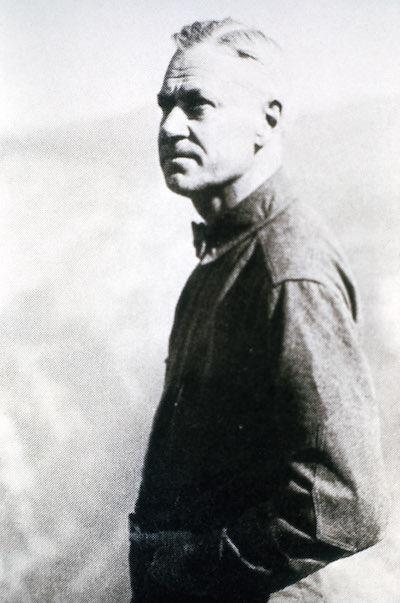

The next director of the National Park Service should bring many of the same traits exhibited by Newton Drury, Horace Albright, George Hartzog, and Connie Wirth (L to R)/NPS

Editor's note: Jonathan Jarvis, the 18th director of the National Park Service, retired today. Who will be his successor? Harry Butowsky, a retired National Park Service historian, outlines some qualities needed in the agency's 19th director.

In 2017, the National Park Service begins not only a new year but also a new era with new leadership. The National Park Service finished its first 100 years with many examples of excellent leadership and, unfortunately, some examples of poor or no leadership.

The past seven years have been hard on the National Park Service. Our agency has been beset by low morale, a continued lack of adequate funding that goes back to the last century, a growing maintenance backlog, sexual harassment scandals, overcrowding in our national parks, fraud by at least one regional director, and an inability to turn the centennial of the National Park Service into a solid foundation upon which to base the next 100 years.

What is needed now is leadership of the type the National Park Service has not experienced for the last generation.

Many of our previous directors, beginning with Stephen Mather and Horace Albright, are now legendary. Mather and Albright established the National Park Service on a firm foundation and gave it life. Their policies and examples have served the agency well over the last century. They understood the importance of history and used history to give life to the National Park System.

These men were followed by Newton Drury, Connie Wirth, George Hartzog, Russell Dickenson, and James Ridenour. Each took on the problems of the day to enrich the service. They each passed to the next generation of Americans a National Park System in better condition then when they received it.

All had important leadership qualities. They were able to influence, motivate, and enable others to contribute toward the effectiveness and success of the National Park Service. Each had the ability to bring positive change to the agency. They were all men of substance and accomplishment with long careers before they became the director of the National Park Service.

During the Wilson administration in 1915, Interior Secretary Franklin K. Lane was perfectly willing to pick a Republican outsider renowned for his business acumen to launch the service. Lane picked Mather, a successful businessman then at the pinnacle of his private career — a man of vision and achievement. Lane knew that Mather could tackle difficult problems and achieve results.

Mather had ideas gleaned from years in the business world. He knew how to mobilize people and resources to accomplish larger aims. Lane understood this. In 1916, working with the railroads and other private groups, Mather helped lay the foundation of the National Park Service, defining and establishing the policies under which its areas were to be developed and conserved unimpaired.

Using the railroads, Mather engaged Congress with the facts. Even in 1917, tourism led by the national parks was a $500 million business. Why should the country just throw that away?

Mather knew how to spot and hire good employees. Albright was one of his first hires and worked with Mather throughout his tenure as director and went on to succeed him. Albright also was a man of vision and common sense and was able to engineer the transfer of 64 parks from the War Department to the National Park Service after meeting with President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933. He knew how to sell his idea to create a larger and more comprehensive National Park System.

Stephen Mather, a businessman, not a bureaucrat, was chosen to be the first director of the National Park Service/NPS

Today, the next director of the National Park Service needs to be as bold. Unfortunately, there is little that is bold from inside the government, since the bureaucracy will never allow it.

Today, there are multiple threats to the National Park System. There is a real threat to their future that only an outsider dare take on. Mather and Drury were not afraid to take on interests that posed a threat to the National Park System.

