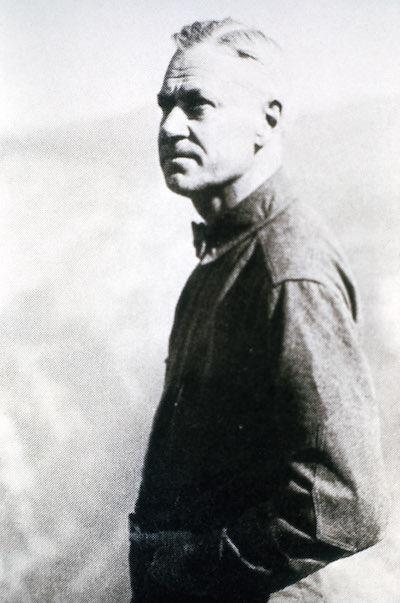

The next director of the National Park Service should bring many of the same traits exhibited by Newton Drury, Horace Albright, George Hartzog, and Connie Wirth (L to R)/NPS

Editor's note: Jonathan Jarvis, the 18th director of the National Park Service, retired today. Who will be his successor? Harry Butowsky, a retired National Park Service historian, outlines some qualities needed in the agency's 19th director.

In 2017, the National Park Service begins not only a new year but also a new era with new leadership. The National Park Service finished its first 100 years with many examples of excellent leadership and, unfortunately, some examples of poor or no leadership.

The past seven years have been hard on the National Park Service. Our agency has been beset by low morale, a continued lack of adequate funding that goes back to the last century, a growing maintenance backlog, sexual harassment scandals, overcrowding in our national parks, fraud by at least one regional director, and an inability to turn the centennial of the National Park Service into a solid foundation upon which to base the next 100 years.

What is needed now is leadership of the type the National Park Service has not experienced for the last generation.

Many of our previous directors, beginning with Stephen Mather and Horace Albright, are now legendary. Mather and Albright established the National Park Service on a firm foundation and gave it life. Their policies and examples have served the agency well over the last century. They understood the importance of history and used history to give life to the National Park System.

These men were followed by Newton Drury, Connie Wirth, George Hartzog, Russell Dickenson, and James Ridenour. Each took on the problems of the day to enrich the service. They each passed to the next generation of Americans a National Park System in better condition then when they received it.

All had important leadership qualities. They were able to influence, motivate, and enable others to contribute toward the effectiveness and success of the National Park Service. Each had the ability to bring positive change to the agency. They were all men of substance and accomplishment with long careers before they became the director of the National Park Service.

During the Wilson administration in 1915, Interior Secretary Franklin K. Lane was perfectly willing to pick a Republican outsider renowned for his business acumen to launch the service. Lane picked Mather, a successful businessman then at the pinnacle of his private career — a man of vision and achievement. Lane knew that Mather could tackle difficult problems and achieve results.

Mather had ideas gleaned from years in the business world. He knew how to mobilize people and resources to accomplish larger aims. Lane understood this. In 1916, working with the railroads and other private groups, Mather helped lay the foundation of the National Park Service, defining and establishing the policies under which its areas were to be developed and conserved unimpaired.

Using the railroads, Mather engaged Congress with the facts. Even in 1917, tourism led by the national parks was a $500 million business. Why should the country just throw that away?

Mather knew how to spot and hire good employees. Albright was one of his first hires and worked with Mather throughout his tenure as director and went on to succeed him. Albright also was a man of vision and common sense and was able to engineer the transfer of 64 parks from the War Department to the National Park Service after meeting with President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933. He knew how to sell his idea to create a larger and more comprehensive National Park System.

Stephen Mather, a businessman, not a bureaucrat, was chosen to be the first director of the National Park Service/NPS

Today, the next director of the National Park Service needs to be as bold. Unfortunately, there is little that is bold from inside the government, since the bureaucracy will never allow it.

Today, there are multiple threats to the National Park System. There is a real threat to their future that only an outsider dare take on. Mather and Drury were not afraid to take on interests that posed a threat to the National Park System.

Drury was an outsider, first serving 20 years as executive secretary of the Save-the-Redwoods League prior to becoming National Park Service director. Born in Berkeley, he was the third Californian, after Mather and Albright, to lead NPS. His term was perhaps the most critical NPS has seen. Drury turned back incessant demands to use the parks for mining, grazing, logging, and farming under the guise of wartime or post-war necessity. In spite of intense political pressure, Drury protected the parks and kept them inviolate.

