Barbed wire at Manzanar National Historic Site/Lee Dalton

December 7, 1941. That day that lives in infamy. I was 11 months and five days old. I don’t remember that day, but do have a jumbled assortment of vague recollections of a time I thought I understood. My uncle in an air raid warden’s helmet. Sitting in the dark because my mother told me it was something called a blackout. Carrying buckets of bacon grease to a collection center to be used in making ammunition my father could fire from his tank in Italy. My uncle’s car sitting on a jack with a flat tire while he and my aunt walked to work because new tires were needed somewhere else. And frightful posters bearing portraits of scary people my mother said were our enemies.

Or at Fort Knox when my mother sent me with lemonade for Italian prisoners of war who were mowing our lawn and the GIs who were guarding them. One of those scary men grabbed me and hugged me and said in a strange accent, “I’va got a leettle boy like you!” Mostly I remember his tears and how the soldier guarding him came running until he realized what was happening.

I thought I understood that time. I’d studied history, after all, in high school and in college. I’m an American and our history is known to all of us . . . isn’t it?

Then came this week. A week when I realized — again — how little I really understand and how much I’ve forgotten.

Driving south from Tahoe on Highway 395 listening to NPR and a program about how it was once members of the Democratic Party who tried with all their might to terrify and even kill those who believed Black people should vote. I heard voices reading words spoken and written by some brave people before they were beaten or lynched for daring to push for change. I had completely forgotten that Democrats were once the party of hate in our South. I’ve also almost forgotten how it was once Republicans who stood up for labor, for unions, and for common people. I dimly recalled how roles reversed when I and other Americans became distracted and stopped paying attention.

I pulled into a roadside rest and found a panel telling the story of how Paiutes from the Owens Valley had been marched 250 miles to displace them from lands then coveted by others. I’ve heard other stories like that. The Long Walk of the Navajo and Cherokee Trail of Tears. But those memories rest somewhere in shadow. Then I found another panel that told the story of Europeans who replaced the Paiutes and who were themselves forced from their homes when the City of Los Angeles took the valley’s water to quench its endless thirst.

I recall stories of my Irish ancestors and their tales of signs that said “No Irish Need Apply.” I used to hear all the Italian jokes. And now every night on TV news I hear more about the horrible Mexicans and fearsome Muslims who are invading our great nation.

Then I pulled into the parking lot at Manzanar. Some places capture your eyes with spectacular scenery. But Manzanar National Historic Site captures your heart.

