What is it like to work or live in a national park?

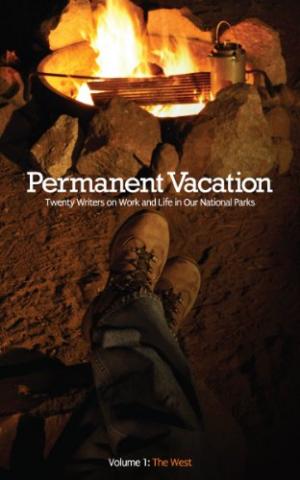

Permanent Vacations, published by Bona Fide Books, is a collection of 20 essays by writers who've experienced the Western national parks from the inside. The stories are not all about beautiful scenery or amazing animals but they all read authentic.

There are many ways to read a collection of essays. I started in the middle, reading about Denali National Park, the most recent vacation park I've been to.

I loved Christine Byl's description of Healy, Alaska, a gateway town to the park, the quintessential small-town one - two gas stations, a ratty bar, a truck-stop dinner with the usual gut-bomb breakfasts served all day.

Ms. Byl came to work as a seasonal on a trail crew, came to understand Denali, but eventually left the National Park Service. Still, she stayed in Healy and now runs a construction company with her husband. If you stay in Healy in the winter, you become a local. Her essay goes through the four seasons but winter takes up half the year. Tom Walker, in his essay about living just outside of Denali, describes the challenge of taking a short walk when it's -42 degrees outside.

Cassandra Kircher was ten when her father took the children camping in Grand Teton National Park. Seven years later, they head to Glacier National Park. The children hiked while the father fish.

But in the third part of the story, A Portrait of my Father in Three Places, Ms. Kircher is the one in charge. She's been a ranger for six years in Rocky Mountain National Park when her father visits her. He stays in her backcountry cabin but he's getting older and feebler. He manages to catch two trout but he can't kill them. That evening they have spaghetti for dinner. Ms. Kircher writes that, in spite of his fishing luck, my father has little energy.

The author struggles with her thoughts. I don't know what it feels like to be older and feebler than you'd like to be, but can't seem to talk to her father about it.

Mary Emerick, working in various parks, writes about The Men I Left Behind.

"The men I left behind were locals, tied by birth or desire to the small towns that fringed the national parks," she writes.

She explains that "... the real reason I left was because I had to go and they wanted to stay." But now, though, she writes, "I have lived on an island in Alaska for almost seven years now."

It seemed like the right choice for her because she didn't want to leave anyone behind anymore. She fell in love and got married. She traded her outdoor national park life for a deskbound job at the U.S. Forest Service in Oregon.

Keith Ekiss was an artist in residence in Petrified Forest National Park. He understands that writers need solitude, but "I'll admit that it's lonely at night." He's only at the park for two weeks and doesn't want to intrude into the personal lives of park personnel. But during the day, he has the privilege of driving out to a mesa to look at petroglyphs, away from the visitor spots. "I'm not in the middle of nowhere. People lived here," he has come to realize.

But the stories are not all by rangers and writers. Most Western parks have lodges run by concessioners and need all types of service personnel.

Nathan Rice rolls off his bunk at 5:45 a.m. to flip pancakes, fry hash browns, and scramble eggs for guests at Mount Rainier National Park's Paradise Lodge. He's here to explore the park and won't wait for his day off. One evening, Mr. Rice and his buddy, who works the dinner shift, start climbing Mt. Rainier at 9 p.m. They make it to the true summit at 14,410 feet in time to watch the sun rise. It's a difficult climb when you're fresh and rested, but to do this climb after a long day of work is amazing.

Melanie Dylan Fox, now living in southwestern Virginia, worked in the lodge at Sequoia National Park. She writes that "during almost every one of my five seasons in Sequoia National Park, an employee has been seriously injured in an alcohol-related accident. These incidents we keep to ourselves, like shameful secrets."

She had to learn the transient nature of the job and the people she worked with. "My first season, I exchanged addresses with everyone, not realizing the artificiality of this gesture; most people I would never see or hear from again."

Most writers were not full-time career park personnel, but Robert Cornelius is an exception. He writes a simple story entitled A Chance Encounter in Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park in Colorado. Mr. Cornelius was three months from retiring from the National Park Service when he met a father and son on the trail. After answering the ten-year-old boy's many questions, the ranger saw a bighorn sheep. He called the visitors back and pointed out the sheep that was almost camouflaged.

"I'll never forget this for the rest of my life!" the boy said.

On that day, Mr. Cornelius felt he had passed the torch to the next generation of national park stewards. I must admit that it brought tears to my eyes.

Kim Wyatt, publisher of Bona Fide Books, explains that the essays were arranged in an arc, from an essay by the most transient employee to the most permanent. This is the first book published by this small press in the Lake Tahoe Basin, though there are several in the pipeline.

Ms. Wyatt says that her mission is "to promote new writers. I know so many good writers that are being rejected. The 20 writers are good at what they do. I'm not specializing right now. I don't intend to be a regional writer."

Ms. Wyatt's life is reflected in several essays.

"I moved to Yosemite when I was 18 years. Most of the time, I worked at the high camps in Tuolumne Meadows. In the winter, I worked down in the Yosemite Valley. Then I moved to Alaska where I trained as a nurse," she explains. "I started writing and ultimately received an MFA in non-fiction. I'm interested in nature and the interaction between nature and people. I love it that visitors spend their precious free time in the national parks."

A call for stories from Eastern Parks

Bona Fide Books now seeks stories about national parks from east of the Mississippi. Whether you spent your time hitting the trails or alligator-proofing your cabin, they would love to read your experiences. We welcome tree-hugging epiphanies and reflections on the daily grind. From the Everglades to Acadia, what are the societal, environmental, and existential implications of living in the park. What happened there? How did you get hooked? What keeps you coming back? The stories need to be about the National Parks and not about other NPS units.

Essays should be approximately 5,000 words or less. Writers will receive $100 for their essay and one copy of the collection. They are accepting submissions through January 1, 2012. For all details see their website.

You can buy Permanent Vacation on the Bona Fide website, in several Western parks, and in gateway communities and of course, on Amazon.

Comments

Like Nathan I, too, worked summers at Paradise Inn in Mount Rainier National Park. We were not allowed to have cars due to lack of parking space, so we stayed up there from early June through mid-September. I lived for my one day off per week so I could hike the trails, photograph wildflowers, breathe in the sweet air. I have so many memories of those summers, and I am happy to say I still keep in touch with friends I made there nearly 35 years ago.

9-17-11

I saw the call for experiences of people who have worked in Eastern national parks via the Association of National Park Rangers Facebook page, and I was prepared to write something, because I spent 7 years working as a seasonal ranger in several western and eastern NPS units. And the key word of the last sentence is "units". Why only a focus on national parks? Some of the best and most interesting protected areas under NPS management are not national parks. In the east I was a patrol ranger at Cape Cod National Seashore, and I also worked at one of the most unique areas of all, Statue of Liberty National Monument. I could write a great article about how Statue of Libery has changed due to 9/11 between the summer I was there (1988) and the last time I visited (2004), but because it isn't a national park, I guess you aren't interested. A fascinating subset of rangers in the eastern U.S. are those working at military parks - known informally as "the cannonball parks", but they can't submit either. If this policy changes send me an email and I will draft something that I would hope you find worthy of consideration. Thanks.

Paul Bignardi

San Mateo, CA