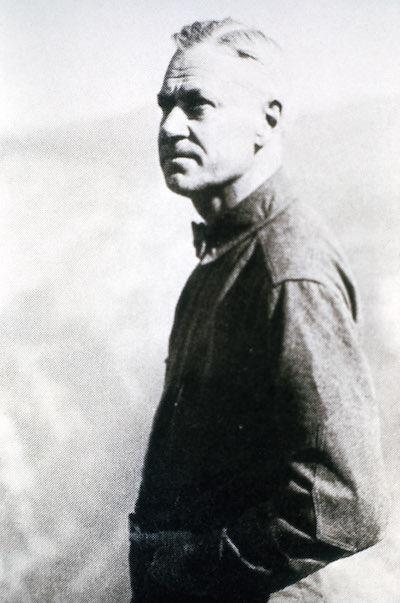

The next director of the National Park Service should bring many of the same traits exhibited by Newton Drury, Horace Albright, George Hartzog, and Connie Wirth (L to R)/NPS

Editor's note: Jonathan Jarvis, the 18th director of the National Park Service, retired today. Who will be his successor? Harry Butowsky, a retired National Park Service historian, outlines some qualities needed in the agency's 19th director.

In 2017, the National Park Service begins not only a new year but also a new era with new leadership. The National Park Service finished its first 100 years with many examples of excellent leadership and, unfortunately, some examples of poor or no leadership.

The past seven years have been hard on the National Park Service. Our agency has been beset by low morale, a continued lack of adequate funding that goes back to the last century, a growing maintenance backlog, sexual harassment scandals, overcrowding in our national parks, fraud by at least one regional director, and an inability to turn the centennial of the National Park Service into a solid foundation upon which to base the next 100 years.

What is needed now is leadership of the type the National Park Service has not experienced for the last generation.

Many of our previous directors, beginning with Stephen Mather and Horace Albright, are now legendary. Mather and Albright established the National Park Service on a firm foundation and gave it life. Their policies and examples have served the agency well over the last century. They understood the importance of history and used history to give life to the National Park System.

These men were followed by Newton Drury, Connie Wirth, George Hartzog, Russell Dickenson, and James Ridenour. Each took on the problems of the day to enrich the service. They each passed to the next generation of Americans a National Park System in better condition then when they received it.

All had important leadership qualities. They were able to influence, motivate, and enable others to contribute toward the effectiveness and success of the National Park Service. Each had the ability to bring positive change to the agency. They were all men of substance and accomplishment with long careers before they became the director of the National Park Service.

During the Wilson administration in 1915, Interior Secretary Franklin K. Lane was perfectly willing to pick a Republican outsider renowned for his business acumen to launch the service. Lane picked Mather, a successful businessman then at the pinnacle of his private career — a man of vision and achievement. Lane knew that Mather could tackle difficult problems and achieve results.

Mather had ideas gleaned from years in the business world. He knew how to mobilize people and resources to accomplish larger aims. Lane understood this. In 1916, working with the railroads and other private groups, Mather helped lay the foundation of the National Park Service, defining and establishing the policies under which its areas were to be developed and conserved unimpaired.

Using the railroads, Mather engaged Congress with the facts. Even in 1917, tourism led by the national parks was a $500 million business. Why should the country just throw that away?

Mather knew how to spot and hire good employees. Albright was one of his first hires and worked with Mather throughout his tenure as director and went on to succeed him. Albright also was a man of vision and common sense and was able to engineer the transfer of 64 parks from the War Department to the National Park Service after meeting with President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933. He knew how to sell his idea to create a larger and more comprehensive National Park System.

Stephen Mather, a businessman, not a bureaucrat, was chosen to be the first director of the National Park Service/NPS

Today, the next director of the National Park Service needs to be as bold. Unfortunately, there is little that is bold from inside the government, since the bureaucracy will never allow it.

Today, there are multiple threats to the National Park System. There is a real threat to their future that only an outsider dare take on. Mather and Drury were not afraid to take on interests that posed a threat to the National Park System.

