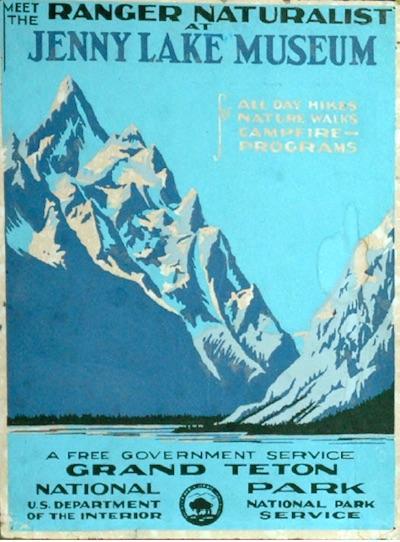

A chance discovery of an old poster at Grand Teton National Park led Doug Leen on a course of preserving the story of Works Progress Administration park posters/Rebecca Latson file

One Man's Crusade To Save National Park History

By Kurt Repanshek

Doug Leen is nothing if not persistent.

In the more than 150 years of national park history in the United States, a short four-year chapter hardly seems significant, and it surely would have vanished into obscurity were it not for Leen's determination not to let it fade away.

Those four years — from 1938 until 1941 — saw the Works Progress Administration embark on a colorful promotion of national parks with a collection of posters that enticed the public to visit these beautiful places.

The WPA was created to put the unemployed to work during the Great Depression. It was more than a producer of posters, funding construction of buildings and bridges, and employing musicians, writers, and actors. The program built parks, ski lodges, golf courses, skating rinks, and even ski jumps.

This is the original poster that Doug Leen found in a barn in Grand Teton National Park/Courtesy of Doug Leen

The national park posters truly were works of art. Some were based on postcard art, such as those images of Yellowstone National Park taken by F.J. Haynes beginning in the late 19th century, while the Zion National Park poster possibly came from a photo taken by the National Park Service's first official photographer, George Alexander Grant.

Studiously colored in buffs, umbers, blues, tans, oranges and reds, the posters captured park landscapes, depicted the wonders of the young park system, and invited the public to learn about these places. But only 14 park posters were produced in print before the onset of World War II shuttered the project.

Those 14 posters were designed for Grand Teton National Park (1938), Grand Canyon National Park (1938), Wind Cave National Park (1938), Glacier National Park (1939), Zion National Park (1939), Yosemite National Park (1939), Fort Marion National Monument (today's Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, 1939), Lassen Volcanic National Park (1939), Yellowstone National Park (1939, 2 posters), Mount Rainier National Park (1940), Great Smoky Mountains National Park (1940), Petrified Forest National Monument (1940, today a "national park"), and Bandelier National Monument (1941).

Leen tells their story, and part of his, in Ranger Of The Lost Art, Rediscovering The WPA Poster Art Of Our National Parks, a new coffee-table book.

"The incandescent magic of the national park posters included in Ranger of the Lost Art is enduring," presidential historian Douglas Brinkley who also has kept tabs on the history of the National Park System, writes in a foreword to the book. "Ranger Doug, gifted with a sharp curator's eye, works to promote the beauty and preservation of America's natural heirlooms."

The story that unravels in the book tracks not only the work of the WPA artists and graphic designers and how they approached it, but the approach Leen and his team took in faithfully reproducing not only the original 14 posters, but continuing on across the park system. Today he has completed about 60 park posters, both reproductions of the original 14 along with new editions his team created of other parks. His most recent poster promotes Harpers Ferry National Historical Park.

What this book does not delve deeply into is the dogged journey Leen took to track down copies of the original posters, some misappropriated, and his efforts to point out cheap copycats. You can learn more about those aspects of the WPA poster story in Traveler podcasts Episode 62 and 63. The short story is that Leen stumbled across one of the original Grand Teton National Park posters during his days as a seasonal ranger there in the 1970s, a discovery that later led him to search for the original 14 posters.

This book focuses on the too-short park poster work of the WPA and the passion the artists and designers put into it.

"They began in 1938, and by 1941 World War II came up and the whole project came to a screeching halt," Leen told the Traveler's Lynn Riddick for a recent podcast. "However, in 1938 the funding to the WPA and the Federal Art Project ... this all began to collapse. FDR was at the low point of his career at the time as president, and just like today, Congress began cutting drastically the funding for this museum project that made not only posters but made these dioramas and maps. Only 14 parks got these prints, and after the war they were completely forgotten about. They were tossed in the dustbin of history, as they say. And it wasn't until 1971 that I found what turned out to be the first poster that you might say resurfaced. It took me another 20 years, until 1992 or '93, that I realized that this is part of a federal series, it was made by the WPA, and actually come up with photographs of the original 14."

History doesn't always fade away, at least not in trends. The bold, colorful posters created by the WPA project nearly 90 years ago are back in vogue. More than a few companies have produced replicas, though Leen has been the most faithful in capturing the originals, both in his replicas and in the continuing series that his company has printed. But it's been more than a commercial endeavor for the man who spent seven summers at Grand Teton National Park as a seasonal ranger. He's been on a mission not just to preserve the history of the WPA poster project, but to see originals of the 14 posters made by the artists given to the federal government for posterity.

"Everything that I've possessed or been fortunate enough to find or to purchase is now back in the public domain," Leen told Riddick.

When Leen started reproducing the WPA posters, all he had to work from were black-and-white file photo negatives. For colors, he studied park brochures and documents and came up with a best guess for colorations.

"When I published my own version of these things, then originals began to show up," he recalled. "People would call me, they would say, 'I've got a poster, but it's a different color, what's going on, how come there are two different colored posters?' Then I knew they had an original."

Ranger Of The Lost Art goes into detail in describing the WPA work that went into creating each park's design. For the 14 originals, the book notes the year each was created, how the landscape designs came about, how many silk screens were created to apply the colors, and the number of original posters known to exist today. Surprisingly, parks did not always treat these posters as heirlooms.

"[Bandelier] had about twelve posters in the superintendent's office," Leen recounts in his book. "However, many of them had been cut in half to fit file drawers as dividers."

The book is a great placeholder of a period in national park history.

"The ability of art to inspire is ageless. And so it remains with our national parks," historian Alfred Runte wrote in a cover jacket blurb. "Their boundaries alone were never enough. Nor will today's promises any better protect the parks without rejecting narcissism for unity. Art, Doug Leen reminds us, empowers unity, both of purpose and desire. This is no time, whatever the country's failings, to let America the Beautiful die."

Added former NPS Director Jonathan Jarvis in another blurb, "Art and our national parks have a long history, starting when the landscape paintings by Alfred Bierstadt and Thomas Moran were used to inspire a movement for their preservation. That relationship grew exponentially when the Works Progress Administration hired artists to illustrate the national parks in a series of popular posters. Unlike Moran's famous Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, which hangs in the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, the WPA posters were nearly lost until Doug Leen recognized their significance and saved them from disappearance and destructiom. His new book brings them back to life, and through them, we can rekindle our relationship with our national parks."

Leen said he's devoted about 30 years or more of research to searching for the WPA originals, while the book concept started three years ago during the peak of the Covid pandemic.

"It was a long road to get this book," he recalled on Traveler's podcast. "It's everything I imagined, how this book turned out. ... I think it's a good story. It's kept me alive for 30 years."

Add comment