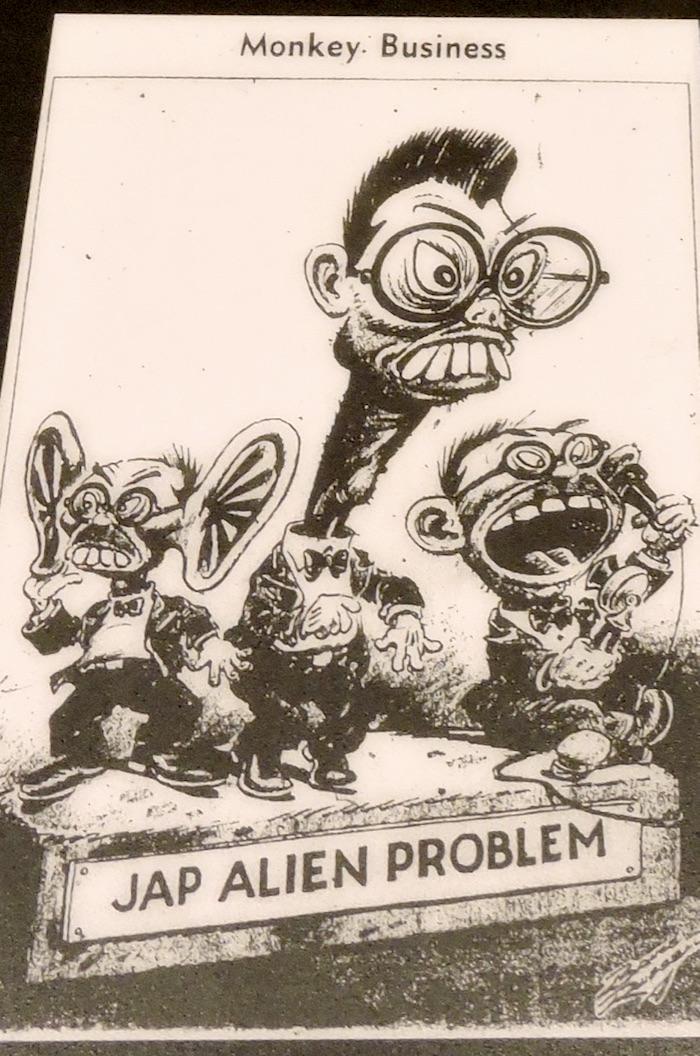

Fanning the hatred from another generation

At Manzanar, we walk through story after story of an American tragedy. We witness pictures and words of people who experienced a time when fear and hatred took possession of our nation in one of the dark chapters of our history. Manzanar is one of the places where thousands of people were sent for one reason only.

They were Japanese.

I’m sure you’ve all heard tales of what happened after December 7, 1941. How tens of thousands of Japanese merchants, teachers, fishermen, businessmen, clergy, children, and even Catholic nuns were rounded up and sent with only what they could carry to ten “internment camps” well away from the West Coast. One more shameful story not much different than others like the Trail of Tears, the Long Walk, and those Paiutes who had lived once in the very place to where these Japanese were hauled.

It’s a story that was long neglected. Some of us didn’t want to teach this to our kids in their history books. Maybe because some feared it might not grow proper pride and patriotism in their young minds. Besides, these people — these Japs — were different. Always had been. Always would be.

Once upon a time our own Supreme Court had ruled that Japanese who came to America could not become citizens. Although our Constitution assured that their children who were born here were citizens. There were efforts made in high places to find a way to stop that, too. It was even against the law for a Japanese — or Chinese, or Black person for that matter — to marry a Caucasian American.

But now those stories — and others like them from our history — are finally being told. Even right now at a time when measures were recently introduced into Congress that could deprive some other Americans of their place and citizenship here and send them off to the south.

Exhibits in Manzanar’s visitor center and throughout the rest of the site are some of the best I’ve seen our parks. There’s nothing really fancy. Very little electronic gadgetry. But lots of pictures. And, I think, most effective of all, the words of people who actually lived the story told here.

This wasn’t long ago. Although they are rapidly leaving us now, these people were able to tell their stories firsthand. We see their faces and hear their voices. Some of the most moving and effective are a series of simple watercolor portraits of people with names like Yoshinaga or Hayashida. Below each portrait are just a few words that, if you take time to think while reading them, hit you like a jolt right in the gut and in your heart. Or at least they should.

Waiting to be sent to detention camp

I even learned in the bookstore that our beloved Dr. Seuss had been a political cartoonist before the war and his cartoons had fanned flames of hate and distrust.

There’s no way to do justice to the story of Manzanar. It’s something you have to experience and if it doesn’t touch your heart and leave you angry or perhaps even tearful then there has to be something wrong with you . . . . .

Manzanar Superintendent Bernadette Johnson talked with me for a long time after I met her at the information desk. She’s a tiny woman. Obviously Hispanic with a Scandinavian name. It took about 30 seconds for me to realize that I’d just met one of those remarkable folks I wish everyone could meet and learn from. She shared some personal stories that explain why the story told here is so precious to her. Stories of her own adoption that had me fighting down tears right there in front of the visitor center desk.

