Barbed wire at Manzanar National Historic Site/Lee Dalton

December 7, 1941. That day that lives in infamy. I was 11 months and five days old. I don’t remember that day, but do have a jumbled assortment of vague recollections of a time I thought I understood. My uncle in an air raid warden’s helmet. Sitting in the dark because my mother told me it was something called a blackout. Carrying buckets of bacon grease to a collection center to be used in making ammunition my father could fire from his tank in Italy. My uncle’s car sitting on a jack with a flat tire while he and my aunt walked to work because new tires were needed somewhere else. And frightful posters bearing portraits of scary people my mother said were our enemies.

Or at Fort Knox when my mother sent me with lemonade for Italian prisoners of war who were mowing our lawn and the GIs who were guarding them. One of those scary men grabbed me and hugged me and said in a strange accent, “I’va got a leettle boy like you!” Mostly I remember his tears and how the soldier guarding him came running until he realized what was happening.

I thought I understood that time. I’d studied history, after all, in high school and in college. I’m an American and our history is known to all of us . . . isn’t it?

Then came this week. A week when I realized — again — how little I really understand and how much I’ve forgotten.

Driving south from Tahoe on Highway 395 listening to NPR and a program about how it was once members of the Democratic Party who tried with all their might to terrify and even kill those who believed Black people should vote. I heard voices reading words spoken and written by some brave people before they were beaten or lynched for daring to push for change. I had completely forgotten that Democrats were once the party of hate in our South. I’ve also almost forgotten how it was once Republicans who stood up for labor, for unions, and for common people. I dimly recalled how roles reversed when I and other Americans became distracted and stopped paying attention.

I pulled into a roadside rest and found a panel telling the story of how Paiutes from the Owens Valley had been marched 250 miles to displace them from lands then coveted by others. I’ve heard other stories like that. The Long Walk of the Navajo and Cherokee Trail of Tears. But those memories rest somewhere in shadow. Then I found another panel that told the story of Europeans who replaced the Paiutes and who were themselves forced from their homes when the City of Los Angeles took the valley’s water to quench its endless thirst.

I recall stories of my Irish ancestors and their tales of signs that said “No Irish Need Apply.” I used to hear all the Italian jokes. And now every night on TV news I hear more about the horrible Mexicans and fearsome Muslims who are invading our great nation.

Then I pulled into the parking lot at Manzanar. Some places capture your eyes with spectacular scenery. But Manzanar National Historic Site captures your heart.