Drury was an outsider, first serving 20 years as executive secretary of the Save-the-Redwoods League prior to becoming National Park Service director. Born in Berkeley, he was the third Californian, after Mather and Albright, to lead NPS. His term was perhaps the most critical NPS has seen. Drury turned back incessant demands to use the parks for mining, grazing, logging, and farming under the guise of wartime or post-war necessity. In spite of intense political pressure, Drury protected the parks and kept them inviolate.

Wirth also grew up in a park environment — his father was park superintendent for the city of Hartford, Connecticut, and later the city of Minneapolis. Wirth took a degree in landscape architecture from what is now the University of Massachusetts. He first came to the Washington, D.C., area to work for the National Capital Park and Planning Commission. Albright had him transferred into NPS, where he was put in charge of the Branch of Lands. He went on to supervise the Interior Department's Civilian Conservation Corps program, nationwide. As director, he won President Eisenhower's approval of a 10-year, billion-dollar Mission 66 park rehabilitation program. Mission 66 remains today the largest and most important fiscal achievement to improve the infrastructure of the National Park Service.

Hartzog, in the years leading up to his tenure as director, was a ranger at Great Smoky Mountains National Park and superintendent of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial National Historic Site in St. Louis, where he spearheaded the project for Eero Saarinen's Gateway Arch.

As director, he served as Stewart Udall's right arm in achieving a remarkably productive legislative program that included 62 new parks, the Historic Preservation Act of 1966, and the Bible amendment to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act that led to the establishment of the Alaska parks. Much of the nature and scope of the National Park Service today owes its creation to the vision of Hartzog.

Dickenson was a Marine Corps veteran who worked his way up through the NPS ranks. Dickenson held a variety of positions within the National Park Service — before ascending to the directorship in May 1980. Having risen through the ranks and enjoying the respect of his colleagues, Dickenson restored organizational stability to the Park Service after a succession of short-term directors. He obtained its support and that of Congress for the Park Restoration and Improvement Program, which devoted more than a billion dollars over five years to park resources and facilities.

Ridenour came from outside the National Park Service. He was formerly head of Indiana's Department of Natural Resources and served as director during the Bush administration (1989-1993).

Doubting the national significance of Steamtown and other proposed parks driven by economic development interests, he spoke out against the "thinning of the blood" of the National Park System and sought to regain the initiative from Congress in charting its expansion. He also worked to achieve a greater financial return to the Park Service from park concessions. In 1990, the Richard King Mellon Foundation made the largest single park donation yet: $10.5 million for additional lands at the Antietam, Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, and Petersburg Civil War battlefields, Pecos National Historical Park, and Shenandoah National Park. Ridenour also warned us of the dangers of too large and rapid expansion of the system.

All of these men exhibited leadership and were not only able to identify challenges faced by the National Park Service but were able to solve these challenges. They were men of knowledge and substance. They had the courage of their convictions and were not afraid to do what was right and good for the National Park Service.

A word about their opposites, then, the politically-inclined directors who have directed the National Park Service for the last generation. We just suffered through our last. Sure, they know what we want to hear. The point is that they tell everyone what they want to hear. They take no stands; they take no risks. Like the worst of our political appointees, they believe in going along to get along. They have devastated the morale of our employees.

The National Park Service now faces new challenges. For example, in 2009, the National Parks Second Century Commission report stated the following:

“National parks are among our most admired public institutions. We envision the second century National Park Service supporting vital public purposes, the national parks used by the American people as venues for learning and civic dialogue, as well as for recreation and refreshment. We see the national park system managed with explicit goals to preserve and interpret our nation’s sweep of history and culture, sustain biological diversity, and protect ecological integrity. Based on sound science and current scholarship, the park system will encompass a more complete representation of the nation’s terrestrial and ocean heritage, our rich and diverse cultural history, and our evolving national narrative. Parks will be key elements in a network of connected ecological systems and historical sites, and public and private lands and waters that are linked together across the nation and the continent. Lived-in landscapes will be an integral part of these great corridors of conservation.”

Fine, but each of these goals is a minefield, just as similar goals were to Mather and Albright.