Wirth also grew up in a park environment — his father was park superintendent for the city of Hartford, Connecticut, and later the city of Minneapolis. Wirth took a degree in landscape architecture from what is now the University of Massachusetts. He first came to the Washington, D.C., area to work for the National Capital Park and Planning Commission. Albright had him transferred into NPS, where he was put in charge of the Branch of Lands. He went on to supervise the Interior Department's Civilian Conservation Corps program, nationwide. As director, he won President Eisenhower's approval of a 10-year, billion-dollar Mission 66 park rehabilitation program. Mission 66 remains today the largest and most important fiscal achievement to improve the infrastructure of the National Park Service.

Hartzog, in the years leading up to his tenure as director, was a ranger at Great Smoky Mountains National Park and superintendent of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial National Historic Site in St. Louis, where he spearheaded the project for Eero Saarinen's Gateway Arch.

As director, he served as Stewart Udall's right arm in achieving a remarkably productive legislative program that included 62 new parks, the Historic Preservation Act of 1966, and the Bible amendment to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act that led to the establishment of the Alaska parks. Much of the nature and scope of the National Park Service today owes its creation to the vision of Hartzog.

Dickenson was a Marine Corps veteran who worked his way up through the NPS ranks. Dickenson held a variety of positions within the National Park Service — before ascending to the directorship in May 1980. Having risen through the ranks and enjoying the respect of his colleagues, Dickenson restored organizational stability to the Park Service after a succession of short-term directors. He obtained its support and that of Congress for the Park Restoration and Improvement Program, which devoted more than a billion dollars over five years to park resources and facilities.

Ridenour came from outside the National Park Service. He was formerly head of Indiana's Department of Natural Resources and served as director during the Bush administration (1989-1993).

Doubting the national significance of Steamtown and other proposed parks driven by economic development interests, he spoke out against the "thinning of the blood" of the National Park System and sought to regain the initiative from Congress in charting its expansion. He also worked to achieve a greater financial return to the Park Service from park concessions. In 1990, the Richard King Mellon Foundation made the largest single park donation yet: $10.5 million for additional lands at the Antietam, Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, and Petersburg Civil War battlefields, Pecos National Historical Park, and Shenandoah National Park. Ridenour also warned us of the dangers of too large and rapid expansion of the system.

All of these men exhibited leadership and were not only able to identify challenges faced by the National Park Service but were able to solve these challenges. They were men of knowledge and substance. They had the courage of their convictions and were not afraid to do what was right and good for the National Park Service.

A word about their opposites, then, the politically-inclined directors who have directed the National Park Service for the last generation. We just suffered through our last. Sure, they know what we want to hear. The point is that they tell everyone what they want to hear. They take no stands; they take no risks. Like the worst of our political appointees, they believe in going along to get along. They have devastated the morale of our employees.

The National Park Service now faces new challenges. For example, in 2009, the National Parks Second Century Commission report stated the following:

“National parks are among our most admired public institutions. We envision the second century National Park Service supporting vital public purposes, the national parks used by the American people as venues for learning and civic dialogue, as well as for recreation and refreshment. We see the national park system managed with explicit goals to preserve and interpret our nation’s sweep of history and culture, sustain biological diversity, and protect ecological integrity. Based on sound science and current scholarship, the park system will encompass a more complete representation of the nation’s terrestrial and ocean heritage, our rich and diverse cultural history, and our evolving national narrative. Parks will be key elements in a network of connected ecological systems and historical sites, and public and private lands and waters that are linked together across the nation and the continent. Lived-in landscapes will be an integral part of these great corridors of conservation.”

Fine, but each of these goals is a minefield, just as similar goals were to Mather and Albright.

In order to accomplish these goals, new leadership is needed to inspire the employees of the National Park Service and to reconnect with the American people. This leadership will need strong managerial traits. They are the same traits used by the Mather, Albright, Drury, Wirth, Hartzog, Dickenson, and Ridenour.

These traits are the ability to focus on outstanding problems, exhibit confidence in solving issues, use transparency in all respects, have integrity, offer inspiration, and, above all, show a passion for your work.

With the exception of some great and innovative National Park Service directors such as Hartzog and Dickenson, you don’t give that agenda to a bureaucrat to solve. True innovation usually comes from outside of the government. It comes from a Mather, an Albright, or a Drury. As John F. Kennedy discovered when speaking of the State Department, it was like a bowl of Jell-O. When you kicked it, it jiggled a lot, and then settled right back into place.