One of her ambitions for Manzanar is to find a way to set up some kind of interpretive wayside or something that will tell the story of the Children’s Village here. She says this is one of the most tragic tragedies of the internment. Orphans who had been living in orphanages in West Coast communities who happened to be Japanese were also rounded up and shipped here. Some, who had been in foster care or were in the process of being adopted were taken from their homes and sent to the Children’s Village at Manzanar. They were orphaned twice!

We talked of how the staff here are all dedicated to trying to tell a story that portrays a time in our history that was not our best. She says it’s rewarding to watch as visitors actually have their minds and ideas changed by what they learn here.

She told of an entry in the large comment book that’s set out for visitors. It said, “I am 77 years old. I’ve always hated the Japanese but what I learned here taught me how wrong I was. I’m sorry. Please forgive me.”

I asked if the current political climate and racial divisiveness that seems to be growing and gripping us again today causes problems for interpreters here. “No,” she replied. “We just tell the story of what happened and let people make up their own minds.”

She reminded me that Manzanar actually tells three stories of personal tragedies for Americans. The first came in the late 1800s as European settlers began displacing Paiutes. Original Americans. As had happened before in other places, there finally came the Long Walk of the Paiutes when they were forced to march some 250 miles away. Several of them died along the way. Descendants of some of them are the Button family who live nearby and whose civic efforts now help support the park.

Privacy was not a consideration at Manzanar/Lee Dalton

There had once been a thriving town around apple orchards named Manzanar. The people who settled here and planted the trees were driven away by wind. Wind that stripped blossoms and young fruit from trees. Manzanar was abandoned and the land was sold to Los Angeles. While in other parts of the Owens Valley, European settlers were often forced from their homes as the growing city gobbled up water rights to slake its thirst. Without water, there wasn’t much left for anyone here.

And finally, when the government needed an empty place to build a camp for Americans whose eyes were different than the rest of us, the square mile that had been Manzanar was the spot. Then, after a pause the Hispanic superintendent quietly asked, “So who could be next? It could be me . . . or even you.”

When Japanese young men were finally allowed to join the U.S. Army, thousands volunteered from Manzanar and Topaz, from Minidoka and all the others. They became the 442nd Infantry. The Purple Heart Brigade. The most decorated outfit in the Army. Sadao Munimori from Manzanar was awarded the Medal of Honor after he threw himself on a German grenade to save his buddies in Italy.

One of the most moving exhibits is that collection of watercolor portraits of people who were interned here. One stood out to me. Jack Kunitami wearing an American Legion cap and his words: “I did my share. I had complete faith in America.”

As they were loaded into trucks for transport, internees could take only what they could carry. A mother named Fumiko Hamashida wrote: “My suitcase was full of diapers and children’s clothes.”