Drury was an outsider, first serving 20 years as executive secretary of the Save-the-Redwoods League prior to becoming National Park Service director. Born in Berkeley, he was the third Californian, after Mather and Albright, to lead NPS. His term was perhaps the most critical NPS has seen. Drury turned back incessant demands to use the parks for mining, grazing, logging, and farming under the guise of wartime or post-war necessity. In spite of intense political pressure, Drury protected the parks and kept them inviolate.

Wirth also grew up in a park environment — his father was park superintendent for the city of Hartford, Connecticut, and later the city of Minneapolis. Wirth took a degree in landscape architecture from what is now the University of Massachusetts. He first came to the Washington, D.C., area to work for the National Capital Park and Planning Commission. Albright had him transferred into NPS, where he was put in charge of the Branch of Lands. He went on to supervise the Interior Department's Civilian Conservation Corps program, nationwide. As director, he won President Eisenhower's approval of a 10-year, billion-dollar Mission 66 park rehabilitation program. Mission 66 remains today the largest and most important fiscal achievement to improve the infrastructure of the National Park Service.

Hartzog, in the years leading up to his tenure as director, was a ranger at Great Smoky Mountains National Park and superintendent of Jefferson National Expansion Memorial National Historic Site in St. Louis, where he spearheaded the project for Eero Saarinen's Gateway Arch.

As director, he served as Stewart Udall's right arm in achieving a remarkably productive legislative program that included 62 new parks, the Historic Preservation Act of 1966, and the Bible amendment to the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act that led to the establishment of the Alaska parks. Much of the nature and scope of the National Park Service today owes its creation to the vision of Hartzog.

Dickenson was a Marine Corps veteran who worked his way up through the NPS ranks. Dickenson held a variety of positions within the National Park Service — before ascending to the directorship in May 1980. Having risen through the ranks and enjoying the respect of his colleagues, Dickenson restored organizational stability to the Park Service after a succession of short-term directors. He obtained its support and that of Congress for the Park Restoration and Improvement Program, which devoted more than a billion dollars over five years to park resources and facilities.

Ridenour came from outside the National Park Service. He was formerly head of Indiana's Department of Natural Resources and served as director during the Bush administration (1989-1993).

Doubting the national significance of Steamtown and other proposed parks driven by economic development interests, he spoke out against the "thinning of the blood" of the National Park System and sought to regain the initiative from Congress in charting its expansion. He also worked to achieve a greater financial return to the Park Service from park concessions. In 1990, the Richard King Mellon Foundation made the largest single park donation yet: $10.5 million for additional lands at the Antietam, Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, and Petersburg Civil War battlefields, Pecos National Historical Park, and Shenandoah National Park. Ridenour also warned us of the dangers of too large and rapid expansion of the system.

All of these men exhibited leadership and were not only able to identify challenges faced by the National Park Service but were able to solve these challenges. They were men of knowledge and substance. They had the courage of their convictions and were not afraid to do what was right and good for the National Park Service.

A word about their opposites, then, the politically-inclined directors who have directed the National Park Service for the last generation. We just suffered through our last. Sure, they know what we want to hear. The point is that they tell everyone what they want to hear. They take no stands; they take no risks. Like the worst of our political appointees, they believe in going along to get along. They have devastated the morale of our employees.

The National Park Service now faces new challenges. For example, in 2009, the National Parks Second Century Commission report stated the following:

“National parks are among our most admired public institutions. We envision the second century National Park Service supporting vital public purposes, the national parks used by the American people as venues for learning and civic dialogue, as well as for recreation and refreshment. We see the national park system managed with explicit goals to preserve and interpret our nation’s sweep of history and culture, sustain biological diversity, and protect ecological integrity. Based on sound science and current scholarship, the park system will encompass a more complete representation of the nation’s terrestrial and ocean heritage, our rich and diverse cultural history, and our evolving national narrative. Parks will be key elements in a network of connected ecological systems and historical sites, and public and private lands and waters that are linked together across the nation and the continent. Lived-in landscapes will be an integral part of these great corridors of conservation.”

