spotted the plane (contrary to the Chronicle article of 11-28-07). Chief Balderson risked his life when he was hoisted down to the plane to rescue me. He worked in a blizzard white-out condition caused by the loose snow blown into the air from the helicopter’s wash. There have been two accounts as to the temperature, one being negative 40 degrees and the other being negative sixty degrees. To the human body, there likely is not that much of a difference between -40 and -60 degrees. Due to the avalanche conditions, Chief Balderson was not allowed to detach himself from the cable during his ground work. If the hillside avalanched, being tethered to the helicopter would limit the likelihood of his death, while greatly increasing the likelihood of the helicopter crashing. Due to the gusting winds and difficulty in the hover, the helicopter moved up and down during the rescue. When the excess slack in the cable came off of the snow, a huge static charge created by the helicopter’s rotors exhibited on Chief Balderson. This occurred many times. In his duties, Chief Balderson kept a watchful eye on the cable in order to make sure that he was not touching me when the cable left the ground and absorbed the shock completely himself. In my extreme hypothermic condition, the static shock would have unquestionably killed me outright by causing a heart attack.

For his efforts, Chief Balderson earned as was awarded the Navy Marine Corps Medal, which is the second highest peacetime award by the Department of the Navy. In order to earn this medal, it must be clearly shown that the action was done with an unquestionable and high risk of one’s own life. The requirements are:

Awarded to any person who, while serving in any capacity with the U.S. Navy or the U.S. Marine Corps, distinguishes himself/herself by heroism not involving actual conflict with the enemy. For acts of lifesaving, or attempted lifesaving, it is required that the action be performed at the risk of one's own life.

Reg Barnes: During the rescue, Second Crewman Barnes completed the tasks of what two crewman would normally do. He not only expertly operated the hoist, but also acted as the visual eyes for the pilot in determining the position of the helicopter with regard to the mountain. Due to the direction of the very gusty and steady winds, the helicopter was forced to hover with the tail pointing toward the steep mountain. Second Crewman Barnes was the only person who could see how close the tail and its rotor was to the cliff, and relayed this information to the pilot, while also telling the pilot if there was slack in the cable to Chief Balderson by the feel of the tension in the cable. Due to the steepness of the mountain, the hovering helicopter was always dangerously close to the sheer cliff.

For his efforts, Second Crewman Barnes earned and was awarded the Air Medal. The requirements for the Air Medal earned in an individual act are:

Individual Award. Awarded to persons who, while serving in any capacity with the Armed Forces of the United States, distinguishes himself/herself by heroic/meritorious achievement while participating in an aerial flight under flight orders. Awards may be made for single acts of meritorious achievement, involving superior airmanship, which are of a lesser degree than required for award of the Distinguished Flying Cross, but nevertheless were accomplished with distinction beyond that normally expected.

Dave Urban: Lieutenant Urban was the co-pilot of the helicopter during the search and rescue. Due to his position in the helicopter, he conducted the one-skid landing on a small ledge on a steep cliff near the top of a mountain in order to allow the ground rangers, Chas and Anne MacQuarie, to disembark and proceed to the crashed plane. Due to the severity of the gusting winds, this was a very difficult one-skid landing.

For his efforts, Lieutenant Urban also earned and was awarded the Air Medal.

Besides the heroics of the above people, all of which unquestionably risked their lives to save me, another very instrumental person in the rescue was Mr. John Dill of the Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR). Through his lifetime of rescue work, Mr. Dill has earned a mythical status among the search and rescue community. Words cannot adequately describe his abilities to understand the behavior of people and apply that with his knowledge of the terrain and conditions in order to locate missing people. With my rescue, Mr. Dill used the data provided, figured out which data was incorrect, and was able to pinpoint the probable location of the plane to a very small and precise area. In this small area, the helicopter crew was able to concentrate their search efforts to find a white plane with a brown tail buried under the snow with only the smallest of pieces being visible. The visible section of the plane was approximately two feet by three feet, while the search area was hundreds of square miles. It was Mr. Dill’s ability to limit the search area to the highest of probability areas that allowed the crew to be able to concentrate on such a small area and quickly observe such a small piece of the crashed plane.