In order to accomplish these goals, new leadership is needed to inspire the employees of the National Park Service and to reconnect with the American people. This leadership will need strong managerial traits. They are the same traits used by the Mather, Albright, Drury, Wirth, Hartzog, Dickenson, and Ridenour.

These traits are the ability to focus on outstanding problems, exhibit confidence in solving issues, use transparency in all respects, have integrity, offer inspiration, and, above all, show a passion for your work.

With the exception of some great and innovative National Park Service directors such as Hartzog and Dickenson, you don’t give that agenda to a bureaucrat to solve. True innovation usually comes from outside of the government. It comes from a Mather, an Albright, or a Drury. As John F. Kennedy discovered when speaking of the State Department, it was like a bowl of Jell-O. When you kicked it, it jiggled a lot, and then settled right back into place.

The question is where to look for a new director who knows that. Anyone can talk about vision, but few can get it done. I believe the new director must come from the private sector outside of the ranks of the National Park Service and federal government. Given the poor quality of leadership the National Park Service has suffered for the last generation, an infusion of new blood is critical. Only an outsider will be able to secure the agency’s confidence after decades of lackluster appointments. We need a new beginning. We need a person with a fresh outlook and new ideas.

The next director will have to focus a laser beam on the huge maintenance backlog and lack of adequate staffing in our parks. He/she will have to inspire confidence among our employees that their solutions will solve our problems. Every decision he/she makes must be transparent and be explained to the employees of the National Park Service. He/she must inspire everyone to do his/her best in the performance of duties and exhibit a passion for the parks and the core natural and cultural values they contain.

He/she must inspire an atmosphere of innovation where employees can contribute ideas to improve the management of their parks and, finally, he/she must have the patience to work out difficult issues that are complex and not subject to immediate solution.

I believe our next director must have the qualities and talents of Mather. Our next director should have a record of accomplishment in business or some other aspect of the private sector. Our next director should have no ties with the agency but be free to look at the agency with a fresh perspective to decide what must be done.

Our next director must be a problem solver. Our next director must give the National Park Service and System a new beginning. He/she must have the patience to work out difficult issues that are complex and not subject to immediate solution.

And yet, the incoming director should also realize and appreciate the wondrous resources – natural, cultural, historical – held within the National Park System and be committed to seeing they remain unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.

In 2017, we have a chance to begin again and start the next hundred years of the history of the National Park Service with as strong of a leader as Mather and Albright demonstrated in the founding years of the National Park Service. We need to build a firm foundation to do this.

The National Park Service needs the best leadership available. The American people and the thousands of hard working and loyal NPS employees deserve no less.

Comments

Al, it would be nice if your comments weren't so patronizingly pedagogical. This is a discussion. Trying to be civil. I haven't paid tuition to be talked down to and given reading assignments, and as far as I know you haven't been an active professor for quite a while. Many of my habits were formed during the 30 years I was a healthcare professional, but in common fora like this I try to avoid most of the stilted medicalese and such from those days. Please?

Did Mr. Jarvis can Mr Caldwell ????

I can only hope that the Trump administration will put so much thought into the selection as that which has gone into this article and the comments. For good or bad, the administration's needs and expectations will override the hopes and aspirations of us national park travelers. Nice work, Harry B.

I agree with pretty much everyone here that there aren't any obvious internal candidates for NPS director, and that even if there were, NPS is in the phase of the cycle where an outsider coming in as director would be beneficial. We have a lot of crap that needs to be cleaned up, and a lot of ossified patterns that need to be examined and broken. Contra Dr. Runte, I think there are times when an insider with knowledge of the ranks & processes is needed as director, if for no other reason than to consolidate the improvements from the preceeding outsider. This is not that time.

But, outsider isn't enough. I've never heard anyone say that the most recent director that came from outside NPS improved the service. I think we currently need an outsider who understands and values the mission of the NPS, and both has new ideas for accomplishing that mission and can advocate effectively for that mission. I don't think that they need to know the Vail Agenda; I think that they need to be able to read and understand and react to the Vail Agenda, and Leopold I & II, and 1 or 2 other big vision documents. I think that's what Rick's first comment is about, needing someone from outside who understands what the service is about and for and makes that better, instead of trying to change the mission of the service.