Fine, but each of these goals is a minefield, just as similar goals were to Mather and Albright.

In order to accomplish these goals, new leadership is needed to inspire the employees of the National Park Service and to reconnect with the American people. This leadership will need strong managerial traits. They are the same traits used by the Mather, Albright, Drury, Wirth, Hartzog, Dickenson, and Ridenour.

These traits are the ability to focus on outstanding problems, exhibit confidence in solving issues, use transparency in all respects, have integrity, offer inspiration, and, above all, show a passion for your work.

With the exception of some great and innovative National Park Service directors such as Hartzog and Dickenson, you don’t give that agenda to a bureaucrat to solve. True innovation usually comes from outside of the government. It comes from a Mather, an Albright, or a Drury. As John F. Kennedy discovered when speaking of the State Department, it was like a bowl of Jell-O. When you kicked it, it jiggled a lot, and then settled right back into place.

The question is where to look for a new director who knows that. Anyone can talk about vision, but few can get it done. I believe the new director must come from the private sector outside of the ranks of the National Park Service and federal government. Given the poor quality of leadership the National Park Service has suffered for the last generation, an infusion of new blood is critical. Only an outsider will be able to secure the agency’s confidence after decades of lackluster appointments. We need a new beginning. We need a person with a fresh outlook and new ideas.

The next director will have to focus a laser beam on the huge maintenance backlog and lack of adequate staffing in our parks. He/she will have to inspire confidence among our employees that their solutions will solve our problems. Every decision he/she makes must be transparent and be explained to the employees of the National Park Service. He/she must inspire everyone to do his/her best in the performance of duties and exhibit a passion for the parks and the core natural and cultural values they contain.

He/she must inspire an atmosphere of innovation where employees can contribute ideas to improve the management of their parks and, finally, he/she must have the patience to work out difficult issues that are complex and not subject to immediate solution.

I believe our next director must have the qualities and talents of Mather. Our next director should have a record of accomplishment in business or some other aspect of the private sector. Our next director should have no ties with the agency but be free to look at the agency with a fresh perspective to decide what must be done.

Our next director must be a problem solver. Our next director must give the National Park Service and System a new beginning. He/she must have the patience to work out difficult issues that are complex and not subject to immediate solution.

And yet, the incoming director should also realize and appreciate the wondrous resources – natural, cultural, historical – held within the National Park System and be committed to seeing they remain unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.

In 2017, we have a chance to begin again and start the next hundred years of the history of the National Park Service with as strong of a leader as Mather and Albright demonstrated in the founding years of the National Park Service. We need to build a firm foundation to do this.

The National Park Service needs the best leadership available. The American people and the thousands of hard working and loyal NPS employees deserve no less.

Comments

Thank you d-2 for an excellent comment nicely written. A petty point perhaps, but the Yosemite Conservancy bookstore in Yosemite is quite good. As Alfred does make some good points, the population growth and sprawl issue, concern about the mega solar farms on some public lands, many others. still, I must agree with d-2, us older folks need to "advocate for the good", there is much good going on in the NPS. "Rants" are not always effective, my way or the highway usually does not work.

Rick, I believe the Chief Historian's position in the Park Service has been reduced from a GS-15 to a GS-14. I rest my case.

Because you feel your discipline was insulted and demeaned justifies you using obviously false hyperbole in an argument actually disproves your theory.

Okay, D-2, let's rumble. How many times have I heard it said that I am out of my area of expertise? Plenty. An "older frustrated male," now is it? Talk about sexist comments. How is it that "they" get to call us male, but we can't call them female? From where I sit, all that race, class, gender, and diversity have done for the Amerian experience is deepen our mediocrity, and I do mean mediocrity. Fine, celebrate the Civil Rights Movement. It was indeed part of the American experience. But don't shove it down my throat as if African-Americans, gays, lesbians, etc. alone have anything to "overcome." We all have things to overcome, and in forgetting that (which Hillary Clinton just did) we see the inevitable backlash.

