Map discovered in the National Archives that points to a 1930s' plan to create an international park along the Texas-Mexico border near present-day Big Bend National Park/Jason Abrams

Editor's note: Two brothers, Jason and Zach Abrams, have stumbled upon a batch of letters dating to the 1930s and 1940s that they believe detail plans to create a large public works project in what is now Big Bend National Park. In the following article, the brothers provide a glimpse of what they've been able to piece together from those letters and additional research.

A man in Raleigh, North Carolina, “re-discovered” a cache of 34 letters in January 2014 while cleaning his garage after a water pipe began leaking. After nearly 30 years, the correspondences remained tucked inside manila archival folders labeled “miscellaneous stationary, 1934-41” and stored flat in a cardboard box with other paper collectibles, including a World War I naval aviator certificate.

Now he claims the letters provide connections between known but seemingly unrelated events in Texas history and ultimately reveal the largest unknown political conspiracy of the Great Depression.

Jason Abrams, 42, first discovered the letters in 1986 while digging through a bin of loose papers in a local tomato packing warehouse-turned antique store in Miami, Florida. He purchased the letters and other random items for $5, with no idea who received them or what they meant. The typewritten correspondences were addressed to an Albert W. Dorgan, of Castolon, Texas—now a ghost town preserved as a historic district in Big Bend National Park. What Abrams recalls most vividly is that the letters were all hand-signed and on official government stationary, with letterheads including “Department of State,” “Congress of the United States,” and “The White House.”

The letters document a discrete campaign by the Texas congressional delegation to fund a massive international public works project in what is now Big Bend National Park. In 1933, Texas began to pursue federal relief funds to construct the largest and most complex international public works project of the New Deal era—a recreation area on the Rio Grande complete with hydroelectric dams, artificial lakes, highways, tourist resorts, and self-sustaining model communities along the Lower Rio Grande. If successful, Texas would create thousands of jobs overnight and earn millions in perpetual revenue from tourism and sale of hydroelectric power to Mexico.

After 22 months of fulltime research, Abrams discovered that Texas pursued a clandestine campaign to establish a U.S.-Mexico "international park" in Big Bend. If Congress viewed the park as a matter of ongoing foreign relations, the State Department would finance all construction costs and assume responsibility for perpetual maintenance. However, the Department of the Interior wanted Big Bend as a national park and for nearly a decade state legislators fought a campaign to prevent--not assist--the National Park Service from establishing a park in Big Bend. This preserved development options for dams, highways, and an international park.

“Less than a third of Big Bend’s founding history is known to the public” said Abrams. “This is about to change.”

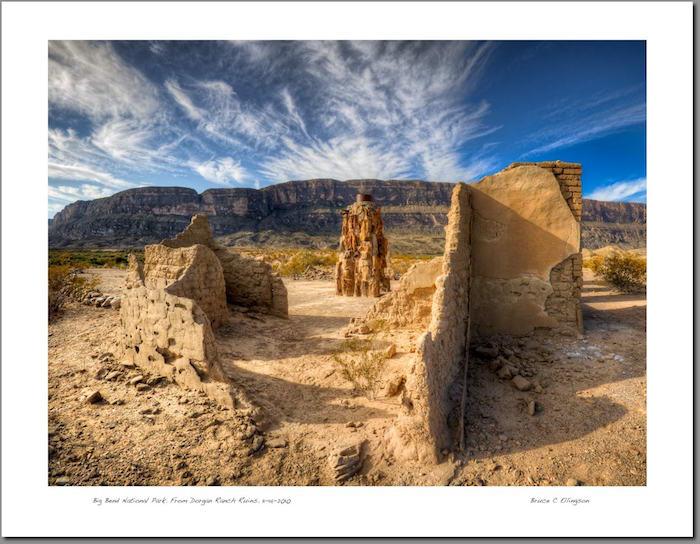

Was Albert Dorgan, whose ranch ruins can be found in Big Bend National Park, involved in a scheme to create an international park along the Texas-Mexico border in the 1930s?/Bruce Ellingson

Letters to Castolon: Cracking the Code

Fellow researcher Zach Abrams commented that, “we knew immediately that the letters were significant, but we needed to answer two basic questions: what exactly are these people writing about, and why are they writing to a farmer in a town like Castolon?”

In 1935, Castolon was an isolated border community along the Rio Grande in Big Bend, over 80 miles from the nearest town and with less than 25 residents. The ruins of Dorgan’s custom adobe home—complete with a two-way central fireplace made of petrified wood—are considered one of the most significant architectural features in Big Bend. Per current accounts, Dorgan lived in Big Bend during the 1930s, operated an irrigated floodplain farm with his neighbor, and left Big Bend in 1938 due to his wife’s declining health.