I find Michele's post interesting and informative. I'm a different kind of professional in a different part of NPS, and the part around me isn't as much a cult or cult of personality of the "Ranger". But I've certainly seen glimpses of what she mentions, and don't for a second doubt her description of her part of NPS and likely most of NPS.

"We have a lot of crap that needs to be cleaned up" and that is precisely why our President Elect is Mr. Trump. The present POTUS and others in power have had their chance and things have gotten progressively worse, on all counts. Someone that has actually succeeded at something in the real world might just be what NPS and every other agency at the National Level needs. Try not to be to disappointed if he succeeds. Me thinks that is the fear of more than just a few. I am from a family that these wild places have played and continue to play a big part in our lives. I am actually optimistic that there can be a righting of the ship to something that has some semblance to real.

Al--

As long as we're giving out reading assignments, please re-read Harry's block-quote from the Second Century Commission Report. He's right: each of those sentences is a minefield. They require some understanding of science, scholarship, and conservation (biological and cultural), and a willingness to engage with experts and apply the best (imperfect) knowledge of each of those issues in the furtherance of the mission. While some CEOs and investors (and historians and scientists, for that matter) may have that skillset, most don't.

A director who thinks that climate change is a hoax by China will not be able to address any of those issues or goals, no matter how wonderful of a businessperson or manager they might be. Someone who thinks that parks could function ecologically as islands, with sufficient fences on the boundaries and complete development outside the boundary, is not going to make good decisions about bison and pronghorn and bats and birds. In this age of shifting species ranges, they could be disastrous for the "wild life therein" mentioned in the organic act. [For all his myriad other shortcomings, Jarvis mostly understood when experts explained natural resource issues to him, even though I disagree with some of his subsequent decisions.] In addition to getting our NPS house in order, the next director needs to build cooperation and collaboration with FWS, USFS, BLM, DOD, tribes, and other land management agencies.

The more fundamental question for NPS natural resources is what does "unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations" mean for natural resource parks in the face of not just climate change, but deposition, introduced species, altered fire regimes, and encroaching / surrounding development and land conversion (to say nothing of visitor pressure)? Given the (moderate but pervasive) landscape alteration of Native Americans before European settlement, the philosophical question used to be "vignettes of when": before European settlement, 1800, the date of park establishment, some mythical "pristine" nature before Native American impacts (but post Pleistocene)? [I vaguely recall something from Al in NPT about Cronan's "The trouble with wilderness" applied to stopping industrial-scale solar energy on BLM lands in the Mojave Desert at Ivanpah or Soda Mountain. I missed his point: while I would have preferred the solar plants go in other areas already more trashed by mining & military training, I've _walked_ those areas and they weren't wilderness by any definition, and both sites are well outside the Mojave National Preserve boundary.]

That's all moot: the world is changing out from under parks, and while managing for conditions on a specific date is difficult for cultural parks like Gettysburg (forest succession prevents forest blocks from remaining in the 1863 condition), it's impossible for natural resource parks. I don't think that the answer is that all possibilities are equal, so auction off 15 parks to make Disneylands and Jellystones as amusement parks (c.f. Pombo circa 2005). Rather, I think a good answer will require hard thinking and consensus about what we want to pass down to future generations, and what science tells us is possible or plausible. Again, I want the next director to come from outside of NPS, but I want someone who can frame and understand and communicate and address such questions.

In terms of parks preserving and interpreting our cultural heritage, I don't know the major issues. But I want someone who values both units of Valor in the Pacific, who realizes that the story of our wonderful country has more richness than just forts and battlefields and presidents and conquerers.

I'm reserving judgement on the next director until someone is named, but until then I'm more fearful than hopeful. I will be very happy to be proven wrong in that fear. But while looking for previous year's NPT articles on "Best places to work" surveys I got sidetracked by some articles from 2006. Yes Donald Trump is not _that_ kind of Republican, and Pombo is no longer in the House, but I think Al has forgotten what pressures were on NPS under the GW Bush administration.