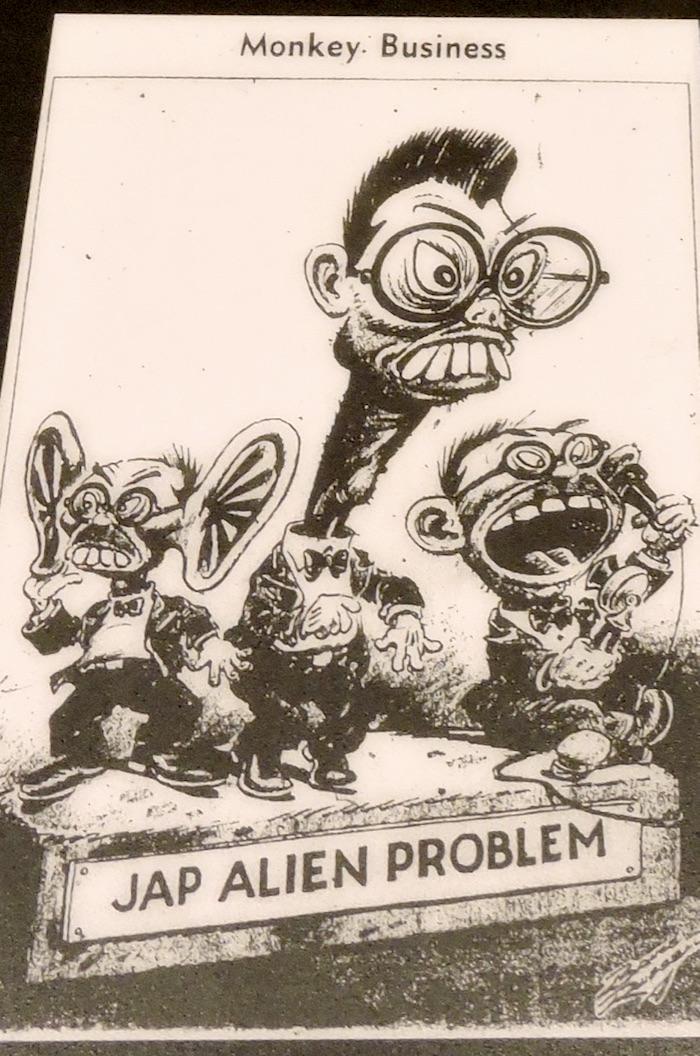

Fanning the hatred from another generation

At Manzanar, we walk through story after story of an American tragedy. We witness pictures and words of people who experienced a time when fear and hatred took possession of our nation in one of the dark chapters of our history. Manzanar is one of the places where thousands of people were sent for one reason only.

They were Japanese.

I’m sure you’ve all heard tales of what happened after December 7, 1941. How tens of thousands of Japanese merchants, teachers, fishermen, businessmen, clergy, children, and even Catholic nuns were rounded up and sent with only what they could carry to ten “internment camps” well away from the West Coast. One more shameful story not much different than others like the Trail of Tears, the Long Walk, and those Paiutes who had lived once in the very place to where these Japanese were hauled.

It’s a story that was long neglected. Some of us didn’t want to teach this to our kids in their history books. Maybe because some feared it might not grow proper pride and patriotism in their young minds. Besides, these people — these Japs — were different. Always had been. Always would be.

Once upon a time our own Supreme Court had ruled that Japanese who came to America could not become citizens. Although our Constitution assured that their children who were born here were citizens. There were efforts made in high places to find a way to stop that, too. It was even against the law for a Japanese — or Chinese, or Black person for that matter — to marry a Caucasian American.

But now those stories — and others like them from our history — are finally being told. Even right now at a time when measures were recently introduced into Congress that could deprive some other Americans of their place and citizenship here and send them off to the south.

Exhibits in Manzanar’s visitor center and throughout the rest of the site are some of the best I’ve seen our parks. There’s nothing really fancy. Very little electronic gadgetry. But lots of pictures. And, I think, most effective of all, the words of people who actually lived the story told here.

This wasn’t long ago. Although they are rapidly leaving us now, these people were able to tell their stories firsthand. We see their faces and hear their voices. Some of the most moving and effective are a series of simple watercolor portraits of people with names like Yoshinaga or Hayashida. Below each portrait are just a few words that, if you take time to think while reading them, hit you like a jolt right in the gut and in your heart. Or at least they should.

Waiting to be sent to detention camp

I even learned in the bookstore that our beloved Dr. Seuss had been a political cartoonist before the war and his cartoons had fanned flames of hate and distrust.

There’s no way to do justice to the story of Manzanar. It’s something you have to experience and if it doesn’t touch your heart and leave you angry or perhaps even tearful then there has to be something wrong with you . . . . .

Manzanar Superintendent Bernadette Johnson talked with me for a long time after I met her at the information desk. She’s a tiny woman. Obviously Hispanic with a Scandinavian name. It took about 30 seconds for me to realize that I’d just met one of those remarkable folks I wish everyone could meet and learn from. She shared some personal stories that explain why the story told here is so precious to her. Stories of her own adoption that had me fighting down tears right there in front of the visitor center desk.

One of her ambitions for Manzanar is to find a way to set up some kind of interpretive wayside or something that will tell the story of the Children’s Village here. She says this is one of the most tragic tragedies of the internment. Orphans who had been living in orphanages in West Coast communities who happened to be Japanese were also rounded up and shipped here. Some, who had been in foster care or were in the process of being adopted were taken from their homes and sent to the Children’s Village at Manzanar. They were orphaned twice!

We talked of how the staff here are all dedicated to trying to tell a story that portrays a time in our history that was not our best. She says it’s rewarding to watch as visitors actually have their minds and ideas changed by what they learn here.