I am not outside my expertise in talking about anything I talk about. I think before I write. Harry thinks before he writes. At the Park Service, he was far more than a "program manager" doing "occasionally single-minded work." He was my friend and mentor--someone I could count on for excellent advice and counsel. Over the years, his website has cut literally thousands of hours off the labor of practicing historians. Without it, we would still be spending half our day just setting up our research rather than getting straight to the materials. No, he did not have the privilege of being an academic and getting to write what he wanted, but then, no one gets that privilege anymore. It is now entirely race, class, gender, and diversity.

Am I wrong? There are still some 50 exclusive women's colleges, but men aren't allowed to have them anymore. Don't play with the facts, D-2, and call it critical thinking. It's thinking when you can tell me why anyone's civil rights can be suspended for what happened before they were born.

Have all the national parks celebrating race, class, gender, and diversity that you want. Just don't tell me that is somehow "innovative" because that is what they celebrate. They may also say, between the lines, that we are no longer allowed to have "traditional" parks. In another part of this thread, a commentator is complaining about the Park Service uniform, the agency's military heritage, and being too male. When lacking in ideas, you can always say "too male." When refusing to face the argument, you can always call it a rant. I've been there. That's the modern university, and a degree from it these days isn't worth a nickel.

Our national parks, the university of the wilderness, were always meant to be our "best idea." If today we had nothing to worry about, Harry and I wouldn't have to remind so many people what the idea really means.

Al--

I assert that northern Ivanpah Valley is not wilderness because it is chewed up by ORV tracks, enough dirt roads to not even qualify as a roadless area, and scraped rights of way for power lines and I think at least 1 pipeline. If you use google earth, go to 35.57N -115.46E, then click on the little "1994" toward the bottom to open up the date slider. You can see the roads & other features on the older imagery, but not the ORV tracks. [The golf course there is an abomination; it is there in the 2002 imagery, predating the solar site by a decade.]

There's a nice (as in solid, not as in happy) paper showing that long random straight line transects in the Mojave Desert average an ORV (mostly dirt bike) track crossing them every 50 meters. I no longer have access to electronic journals (plus I'm on AL, hence the posting during otherwise work hours), or else I'd link the paper with the data (I'd bet on Robert Webb as an author). Back when I was an academic, I spent a week walking to random points in the southern Mojave & northern Coloradoan deserts 2-10km from the nearest road to do accuracy assessment for a draft vegetation map. I can attest to similar densities of ORV tracks, even >2km from the nearest road, and both parallel and perpendicular to roads. Still, I highly recommend walking long transects as the way to understand the desert: sandy washes incised into the desert pavement versus aeolian sand tongues sitting on top of the pavement, shards from a water pot on an ancient footpath in the middle of Ward Valley. If you're out here, let's take a hike: not Encounters with the Archdruid, let alone the Mather Party, but I'm no David Brower, just a scientist.

As I wrote above, I would have preferred solar power sites in even more chewed up parts of the desert. But such sites are further away from extant transmission lines so yes, money won over conservation. These solar plants, and the solar PV sites in the western Mojave west of Lancaster, are all losses of wildness, losses of habitat. But, they have neither the short-term nor long term (centuries) impact of open pit & heap-leach mining in the same desert, or the coal strip mines on Black Mesa or up by Fossil Butte, which have even larger footprints.

I'm quite happy to tip my hat to McFarland for his role in giving me a park _service_, but I tip my hat to the others for giving me parks and "unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations" as the mission, and to George Melendez Wright for giving me natural resource programs within the service.

Amen to George M. Wright, and don't forget to tip your hat to his mentor, Joseph Grinnell. I have just revisited both of them (and others) rewriting those chapters from Yosemite: The Embattled Wilderness. To be sure, Wright's death in 1936 was a major blow to park science, as was Grinnell's death in 1939.