I also believe that it should also be noted that my survival also was above and beyond expectation. To survive an airplane crash, be stranded inside the small plane for five days, buried in snow, in sub-zero temperatures and with your dead mother and stepfather is not a normal everyday occurrence. When rescued, my body temperature was 84 degrees and wearing a T-shirt and long underwear, with my pants were frozen to my ankles. However, the crew managed to safely rescue me.

Further, after my rescue, the Mono County Sherriff’s office risked their lives on the same avalanche prone slope a few days later to remove the bodies of my deceased mother and stepfather.

While I greatly believe that this White Mountain should be re-named, I would be hopeful for you to look at the history of the mountain and all of the risks and sacrifices made there in order to determine what the most appropriate name should be. Not diminishing the greatness of Dr. Carl Sharsmith and his influence to the general area, I believe that the name of the mountain should reflect all that occurred on the specific mountain. I believe that “Rescue Mountain” or “Rescue Peak” would be more appropriate. However, should Dr. Sharsmith have a direct link, history, or contribution directly that overshadows the efforts of the Search and Rescue crews, I would appreciate this being demonstrated.

It should be noted that “Rescue” is appropriate to demonstration the appreciation of the Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR) organization. YOSAR is considered one of the best SAR teams in the world and since its inception in the 1960’s, responds to approximately 200 calls per year. The team is mostly composed of volunteers, which shows their true dedication to helping others above themselves, and thus a more meaningful tribute is necessary. These people willingly and knowingly risk their lives for others in the harshest of conditions. The SAR group at NAS Lemoore also did many heroic rescues in the entire are of Central California.

There are many reference newspaper articles that I could provide you should you desire. While the survival and rescue made national headline news, some of the articles are:

SF Chronicle, Page A1, January 9, 1982

SF Chronicle, Page A1, January 10, 1982

Fairfield Daily Republic, A1, August 19, 2007

Helena Independent Record, Page A1, October 14, 2007

SF Chronicle, Page A1, November 25, 2007

I'm with Lone Hiker. I don't doubt he was a great man, but we should not be naming natural features after people. Name a ranger station or BC cabin for him, but not a peak.

What will we do when we run out of things to name? Take his name off to put a more recent one on?

Some of you might remember Larry Nahm, one of Yosemite National Park's first librarians. Larry worked with many of us who had the privilege of residing in Yosemite during the early 1970's. I just received the following account from Larry of a recent hike he took up to the summit of Sharsmith Peak on the eastern border of Yosemite, and have received his permission to share this account online.

[Note Larry's reference to Yosemite's legendary seasonal ranger-naturalists of former times.]

It was a good, leg-stretching ramble yesterday to the top of Sharsmith Peak with the Bristlecone Chapter of the Ca. Native Plant Society. Leader Cathy Rose, as always, performed splendidly telling stories, evoking memories of Carl (and Will Neely and Bob Fry en passant). Ivesia, Lemmon's paintbrush, rock fringe, sorrel and alpine gold were among many species still abloom. We saw several of the endangered pikas and frogs. Marmots, reportedly, had a day or two earlier settled in for the winter; none were heard or observed. A prairie falcon, harassed for an instant by a smaller bird, zoomed out of sight. Twelve folks made the saunter, but three stopped short of the summit. A sextet from the Yosemite Association passed us, and summitted first.

I rest sore muscles today, and recall the greater energy enjoyed back when....But the salubriousness of the alpine air, of the alpine ethos--it seems undiminished.

Enjoy summer's remains.

Larry

As a former ranger in Yosemite and the Tuolumne Meadows Sub-district ranger during some of Dr. Sharsmith's legendary service as one of the finest interpreters I have ever met, I originally wrote a letter in support of naming this peak for him. I have subsequently changed my mind, and although I will not withdraw my letter of support, I no longer support this proposal. First of all, I now believe that Carl would not have wanted this kind of memorialization; he was too humble to want to call attention to himself. Secondly, I think naming peaks after people--whether in wilderness or not--draws attention from the feature and focuses it on the person commemorated.

If we want to commemorate Carl, establish a scholarship or endow a chair in environmental studies. This would be a lot more appropriate in my mind.

Rick Smith