I read the full McFarland paperAL linked (yea archive.org!). My limited perception of the spearheads of the founding of NPS centers on the Mather Mountain Party and the UC Berkeley connection; I didn't know much of J. Horace McFarland (as opposed to Peter C. Mcfarlane of the Saturday Evening Post in the Mather party). Accounting for the flowery language of the time, I found much I agree with, especially the sentiment that accomodations should be government at cost instead of private concessions: "Business is to get all you can for what you give, and service is to give all you can for what you get." However, McFarland's paper doesn't give any indication he understood a sense of place the way Muir and TR and Mather and Albright and Olmstead and Leopold did. To him National Parks differ from city parks and playgrounds and rec centers in spatial and temporal scale of play, but aren't specific heritage. At it's best, NPS is about preserving our heritage of natural and cultural objects, of specific places, for the enjoyment of future generations.

Harry Butowsky's piece has the wrong problem. Harry Butowsky also has the wrong solution.

And the entire piece is riddled with contradiction; he praises one Director for traits he condemns in others.

Then he rips up another Director for what he's written a hagiography for another.

The problem parks face is the ideological opposition to the environmental and preservation laws among leading Members of Congress and "not for profit" political action committees.

Butowsky seems to think all the problems with the parks are either the National Park Service or having the wrong parks.

It is not money. The amount of money parks cost is insignificant, and the cost of new parks is even more insignificant. The money is not appropriated because the ideological enemies of the parks want to starve the parks into incompetence, and then claim that the starved park service is incompetent or corrupt. That justifies further budget cuts, and the cycle goes on.

All this enables Harry Butowsky to blame the leadership of Director Jarvis for everything wrong with the parks. But Harry Butowsky is wrong that the heroes he cites faced the problems with Congress the National Park Service has now. (At least not to the extent as now; Russ Dickinson, Roger Kennedy and Bob Stanton did experience some of the sulphur, but they did not have a Congress as we have seen since the rise of the Tea Party.)

And Harry Butowsky is wrong that Jarvis did not face tough battles to defend parks, and he stood up and won. There were repeated legislative efforts to strip the national park service and other conservation agencies of the primary preservation laws. These efforts were blocked under the leadership of Jarvis and the White House.

George Hartzog never faced these kinds of challenges. Neither did Mather, a Republican appointed by a Democrat who as a Republican enjoyed bi-partisan support.

Harry Butowsky goes on and on about great leadership from Jim Ridenour, but if a Republican in a Republican Administration was so strong, then why did he allow the Republican McDade to build Steamtown, a place with no primary historical resources that relate to the location in Scranton?

And why was Ridenour rolled by the Utah Republican Senate Delegation in the creation of Weir Farm, the other place that seemed to have driven him to the remarkable insight (joking here) that the problem with the parks was the parks? How can such a 'great leader' like Ridenour be so great when what he hated as a blight for the parks just flowed in under his watch? And compared to Butowsky's other heroes, Jarvis added very little acreage to the National Park System for the two terms he served? (NB: thinking that protecting nationally significant lands is a bad idea is NOT my criterion, but depending on who he is talking about, it sometimes is the criterion for Harry Butowsky.)

And why the remarkable crediting Russ Dickinson as responsible for stabilizing the Service (huh?), also crediting Dickinson for getting a long term in office as a point of stability, but Jarvis who served longer gets no credit? And why is Jarvis seen as "political" but Ridenour was the actual Campaign Treasurer for Dan Quayle and Ridenour was awarded the job as campaign spoils?

And why give Ridenour credit for the concessions law, when the push toward concessions reform began long before Ridenour and did not pass while he was Director?

And why nothing from Harry Butowsky about the fact that the job of the Director changed when Congress in 1998 made it a Presidential Appointee? Harry Butowsky, do you really not think that is another of the numerous external conditions you ignore in this piece?

There are dozens of such examples of contradictions.

Embarrassingly, it really looks like is a personal grudge. Is it a personal rant? Harry Butowsky -- did you have a career problem for you personally from Director Jarvis? Is there some primary recommendation from you -- something not in this article -- that was rejected by Jarvis?