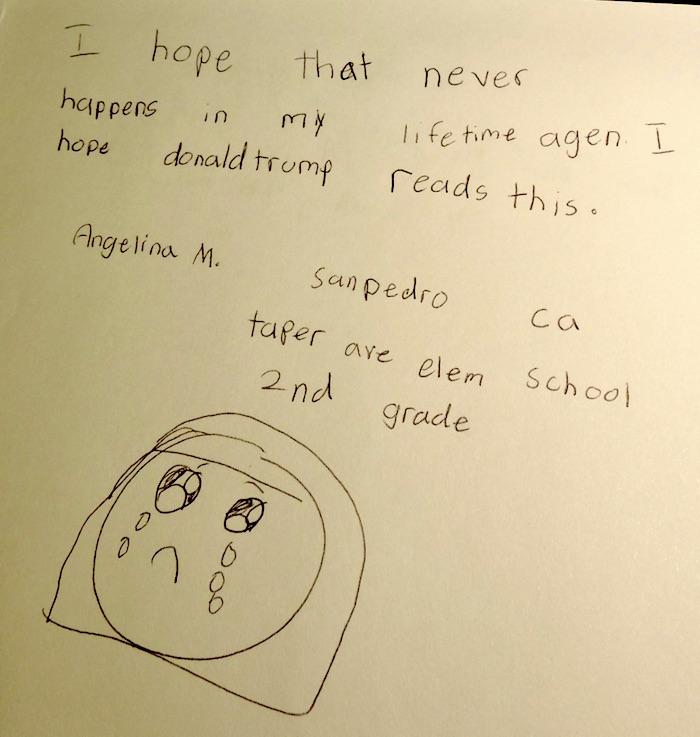

She told of an entry in the large comment book that’s set out for visitors. It said, “I am 77 years old. I’ve always hated the Japanese but what I learned here taught me how wrong I was. I’m sorry. Please forgive me.”

I asked if the current political climate and racial divisiveness that seems to be growing and gripping us again today causes problems for interpreters here. “No,” she replied. “We just tell the story of what happened and let people make up their own minds.”

She reminded me that Manzanar actually tells three stories of personal tragedies for Americans. The first came in the late 1800s as European settlers began displacing Paiutes. Original Americans. As had happened before in other places, there finally came the Long Walk of the Paiutes when they were forced to march some 250 miles away. Several of them died along the way. Descendants of some of them are the Button family who live nearby and whose civic efforts now help support the park.

Privacy was not a consideration at Manzanar/Lee Dalton

There had once been a thriving town around apple orchards named Manzanar. The people who settled here and planted the trees were driven away by wind. Wind that stripped blossoms and young fruit from trees. Manzanar was abandoned and the land was sold to Los Angeles. While in other parts of the Owens Valley, European settlers were often forced from their homes as the growing city gobbled up water rights to slake its thirst. Without water, there wasn’t much left for anyone here.

And finally, when the government needed an empty place to build a camp for Americans whose eyes were different than the rest of us, the square mile that had been Manzanar was the spot. Then, after a pause the Hispanic superintendent quietly asked, “So who could be next? It could be me . . . or even you.”

When Japanese young men were finally allowed to join the U.S. Army, thousands volunteered from Manzanar and Topaz, from Minidoka and all the others. They became the 442nd Infantry. The Purple Heart Brigade. The most decorated outfit in the Army. Sadao Munimori from Manzanar was awarded the Medal of Honor after he threw himself on a German grenade to save his buddies in Italy.

One of the most moving exhibits is that collection of watercolor portraits of people who were interned here. One stood out to me. Jack Kunitami wearing an American Legion cap and his words: “I did my share. I had complete faith in America.”

As they were loaded into trucks for transport, internees could take only what they could carry. A mother named Fumiko Hamashida wrote: “My suitcase was full of diapers and children’s clothes.”

In one of the barracks, visitors may push buttons and listen to voices of real people who once lived and experienced Manzanar. I watched a woman listening and wiping tears from her eyes. When I listened, I had to wipe my eyes, too. I spent a long time turning pages in that big book where visitors are invited to write and gave thanks that I saw note after note from other Americans — apparently of all colors and heritages — who were disgusted and ashamed after they had wandered and read the words and looked at those countless photos on panel after panel of displays. It’s good to know there’s a sense of alarm out there now — at a time when some people in power are trying to fan and use fear of other people to support whatever their goals may be.

