Onward to Fort Clatsop, Louis and Clark National Historical Park / Rebecca Latson

“Historical” versus “historic”: according to Merriam-Webster.com, “historical” is a general term for describing history, and “historic” is “usually reserved for important and famous moments in history.”

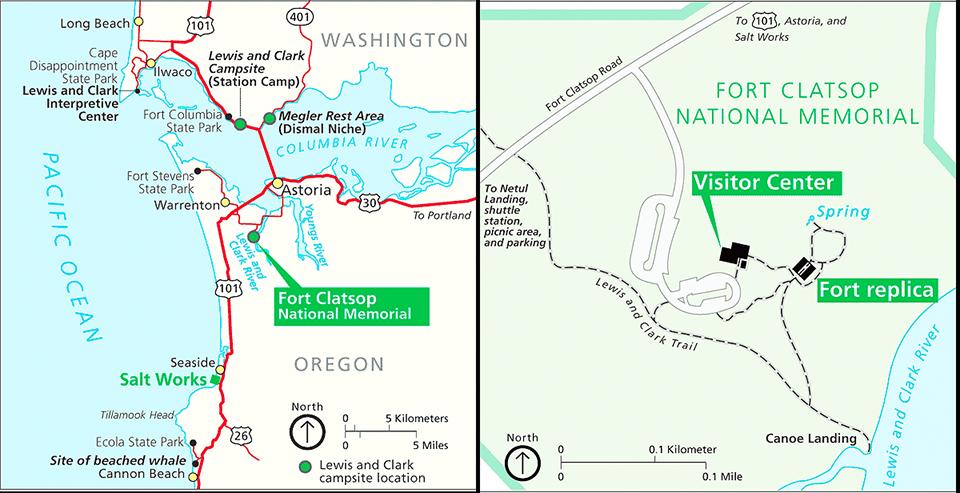

Lewis and Clark National Historical Park and Fort Clatsop maps / National Park Service

I’d discovered Fort Clatsop and Lewis and Clark National Historical Park while looking at a Google Map display of Ilwaco, Washington and Astoria, Oregon. I knew I’d be in that general area in early December 2021 while following along the Pacific Northwest portion of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail (you’ll be reading about my photo expeditions in upcoming articles) and figured a visit might be worthwhile. I should note that while Fort Clatsop is not all there is to this national historical park, I was under time constraints and thus explored only the fort and its immediate surroundings. That’s the focus of this column, including a little history along with examples of images you can capture for yourself during a visit to this small fort next to the Lewis and Clark River (aka Netul River) in Oregon.

It’s one thing to read a book about historical buildings and sites, but it’s another thing to physically see for oneself where these people of the past spent their days, the ground they trod, and the environment in which they lived. Fort Clatsop was the Lewis and Clark 33-member Corps of Discovery’s winter encampment from December 1805 to March 1806. If you’ve ever visited the Pacific Northwest’s coastal landscapes during winter or spring, then you’ll have some idea of the seemingly constant cold driving rain and stormy weather experienced by the expedition members. This was no Four Seasons Resort. It was built under wet, cold circumstances with an occasional clear, dry(ish) day or two thrown in. Fleas and mosquitoes besieged them, they were often sick, and no glass for windows created damp and drafty living conditions in the small rooms during that winter sojourn with no Gore-Tex, fleece, rain boots, or any 21st-century luxuries to keep them comfortable. At some point during their stay, Meriwether Lewis did notice, appreciate, and ultimately purchase made-to-order conical rainhats constructed of tightly-woven cedar bark and beargrass from the local Clatsops, a tribe of Chinook-speaking Native Americans living in villages “on the southern side of the Columbia River and south down the Pacific Coast to Tillamook Head.” These hats efficiently shed rainwater and kept heads relatively dry.

During their winter and early spring stay, the Corps members hunted, gathered firewood, made salt by evaporating the ocean water near the present-day town of Seaside, fashioned tallow candles rendered from elk and deer fat, tanned hides for clothing, and prepared for the day they would begin their return journey to home and civilization. They also wrote in their journals, copied that writing into other journals, and worked on maps – all by the light from campfires and tallow candles.