And Harry Butowsky, do you really think what we need will be a Director "laser-focused" on infrastructure, when the primary environmental laws are under threat, when the cheapest and best way to protect and manage parks is by buying up the land inside the boundaries, when the ranks of Ranger Interpreters -- park naturalists and park historians and community outreach interpreters -- have been so decimated, when parks already are feeling the effects of global warming on primary park resources, when Representative Rob Bishop has been systematically blocking parks from any standing to object to any public nuisance or hazard abutting the park (making parks less protected from an abutter than every other land owner in America), when the Republican Congress right now (Jan 3 2017) have developed a procedural Rule that would make federal land BUDGET NEUTRAL, which is a device that will enable Congress to give away park and public land for free? Why nothing about these challenges?

I am not a fan of everything Jarvis has done, and I think highly of several of those Harry Butowsky names. But his argument ignores the real state of things being faced by the National Park Service Director now, contradicts to oblivion what can be learned by previous Directors, and misdiagnoses the problem and the solution.

Mr. Butowsky, though I think we are using the same history, it's hard for me to arrive at the same conclusion that you have, in that an outsider and specifically one "in business or some other aspect of the private sector" would make the best possible next Director of the NPS. Here's the list:

NPS Directors:

2009-2016 Jarvis: career

2006-2009 Bomar: career

2001-2006 Mainella: Florida state parks

1997-2001 Stanton: career

1993-1997 Kennedy: Banker

1989-1993 Ridenour: Indiana DNR

1985-1989 Mott: California state parks

1980-1985 Dickenson: career

1977-1980 Whalen: career

1975-1977 Everhardt: career

1973-1975 Walker: insurance and marketing exec

1964-1972 Hartzog: career

1951-1964 Wirth: career

1951-1951 Demaray: career

1940-1951 Drury: conservationist

1933-1940 Cammerer: bureaucrat / Mather Assistant

1929-1933 Albright: attorney / career

1917-1929 Mather: businessman

The ones you most revere I've put in red (which won't show) italics. Incidentally I'd pick nearly the same magnificent seven, but I'd substitute Jarvis for Ridenour. The ones who have a background in business are in boldface and total only three (however for me to characterize Kennedy as merely being a "banker" is an oversimplication made merely in an effort to lend generous credibility to your argument). Of your seven favorite, only one, Mather, had a strong business background (arguing the same for Ridenour is a stretch because though he was a chemicals executive, he was selected for his Indiana Department of Natural Resources experience). Of your seven, three were actually the careerist bureaucrats you mistrust. Furthermore, to say Drury was an outsider is almost fair if you think it can be argued that a conservationist would be a stranger to the NPS, but it no more makes him a businessman than John Muir wasn't.

I've personally met and conversed (some more than others) with the last five NPS directors, in addition to having received many an official memo by each of their hands in my NPS email inbox over the past 20 years, and it is my personal opinion that the least effective, least competent, and most ethically questionable, of the last five, was the only outsider, Fran Mainella. Which is to say if your pro-business/outsider assertion had factual support, it is only evidenced in the distanct past and then only sporadically so at best.

It's obvious you've jumped on the Jarvis hating band wagon, but blaming him for rat-bag superintendents, and the sexist and sexual harassing pukes that dare ware our same uniform, is like saying of any of Trumps former wives, that if they had only been better partners, Trump would have been less of a philanderer. Somethings are beyond the immediate reach of a single leader of 22,000 employees occupying 10 time-zones. When Albright was "the man" the NPS was much easier to manage and shameful secrets more easily kept. Indeed Jarvis's single most outspoken goal was to make the NPS a force to study, communicate, and mitigate global climate change, and yet my park is full of climate change denialists (some more closeted than others).

So, don't assume, I’m questioning your conclusion because I have any love of bureaucracy. If there's one reason I will also spend my next 20 years, as I did my first 20 years, stuck as a GS-9, it's because of my outspoken opposition to bureaucracy – and perhaps my posts on NPT?

Nevertheless, on the eve of a Trump administration, anybody advocating that an outsider will be good for the NPS, may claim a vision of NPS history, but is simultaneously harboring a full-blown delusion of NPS's immediate future.