This is a place that obviously touches the hearts and minds and consciences of many thoughtful people. It’s a powerful antidote for ignorance that fuels the stupidity of fear and hate.

And that, to my simple mind, is a wonderful thing to behold.

As long as the world lasts there will be wrongs, and if no man rejected and no man rebelled, those wrongs would last forever. — Clarence Darrow

Comments

If their "mistakes" (a anachronism in itself) is relevant to the current situation. It isn't. The two couldn't be more different.

Whew! Whiplash! Right into opinion without even stopping to coordinate pronouns, and not a single "in my opinion", "the way I see it", or even the slightly stilted "if you will...".

Try that for a while - whenever you depart from clearly documented data, put a "in my opinion" into every sentence. It's a damn nuisance, but so are most needed disciplines.

I'm afraid that a comment like yours, above, would have been laughed out of every college course I took, except for the electives of fencin & ballet. Proclaiming something to be true ex cathedra like that has absolutely no credibility.

Sorry Rick, I thought the differences were self evident. It appears they are beyond your comprehension. We were visiously attacked by the country of Japan. We haven't been bombed by Mexico. We declared war on Japan, we haven't declared war on Mexico. The US Government was fearful that Japanese citizens would perform subversive acts to aid Japan's war, there is no such fear with our current illegals. The interred Japanese were US Citizens legally inside the boarders of the US. The interred illegals, are illegal, having entered the country against the law. All documented data and two very different scenerios.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/26/us/korematsu-supreme-court-ruling.html

Korematsu, Notorious Supreme Court Ruling on Japanese Internment, Is Finally Tossed Out...(Internment Based on Lie)

A Japanese internment camp in Manzanar, Calif., in 1942. In upholding President Trump's travel ban on Tuesday, the Supreme Court also overruled the case that had allowed the World War II internments as constitutional.CreditBettmann Archive

By Charlie Savage

June 26, 2018

"But on Tuesday, when the Supreme Court's conservative majority upheld President Trump's ban on travel into the United States by citizens of several predominantly Muslim countries, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. also seized the moment to finally overrule Korematsu."

"The forcible relocation of U.S. citizens to concentration camps, solely and explicitly on the basis of race, is objectively unlawful and outside the scope of presidential authority," he wrote. Citing language used by then-Justice Robert H. Jackson in a dissent to the 1944 ruling, Chief Justice Roberts added, "Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and -- to be clear -- 'has no place in law under the Constitution.'"

"In a dissent of the travel ban ruling, Justice Sonia Sotomayor offered tepid applause. While the "formal repudiation of a shameful precedent is laudable and long overdue," she said, it failed to make the court's decision to uphold the travel ban acceptable or right. She accused the Justice Department and the court's majority of adopting troubling parallels between the two cases."

m13 - I agree, if the government had stuck to the Constitution, Manzanar whould not have happened. That is the danger of a "living Constitution".

I also agree with the self-evident truths that Justice Sotomayer mentions.

Lee, this is a wonderful, moving, and important essay on Manzanar. As a professional historian, though, I need to respond to Rob Richmond's comment that "Anyone who says the Japanese were interned for racial reasons has not done their homework," which is simply wrong. Actually, the notion that "the Japanese were interned for racial reasons" was the judgment of the Reagan administration in 1982 in the report issued by the federal government titled "Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians." The commission did extensive "homework" and concluded that the measures taken against Japanese Americans in WWII "were motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." The report is available from the National Archives at https://www.archives.gov/research/japanese-americans/justice-denied . The federal government subsequently acknowledged the injustice of the internment camps when Congress passed and President Reagan signed the 1988 Civil Liberties Act that apologized for the internments and paid compensation to the victims.

Also, Rob, I find it a matter of concern when I read someone's long polemic which [a] minimizes a focus on past racial injustice as a negative bias, [b] and also expresses the dangerous opinion that "few understand" things as you do.