The question is where to look for a new director who knows that. Anyone can talk about vision, but few can get it done. I believe the new director must come from the private sector outside of the ranks of the National Park Service and federal government. Given the poor quality of leadership the National Park Service has suffered for the last generation, an infusion of new blood is critical. Only an outsider will be able to secure the agency’s confidence after decades of lackluster appointments. We need a new beginning. We need a person with a fresh outlook and new ideas.

The next director will have to focus a laser beam on the huge maintenance backlog and lack of adequate staffing in our parks. He/she will have to inspire confidence among our employees that their solutions will solve our problems. Every decision he/she makes must be transparent and be explained to the employees of the National Park Service. He/she must inspire everyone to do his/her best in the performance of duties and exhibit a passion for the parks and the core natural and cultural values they contain.

He/she must inspire an atmosphere of innovation where employees can contribute ideas to improve the management of their parks and, finally, he/she must have the patience to work out difficult issues that are complex and not subject to immediate solution.

I believe our next director must have the qualities and talents of Mather. Our next director should have a record of accomplishment in business or some other aspect of the private sector. Our next director should have no ties with the agency but be free to look at the agency with a fresh perspective to decide what must be done.

Our next director must be a problem solver. Our next director must give the National Park Service and System a new beginning. He/she must have the patience to work out difficult issues that are complex and not subject to immediate solution.

And yet, the incoming director should also realize and appreciate the wondrous resources – natural, cultural, historical – held within the National Park System and be committed to seeing they remain unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.

In 2017, we have a chance to begin again and start the next hundred years of the history of the National Park Service with as strong of a leader as Mather and Albright demonstrated in the founding years of the National Park Service. We need to build a firm foundation to do this.

The National Park Service needs the best leadership available. The American people and the thousands of hard working and loyal NPS employees deserve no less.

Comments

I just trekked out to my mailbox and came back with the latest copy of Yellowstone Forever's catalog of programs for Summer 2017. As I sat in my warm living room reading it, I was struck by the large number of outstanding learning opportunities for individuals and families to get out and EDUCATE ourselves.

This is, to my way of thinking, the kind of thing we need in ALL our national park areas, national forests, BLM and other parklands -- be they city, county, state, or federal.

I attended Wolf Week in Yellowstone last year and years earlier took my 4th and 5th grade students to Lamar for EXPEDITION: Yellowstone. I can't sing the praises of these kinds of things loudly enough.

If you haven't received your copy of Yellowstone Forever's catalog of offerings, you need to do it. RIGHT NOW!

Just go to Yellowstone.org

I would take it as a good sign if the next Director, whoever it is, meets right away with the leadership of the Coalition to Protect America's National Parks. This organization has a wealth of experience. All too often, when somebody retires all their expertise is lost. Some State agencies have limited annuitant employment programs which allows them to tap into some of this experience. An alternative is an advisory board composed of interested retirees.

About McFarland's proposal that the government take over in-park "services." Actually, the railroads were largely in favor of that, too. As they discovered, and reaffirmed repeatedly, the only profit was in their trains. Building lodges and hotels for little more than a 90-day season then set their profits back. The trains they already owned, and could shift to other markets as needed. Forced to stay put, the hotels made nothing nine months of the year.

Again, why did the railroads do it? Because that was the country a century ago. Americans were optimists; they believed in the future. They couldn't wait to sing The Star-Spangled Banner without looking to see who would "take a knee."

I see that a million women are expected in Washington, DC, come January 21. Ah, what a country! Talk about "taking a knee." Harry asks, and I applaud, that we take no more knees when it comes to our parks. Can we get there? It's up to us. Donald Trump is only the president. We are still the country if we don't "take a knee."

Alfred, por favor, will you explain to this poor addled old man what "take a knee" means? I must have missed out on that the day it was taught in the College of Hard Knocks.

Thank you Harry. This is what many of us have said in discussions amongst ourselves.

Here you go, Lee

http://www.wbur.org/onlyagame/2016/09/16/mike-pesca-kaepernick-national-...

Actually, I was hoping to keep this thread alive in response to Harry's excellent piece. As you know, it dropped off the front page several days ago. Usually, we keep a thread alive by saying global warming! I thought take a knee would be something different. Seriously, this story--and comments--have been great. Where do see this kind of dialogue anywhere else?

Oh.

Thank you, Al. I was aware of all that fooferaw but didn't connect the phrase to it.

Perhaps the entire world needs to take a knee of a slightly different kind. Drop to our knees and pray to survive the next four years. ;-}

I'll be happy if the New York Giants survive the next three hours. . .