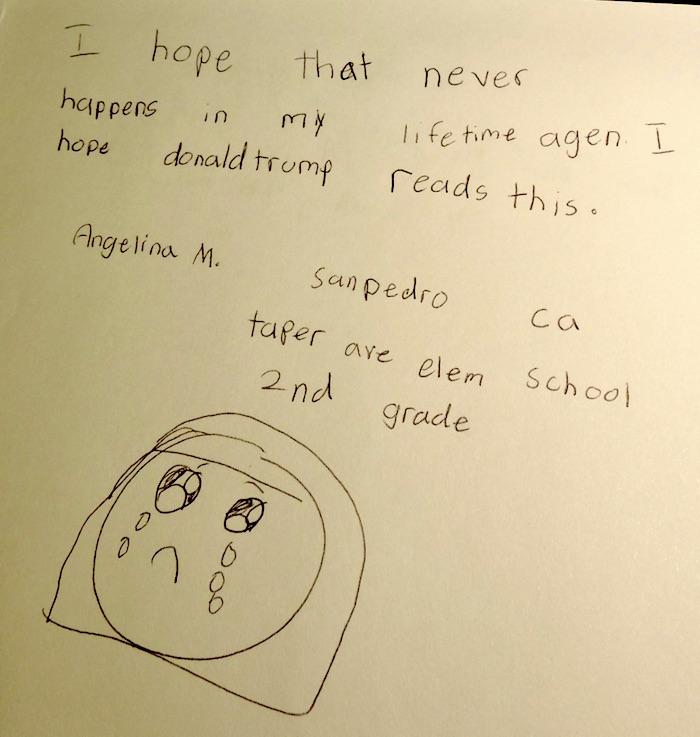

In one of the barracks, visitors may push buttons and listen to voices of real people who once lived and experienced Manzanar. I watched a woman listening and wiping tears from her eyes. When I listened, I had to wipe my eyes, too. I spent a long time turning pages in that big book where visitors are invited to write and gave thanks that I saw note after note from other Americans — apparently of all colors and heritages — who were disgusted and ashamed after they had wandered and read the words and looked at those countless photos on panel after panel of displays. It’s good to know there’s a sense of alarm out there now — at a time when some people in power are trying to fan and use fear of other people to support whatever their goals may be.

This is a place that obviously touches the hearts and minds and consciences of many thoughtful people. It’s a powerful antidote for ignorance that fuels the stupidity of fear and hate.

And that, to my simple mind, is a wonderful thing to behold.

As long as the world lasts there will be wrongs, and if no man rejected and no man rebelled, those wrongs would last forever. — Clarence Darrow

Comments

My favorite subject in school was of history, particularly, California history. As an adult, I travelled across California, taking home photos, and books, and memories. On one such trip, I traveled north on US 395 from Los Angeles, and pulled off the road at a historical marker at the place called Manzanar. As I read, I was puzzled. What were they talking about? What Japanese interment camps? I had never heard of that bit of U.S. History.

I remember glancing around me at the barren, windblown high desert, with the gorgeous eastern Sierras in the distance, and wondered what this was all about. This was in 1982, and all there was of Manzanar back then was the burial monument at the end of a gravel driveway. No relics, no restorations, no visitor centers--nothing. I later stopped at a place in Independence, CA, down the road a few miles, that had numerous displays of the camp. I bought several books about the region, and about Manzanar, and read as much as I could.

When I think of Manzanar, I think of the Japanese Americans, and their non-citizen parents and grandparents, who had everything confiscated from them, then were loaded onto buses and trains, and hauled off to the most god-forsaken places in the country. They were brave people who exhibited patience, and courage, and a determination to survive despite the odds. Their sons, highly decorated U.S. soldiers, bravely fought, and many died for, the very nation that betrayed them.

I still feel outraged that such a significant piece of our American history would be left out of the classroom.

It's been a few years since my latest trip to Manzanar, and I anticipate the restorations and other interpretive displays now available.

The victims of WWII were not the internees, whose families were kept intact and cared for. The victims were those who were forcibly sent to war to suffer and die, and those who had to endure the hardships and sacrifices on the home front. This is a gross misunderstanding of history which is perpetuated by the NPS. You get satisfaction by calling your parents and grandparents racists? You will get similar treatment when your grandchildren judge you for destroying their planet.

Rob--

Speaking for myself, no I don't get _satisfaction_ from stating that my dad's parents were racists (not just about Japanese during WW2, but into the 1960s when I knew them), but I don't deny or lie about it either. I can be proud of other aspects of who they were and what they did, but I can acknowledge aspects of them I am not proud of.

From my perspective, it is your "history" that is a gross misunderstanding. Native born and naturalized US Citizens of Japanese ancestry lost their lands and their possessions, and were forcibly shipped off to camps in the harshest areas of the intermountain west. [Non-citizen residents of Japanese ancestry, too.] The vast majority from Southern California lost everything and were never able to return here after the war. Some from Seattle and the San Francisco Bay area were able to return to those areas after the war (see Minidoka on Bainbridge Island), but they still lost nearly all of what they had as well as the years spent locked up in the camps.