Now, this post I really like. It analyzes rather than just declares what you mean by lack of wilderness. You're right. All of that desert has been chewed up.

Then why continue the chewing was the point, I believe, of the California Desert Protection Act. Years ago, just before the act was passed, I met Frank and Nancy Wheat. Frank's book, CALIFORNIA DESERT MIRACLE, sits right here on my shelf. I bought it at Kelso Depot, then already seven years after the book came out.

Like Carsten Lien, the author of OLYMPIC BATTLEGROUND, Frank tells the story of hope and renewal. We have to start somewhere on the renewal of wilderness rather than simply write it off. But yes, I take your point that we should save the best first, and perhaps Ivanpah was never the best. It's just that, coming over the mountain from Searchlight, those three towers are too much for any desert, and now, along with the ORV tracks, finish off the spirit of the scenery, too.

All,

I appreciate the time and effort everyone has taken to read and comment on my Op Ed- The Qualities Needed In The Next National Park Service Director.

I think I am safe in saying that we all support the National Park Service and our fine system of National Parks and want what is best for the system. The purpose of my Op Ed was to begin a discussion concerning the qualities needed by the next Director of the National Park Service. We will have a new Director soon and I believe this person will be appointed from outside of the ranks of the NPS.

Because of this I would like to invite everyone to share with the rest of us what type of Director you think is needed at this time.

For myself, since I am a historian, I decided to think about our past Directors to see what made them successful. Thus my focus Mather, Albright, Drury, Wirth, Hartzog, Dickenson and Ridenour. Looking over the career of these men I decided that was made them successful was their shared ability to focus on outstanding problems, exhibit confidence in solving issues, use transparency in all respects, have integrity, offer inspiration, and, above all, show a passion for your work.

I believe these are the very qualities I would like to see in the next Director of the National Park Service. Now, I do not expect all the readers of this column to agree with me. Fine, I have stated my opinion and taken a position but if you do not agree with me then tell me what qualities you would like to see in our next Director. So, the purpose of this Op Ed is to generate your opinions and comments. I hope we do not start to attack each other. Let us compare notes and see if we can come up with a common position.

As I said before, we all support the National Park Service and want what is best for our parks. Let us have a civil discussion about this important issue.

Harry, we've talked about this many times. People get "promoted" and the fire dies. What I want in the next director is someone for whom the fire has never died. Perhaps what you did not mention enough in your article is that all of the people you like LOVED their work. I still have a letter in my files Horace Albright wrote me the year he turned 94. Thinking I was still in Yosemite "with the rangers," he sent it there. His purpose was to congratulate me for writing Trains of Discovery, which for him brought back wonderful memories of working with the railroads on behalf of the parks. It was typed on his old typewriter, and full of strikeovers, but no letter I have ever received moved me more.

My point: It was the last letter I ever received from a senior official of the National Park Service. From the files, which you know as well as I do, Mather and Albright never missed an opportunity to promote the agency using historians, scientists, and journalists. Where is the fire now? I don't see it, nor do I feel it, nor does Kurt feel appreciated for all his work. Calls are not returned and emails and letters not answered. That NEVER happened under the founders you write about.

Of course, it is just as bad today with the politicians. A month ago, I wrote a letter to all nine members of the Seattle City Council, and never heard back from a one. For all of our tweeting, twittering, and chatting, you mean there is no time left for a formal response?

It's in the formality--the deliberation--that we decide what is really needed. You told me you wrote 13 drafts of this article. I believe it, because it shows. The next director of the Park Service should insist on formality. Don't react. Rather, think it out.

In major universities, we now have 400 bureaucrats for every 1,000 students, there to ensure that everyone thinks alike. The consequence is to have lost the teachers, now 69 percent of whom are part-time. Is it not the same in government? The moment we ask for formality we are told that formality is out of date.

The next director of the National Park Service will bring back the teachers, along with the formality of what it means to teach. Get rid of the uniform and wear "comfortable" clothes? No, get rid of the attitude that service to the public is ever comfortable. And yes, service begins by answering your mail.