So, let’s think about how you might photograph the fort and nearby landscape to give your viewers a feel for the place. As you approach the fort (a replica based upon a diagram by William Clark as well as archaeological evidence), you’ll probably notice the fort’s small size. Definitely not as large as, say, the fort and surrounding buildings at Fort Laramie National Historic Site in Wyoming. Fort Clatsop was just large enough to house the enlisted men, captains, and civilians (including Sacagawea, her French-Canadian husband Toussaint Charbonneau, and their infant son Jean Baptiste), with a storage room for food and other supplies.

Approaching Fort Clatsop, Louis and Clark National Historical Park / Rebecca Latson

This overall small size works to your wide-angle lens’ advantage, actually, so think about how you want to frame your composition. Should you approach from an angle, like the image above, and/or use the open gates as natural frames like the image below?

Welcome to Fort Clatsop, Louis and Clark National Historical Park / Rebecca Latson

Even on a sunny day, the fort will be shaded by the surrounding trees, so you’ll need to bump up your ISO to between 500 – 640 if you are handholding your camera (which is what I did) to maintain a fast enough shutter speed to avoid camera shake blur. If you use a tripod, then you can keep the ISO at 160 – 250 while using a much slower shutter speed.

After you’ve captured an overall view of the fort, why not now try to get a shot of one of the interior rooms. They’ll be pretty dim to downright dark, so if you don’t have a flash on your camera, you’ll need to increase the ISO and open up your aperture as wide as possible. For the image above, my ISO was 2000 with an aperture opening of f4.0.

Barrack interior, Fort Clatsop, Louis and Clark National Historical Park / Rebecca Latson

How do you want to frame your interior room shot(s)? Do you want to stand in a corner of the room or capture a photo looking through the door or perhaps stand in the room looking out the door? Each of these suggestions require not only thought in framing your photo, but also selecting correct exposure settings. If you are handholding your camera under low light conditions with no flash, then keep that shutter speed around 1/30 – 1/40 and use the burst method of holding down that shutter button for several clicks. At least one shot should (hopefully) be nice and clear with no camera blur. In retrospect, I wish I’d brought my small flash with me.

Those interior images might be on the noisy (grainy) side, so you’ll probably need to use some noise reduction software like Imagenomic’s Noiseware or Topaz Lab’s DeNoise AI or ON1 NoNoise AI or whatever noise reduction is included with your regular photo editing program.

Map of Fort Clatsop and trails, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park / National Park Service

A boardwalk trail down to the Netul River, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park / Rebecca Latson

Among the 14.5 miles of trails within this national historical park, there is a trail from the fort down to the Lewis and Clark River (known by the locals as the Netul). After you’ve investigated the fort, take some time and at least walk to that first view area along the boardwalk overlooking a part of the river. While a wide-angle lens will capture the entire scene, don’t forget to use your telephoto lens or telephoto setting, too. You might see a pileated woodpecker, a purple martin, or even a river otter.

A view beyond the trees to the river, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park / Rebecca Latson

Trivia: According to the NPS educational plaque at the view area where the image above was captured, "those distant poles or "piling" (sic) you see sticking out of the water in the image are from 80-year old Douglas firs used during log sorting and raft making. Those log poles were embedded 20 feet into the river bottom and could be a maximum length of 60 feet."

If you visit this national historical park during peak season (summer months), you’ll see rangers dressed in buckskins offering “demonstrations such as flintlock gun shooting, hide tanning, and candle making.” Demonstrations like those provide insight into the daily life and chores performed by the expedition members during those few (monotonous) months spent at the fort. Definitely take the time to wander around the visitor center’s museum and watch the film narrating the Corps of Discovery’s explorations.

A statue of Sacagawea and her infant son along the trail to the fort, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park / Rebecca Latson

The National Park Service manages the Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, so you can use whatever national park pass you possess in addition to any of several other park passes . If you don’t have a pass, then the cost is $10/person valid for seven days (those 15 years and younger get in free).

References

Anthony Brandt (Editor), The Essential Lewis & Clark, 2002, National Geographic Partners, LLC

Stephen E. Ambrose, Undaunted Courage | Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, And The Opening Of The American West, 1996 (2005 paperback edition), Simon & Schuster Paperbacks

http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/1011

http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/331

https://www.nps.gov/lewi/learn/historyculture/histcult-people-tribes.htm

Comments

Thank you for the education and great pictures of this historic place. . . . and suggestions of how to photograph them. Might have to be on my list of places to "check out".

super cool!!