What is this "cared for" you speak of? The internees had to farm in those harsh conditions for much of their food; they had shops to try to build basic furniture. Their hardships and sacrifices were much greater than that of my grandparents, aunts, & uncles (on both sides of my family) on the home front. Those in my family too old or too female to fight worked in shipyards and aircraft factories, but were able to buy houses and get paid good salaries and go to occasional dances. I'm proud of their contributions, sacrifices, and hardships, but their fellow citizen internees had greater hardships and sacrifices on the home front.

Despite their treatment, many of the young men in the camps signed up for the 442nd, then suffered high casualty rates in part because they felt that they had to prove to people like you that they were as patriotic and loyal US citizens as any other citizens. How does that not qualify as your "suffer and die", because they weren't drafted? Many other US Citizens volunteered before they would have been drafted, so they, too, weren't "_forcibly_ sent to war" if that is your criterion. I respect and honor all of those who fought for us, no matter their ancestry or citizenship status.

I'm a natural resources wild lands kind of guy, but I am very happy that NPS has Manzanar and Minidoka and soon Honouliuli as well as Rosie the Riveter, Port Chicago, Valor in the Pacific, War in the Pacific, American Memorial, and the WWII Memorial in the Mall. They are all aspects of our heritage from that era, preserved for ourselves and future generations.

To liken the internment of US Citizens who broke no law to caring for children who either independently or abetted by their parents/relatives illegally entered the US is a massive disservice to the true injustice to the former.

EC--

While I suspect you and I probably disagree about the morality and appropriateness of separating detainee children from their parents even for those requesting asylum, we agree that is very different than the subject of this post.

However, I don't see anyone here likening the two. I re-read Lee's post from June 8, well before the current wave of news interest and outrage. He mentions more general anti-immigrant sentiment and policies over the decades, but he doesn't mention the current issue of childhood arrivals. I didn't mention it. If you were worried/offended by my honoring all those who fought for us irrespective of their ancestry or citizenship status, that's not about Mexican Americans. I was actually thinking of the many Filipinos who fought with us in WW2, and ended up in San Diego; I grew up and went to school with their (US born) children.

I didn't respond to Ron's final line, but I will now. If future generations hold me in contempt or scorn because of the current immigrant and asylum policies, that may be deserved. [On planet destruction: I work hard to minimize & mitigate ecosystem destruction, carefully separating on the clock from off the clock activities, so on that topic they may judge me a failure, but they can't say I ignored it or didn't try.]

https://www.cnn.com/2018/06/19/politics/george-takei-family-separation-o...

tomp2,

It is good that NPS has sites to tell the WWII stories. The problem is that the interpretation is done by looking at history from today's perspective, and not from the perspective of those who lived it.

To truly understand history one has to understand all the aspects of living in that time. It takes much study of life in that era. WWII suddenly transformed every aspect of life, and profoundly affected everybody. And it should go without saying that they didn't have the time machine into the future like we do.

Anyone who says the Japanese were interned for racial reasons has not done their homework. They are simply making a social justice judgment, as is so popular in today's culture. You might also think we fire bombed Tokyo and nuked Japan for racial reasons.

Many internees were proud to do their part for the war effort. Yes they made sacrifices, as did everybody else.

Go read National Geographic from 1940 to 1942 to see what people saw who didn't know the future. Nobody wanted the war, but they rose to the occasion. It was not about racism.

The Manzanar displays distort history to fit today's culture. So people go away like you did, with no sense of what really happened. And, as we see in this thread, people are so quick to mindlessly tie it into current headlines.

You may think you are doing the best you can for the environment today, just as our parents did the best they could to fight WWII. But your grandchildren will condemn you anyway. Their perspective in the future will be much different from yours today.

tomp2 - You do not see anyone likening the two? Did you not see the picture at the end of the story? If you think Lee submitted this at this time for any other purpose than to liken the two you are very naive.