The content and sheer volume of correspondences in the cache suggested that farming was not Dorgan’s sole occupation in Castolon. Many letters include vague references to an “international” or “Pan American Peace Park” on the Rio Grande. No such park exists. Others simply acknowledge receipt of “maps and plans,” often returned to Dorgan “per request” and “under separate cover.”

Abrams searched for “A.W. Dorgan” and “Castolon, Texas” expecting a laundry list of results for a man inventing dirigibles and receiving mail from the highest offices of state and federal government. Dorgan was not only rarely mentioned in the literature, but conspicuously absent. Abrams contacted the National Park Service history program in Washington, which confirmed the material was “of significant value to future researchers.” Unfortunately, Park Service historians had no idea what the letters meant. Ditto for park staff in Big Bend. For Abrams, “this left me searching for a man that barely existed, and working on toward establishing a park that does not exist.”

A letter from The White House to Castolon defied any reasonable explanation. On March 11, 1935, presidential secretary Louis McHenry Howe confirmed receipt of Albert Dorgan’s “design of dirigible, and have placed it before the President.” Howe informed Dorgan that President Roosevelt “has asked me to thank you for your kindness in writing and to forward your communication to the Secretary of the Navy for consideration.” Why would a farmer design a dirigible for President Roosevelt? And why was Roosevelt not only thanking this alleged “farmer” in writing, but also forwarding his communication to the Secretary of the Navy?

More questions emerged. The cache contained a half dozen letters from the State Department, another half dozen from the House and Senate Committees on Military Affairs in Washington, and letters from the House and Senate in Austin. A 1937 letter from The Texas Planning Board invited Dorgan to give their director a hearing “at your convenience.” Of all the agencies represented in the letter cache, there were two notable absences: the National Park Service and the Texas State Parks Board. For a man receiving dozens of letters discussing park development in Big Bend, it seemed odd that he avoided the two agencies most closely associated with park development.

Six correspondences contained a State Department decimal file code for reference in further communications. Staff at the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland, advised that the letters were part of a larger file on “border questions” between the United States and Mexico. Abrams first visited the archives in July 2014 to search for the matching correspondences; he uncovered what he calls a “treasure trove” of lost American history—including two large color maps drafted by Dorgan in 1935 for President Roosevelt.

Traveler footnote: Authors Jason and Zach Abrams are preparing to share this unprecedented and untold story of New Deal brinksmanship and intrigue in a book titled “Forgotten Frontiers: Texas and the Battle for Big Bend National Park.” Abrams plans to create a gorgeous, professionally designed, full color hardcover coffee table book revealing this unknown chapter of the Great Depression not only in words, but through the eyes of those who witnessed this era firsthand. Readers will experience New Deal Texas through posters, brochures, newspaper clippings, cartoons, pamphlets, press material, steamer trunk labels, ticket stubs, commemorative artwork--and reprints of the entire cache of letters that revealed the largest unknown political conspiracy of the time.

“If New Deal Texas kept a scrapbook of hidden Big Bend history, this would be it,” said Abrams. For more on the largest unknown political conspiracy of the Great Depression that is rewriting the founding of Big Bend National Park, experience this history today at this website.

Comments

None of this is a secret, and no one with any knowledge of area history would call Dorgan a "farmer." He was a real estate developer who was well-known for multiple attempts to create a Disneyland-style theme park at Castolon-Santa Elena. Everything except perhaps the dirigible is already documented in various books currently available from UT Press, TAMU Press, and Texas Tech press.

Can you recommend any books by any of these presses that reference this material? Aside from the Jameson work, none of this is in print. All of this is known (lol). Thanks, Jason.

I would definitely be interested in learning more about the conspiracy part of the story. Does the National Park Service know about this find?

i can't wait to read the book!!!

We think you know more than you may admit about this so-called conspiracy, Mr. Maxwell.

I read the website. It reminds me a lot of the Elephant Butte irrigation district scandal in New Mexico. Fascinating stuff.

When volunteering with BIBE interpretation in the late '90s, I.wrote a program and gave local history tours of the area between Castolon and Terlingua Abaja, which included the Dorgan homestead ruins. The comments of AW are absolutely correct. There was no big secret -- Dorgan was a visionary and his proposals for a resort in the area are already well-documented in park archives, oral histories and published books. There are always differing views and objectives, which translate into political intrigue, and this occurred in the Big Bend same as elsewhere.

I have been to the Dorgan ruins in Castolon several times over the years. It has been awhile but I don't remember reading about this at the historic site. Seems like Dorgan was an active fellow. I believe the post office is still there.