Does the National Park Service need to log Yosemite to protect it from wildfire?/Rhea Cone file

New York Times Promotes Logging In Yosemite National Park

By George Wuerthner

The New York Times recently published an article titled At Yosemite, A Preservation Plan That Calls For Chainsaws. The idea that we need to log the forest to create healthy forests in a national park is a major threat to the management policies of the National Park Service, which generally promotes natural ecological and evolutionary processes.

The article states without qualification, “many experts say there is a consensus among scientists and political leaders on the need to thin and burn forests more proactively.”

The article suggests that humans always managed the landscapes in Yosemite and elsewhere. And that there is consensus that Indian burning kept the forests open. This view has been challenged but is not acknowledged in the New York Times piece.

Never mind that several scientific studies in Yosemite concluded that pre-European burning was primarily localized and had little influence on the forests.

For instance, a 2019 study in Yosemite concluded what is now Yosemite National Park, where historically, large Indigenous communities resided, was primarily influenced by climate, not human ignitions.

The study authors conclude: “We analyzed charcoal preserved in lake sediments from Yosemite National Park and spanning the last 1,400 years to reconstruct local and regional area burned. Warm and dry climates promoted burning at both local and regional scales…

The regional area burned peaked during the Medieval Climate Anomaly and declined during the last millennium, as the climate became cooler and wetter and Native American burning declined.

Our record indicates that (1) climate changes influenced burning at all spatial scales, (2) Native American influences appear to have been limited to local scales, but (3) high Miwok populations resulted in fire even during periods of climate conditions unfavorable to fires. However, at the regional scale (< 150 km from the lake), fire was generally controlled by the top-down influence of climate.”

Numerous studies have looked at Indian burning and its influence on fire regimes. Most work done by fire ecologists focusing on large landscape fires does not find any additive effect from Indigenous burning. Instead, climate/weather controls periods of significant wildfire activity (Baker W.L. 2002 Indians and fire in the U.S. Rocky Mountains: the wilderness hypothesis renewed. In Fire, Native Peoples, and the Natural Landscape, ed. T.R. Vale. pp. 41–76. Covelo, CA: Island Press. https://terkko.helsinki.fi/booknavigator/fire-native-peoples-and-the-nat...)

Unfortunately, this is an all-too-common premise of journalists who are not trained in ecology nor aware that there is an ongoing scientific debate about how essential fuels are in the creation of large fires and how effective thinning and burning fuel reductions may be.

These issues are central to the issue of national park management. Nothing is more at cross purposes with the values of national parks than manipulating the landscape to stop natural evolutionary processes. And indeed, that is precisely what logging Yosemite’s forests will do.

The idea that forests had to be less dense historically is based on fire scars. In fire scar studies, scientists wander through the forest looking for previously burnt trees. Often, the tree will heal after being burned, and that burn is recorded in tree rings as a scar. Scientists believe they can calculate past fire history by counting the fire-free intervals between scars.

Logging in Yosemite National Park is justified by flawed assumptions of historic forest conditions/George Wuerthner

However, there are many methodological problems with fire scar accuracy, which tend to shorten the interval between fires. In reality, the natural fire intervals in many areas may be far longer than commonly assumed, and thus the assumption that frequent fires kept forests less dense and more open could be inaccurate.

The article repeats the idea that fire suppression has created “unnaturally” dense forests. This premise is challenged by some researchers who suggest that Sierra Forests were always a mosaic of dense and open forests. However, this is not mentioned at all.

In an attempt to panic readers, the article notes that “more than 140 million trees killed” in California Sierra Nevada by drought and plagues of beetles over the past decade — 2.4 million of them in Yosemite alone. The article suggests that “forestry experts describe the state’s forests as wounded and extremely vulnerable.”

So let me get this straight. The Sierra Nevada forests, according to the advocates of logging/thinning, are too dense. Still, they lament that natural evolutionary selection by drought and insects, which has thinned the forest, has “wounded” the forest ecosystem.

A further problem with thinning to “restore” forests is that a logger cutting trees indiscriminately with a chain saw may be removing the trees most resilient to drought, insects, and other sources of mortality.

There are genetic differences among trees not visible by walking through a forest. For instance, some trees can expel bark beetles, and others are better able to cope with drought. Allowing natural processes to determine which trees are “winners” or “losers” is how you build resiliency into the forest ecosystem. Logging degrades the forest and may make the forest more vulnerable to future drought and insects.

Even the number of 140 million trees dead, which sounds like a huge number, lacks context. The Sierra Nevada forests cover 30 million or more acres. A typical lightly stocked forest stand will have 60-100 mature trees. So divide 140 million into 30 million means maybe 4-5 trees an acre, on average, have died, leaving behind dozens of other trees.

Of course, those alarmists who advocate for intervention will say the mortality is not evenly distributed, but that is irrelevant.

What we are seeing is the vegetation adapting to the new climate regime.

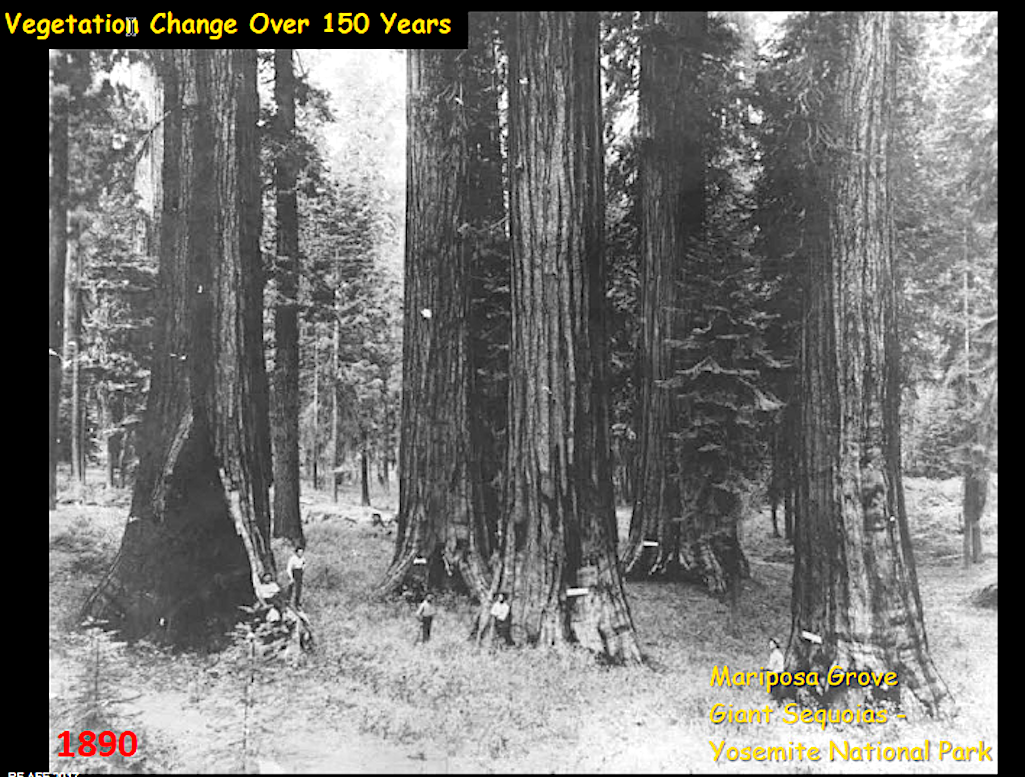

Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park 1890. Note the wide spacing of Sequoias, the absence of other conifers, and how a person could easily ride a horse or walk through this grove, as remarked on by many early explorers. These conditions were attributed to wildfires that burned on the landcape.

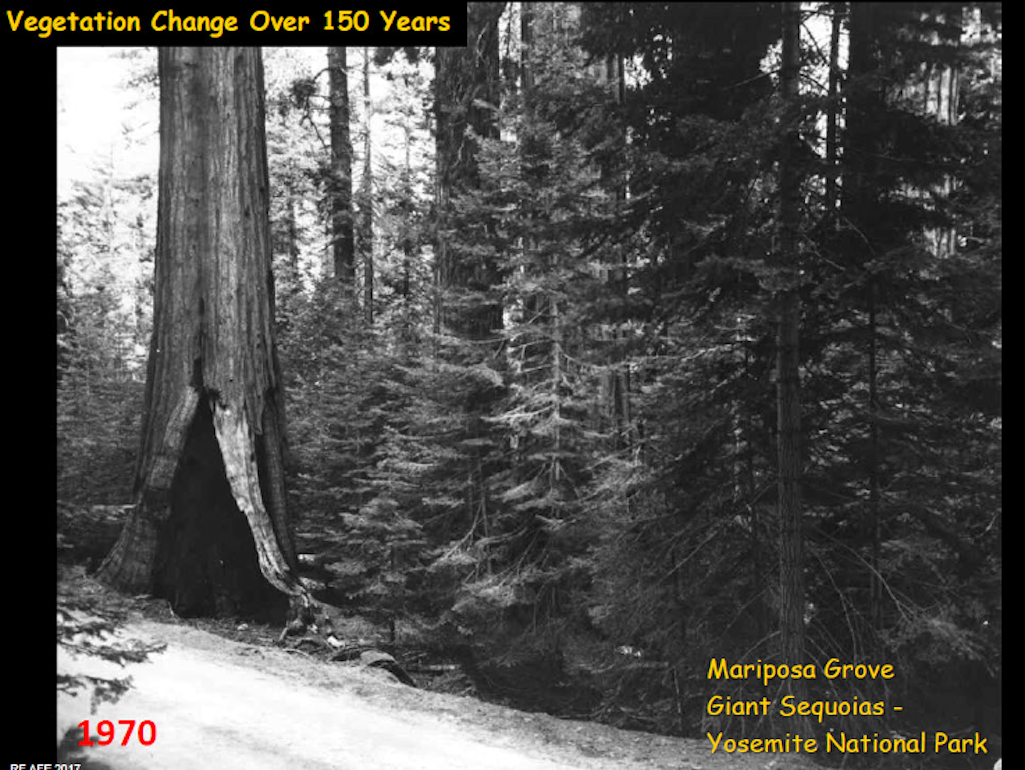

Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park, exact same scene as the shot above. In 80 years without fire, the rise of dense conifers was significant. In the late 1960s, the Park Service realized the benefits fire brought to Yosmite's forests and began prescribed burns to mimic natural wildfires.

Garrett Dickman, a forest ecologist at the park, is leading an effort to “restore” the area to what it looked like more than a century ago when he asserts native burning practices sculpted it. However, this ignores that the climate that created the “historic” Yosemite Forests no longer exists. The forests people see in Yosemite were primarily established during the Little Ice Age, when the climate was moister and cooler.

Today’s climate resembles the Medieval Warm Spell of 800-1300 AD. During this hot, dry period, there were massive forest fires all along the western slope of the Sierra Nevada. The study author Thomas Swetnam concluded: “This is one line of evidence that it was very fiery on the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada, and there’s a very strong relationship between drought and fire.”

It is also worth mentioning that the Sierra Nevada forests evolved over millions of years without any human influence, so the assumption that they require human manipulation to be “healthy” is another example of human hubris.

The giant sequoia groves now gracing the western slope of the Sierra Nevada likely got their start after high severity blazes that occurred during the Medieval Warm Spell. Sequoia cones open during heat, and most regeneration of the trees appears in the aftermath of a high severity fire.

Low severity fire does not sufficiently support sequoia regeneration, which is more evidence that Indian burning, typically characterized as “low severity,” could not have created the historic sequoia forest stands in Yosemite. Rather periodic high severity burns, promoted by severe drought, are the primary ecological agent for sequoia regeneration.

The New York Times article does give a small amount of column space to Dr. Chad Hanson, who opposes the Yosemite logging proposals. His and other scientists' research find that a heavily thinned forest is more vulnerable to fire, not less, because the cooling shade of the canopy is reduced, as is its effect as a windbreak. Many studies show that under extreme fire, weather, temperature, and wind are significant drivers of wildfire. Thinning increases the influence of temperature and wind on vegetation and wildfire spread.

We are in the worst drought in over a thousand years. We are seeing record high temperatures. Average wind speeds are increasing. These factors are responsible for the increase in wildfire spread and severity. For instance, for every 1-degree rise in temperature, fire risk is increased by up to 25 percent. Wind impact is also exponential, with high winds responsible for every large fire across the West.

The New York Times did a disservice to the understanding of wildfire influences and is helping to promote the unnatural modification of Yosemite’s forests. Promoting logging/thinning in national parks under the presumed assumption that one is “saving” them is yet another example of human hubris and will result in the domestication of our wildlands.

Traveler postscript: For additional insights into fire in Yosemite, check out this story about how the Washburn fire that recently burned near the Mariposa Grove is expected to stimulate a boom in sequoia trees. Another stories on sequoia trees and fire can be found here.

Comments

What a splendid, informative piece. I have spent decades in the fire literature of Yosemite and really seen few articles like it. Certainly, the debate has been ongoing for 150 years--all the way back to military management. As for management today, it is sadly deficient in historical understanding, and therein lies the problem for so many parks. Wilderness is an evolutionary construct and needs to be treated as such. If we ignore the evolution, i.e., the full and complete history, serious mistakes are bound to occur.

Well said. I could not agree more.

Its not vegetation change.. those photo's show the effects that commericial sheep herds had on the land.

Perhaps we should just bring back the sheep herds as it would be cheaper, more environmentally friendly, and less corrupt than the for profit logging plan...