Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark contains many hazardous wastes/NPS file

Editor's note: Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark has not been placed on the National Priorities List as a Superfund site by the Environmental Protection Agency. However, the National Park Service has identified significant toxic and hazardous wastes there and is going through the process of conducting studies to determine the "nature and extent of contamination and assess whether the contamination presents a significant risk to human health or the environment." In 2015 the Park Service conducted a "preliminary assessment" of the mine site to determine the extent of contamination. Based on the findings, the agency moved forward to perform a Remedial Investigation/Feasibility Study, which falls under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, commonly known as Superfund. As stated by the EPA, CERCLA authorizes two kinds of response actions:

- Short-term removals, where actions may be taken to address releases or threatened releases requiring prompt response.

- Long-term remedial response actions, that permanently and significantly reduce the dangers associated with releases or threats of releases of hazardous substances that are serious, but not immediately life threatening. These actions can be conducted only at sites listed on EPA's National Priorities List.

As the Park Service notes on the Kennecott Mines website, "At the Kennecott Mines and Mill Town Site, cleanup phases and milestones are based on CERCLA and its implementing regulations documented in the National Contingency Plan (NCP). The NCP establishes the structure for responding to releases and threatened releases of hazardous substances.

Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark: A Toxic Site

By Barbara 'Bo' Jensen

I’m the last person at the end of the historic Kennecott Mill tour, standing just outside the door of the final room we walked through, a space filled with towering ammonia tanks. The tall, cylindrical, industrial vats, with their steampunk rivets and old-fashioned hand cranks, now sit silently rusting, stained all around from leaked copper and ammonia, iridescent colors emerging in the filtered sunlight streaming through the mill’s high windows.

The 14-story copper mill is part of the Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark located within Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve in south-central Alaska. These high mountain mining towns, independent McCarthy and company town Kennecott (misspelled at its inception), provide breathtaking views, looking out from these precipitous slopes across vast terminal moraines of the Kennicott and Root glaciers that feed the Kennicott and Nizina rivers.

I wait, blinking in the sunlight, for the tour guide to exit the rickety wooden building, its floors stair-stepping irregularly down the side of the steep mountain. Floor by floor, he had led us across catwalks, through narrow stairways, and down vertical ladders, descending through the concentration mill like the copper ore itself, past gigantic gears and heavy beams, dusty rocker tables and oily work benches, and always more ore chutes dropping away into darkness.

As he appears, rattling his keys and working the door lock, I step over to wrap up our conversation, confirming, “And this whole place, it’s a toxic Superfund site, isn’t that right?”

He glances at the other tourists who are already leaving the area, chattering as they walk off into the partially restored mill town and the beautiful Alaska late-summer day. He clicks the lock. Then he turns back to me.

“That’s correct.” He nods, his expression serious. This fact has not been stated at any point during the two-hour tour…as if maybe he’s not supposed to bring it up. He seems relieved that I know.

Don’t worry, I think to myself. The Park Service has a plan.

There are handwashing stations available to park visitors/NPS file

To be specific, it’s a Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act remediation plan; also known as CERCLA/Superfund, federal legislation from 1980. That’s right: Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve has an Environmental Protection Agency-mandated cleanup plan for the kind of environmental contamination I typically associate with notorious places like White Sands, the atomic bomb testing site in New Mexico — which is also now a national park.

How did the National Park Service become stewards of Superfund sites?

The answer seems tied to the agency's mission to preserve places of historic and cultural value. In fact, the National Park Service has a specific team dedicated to monitoring and enforcing CERCLA provisions on the lands it manages: the NPS Environmental Compliance and Cleanup Division (ECCD). The ECCD website notes: “The National Park Service Contaminated Site Inventory consists of more than 500 legacy pollution sites, representing approximately $1.5 billion in total cleanup costs.”

As of August 2023, more than 70 percent of national parks are contaminated with legacy pollution of some type. ECCD’s role is to ensure these sites are made safe for visitors — and for park staff, including NPS-contracted concessionaires like the concerned tour guide. And ECCD does not have $1.5 billion.

At the Kennecott site, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve illustrates the essence of America’s recurring, contradictory approach to its abundant resources — boom and bust. Riches found, taken and used up, and the detritus of our excess casually left behind like litter on the roadside.

On one hand, Wrangell-St. Elias boasts the kind of rich superlatives one might expect from Alaska, America’s fabled, fantastic last frontier:

- Largest national park in the United States: 13.2 million acres, the size of six Yellowstones;

- Largest wilderness area in the National Wilderness Preservation System: 9.6 million acres;

- Four major mountain ranges: the Wrangell, St. Elias, and Chugach Mountains, and part of the Alaskan Range;

- Second highest peak in the United States: Mt. St. Elias, at 18,008 feet (5.5km);

- One of the largest active volcanoes in North America: Mt. Wrangell, at 14,163 feet (4.3km);

- Over half of the 16 highest peaks in the United States.

Located on the Canadian border, Wrangell-St. Elias — together with Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve, Kluane National Park and Reserve, and Tatshenshini-Alsek Provincial Park (the last two in Canada) — is designated as a World Heritage Site, the world's largest international protected wilderness. This is a bountiful, untamed, and powerful place that demands respect, even awe and reverence, and, in terms of survival, utmost preparation and caution.

But on the other hand, Americans aren’t known for a history of caution, or respect, especially when a wealth of lucrative resources shines from the mountaintops like a beacon. That’s why Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark is also a story of valorizing greed and exploitation.

Some areas of the site are fenced off because of toxic and potentially explosive materials/NPS file

Hard To Reach

It’s a long road to the Kennecott Mines. After Chitina, a sign at the entrance to the four-wheel-drive McCarthy Road emphasizes checking locally for road conditions and services beyond this point:

- Road ends at Kennicott River – 62 miles

- Limited Vehicle Services

- Drive at your own risk

- Watch out for loose railroad spikes

That last warning is because the road follows the old Copper River & Northwestern Railway, or CRNW, referred to by track workers as the “Can’t Run and Never Will” during its 1907-1911 construction through nearly impassible terrain. The line was built by the Kennecott Mines Company specifically to haul copper ore from Kennecott Mill to the port of Cordova, Alaska, 200 miles away.

The Native Alaskan Ahtna people live here; historically, they worked this area’s copper to make tools. Russian fur traders had contentious relationships with the Ahtna, so when Russia sold Alaska to the United States in 1867, neither country knew of the motherlode. In the 1880s, the U.S. sent military expeditions to explore the Alaska Territory. The soldiers heard the Ahtna’s rich cultural stories, which included their source of copper — and others heard them, too. Soon, prospectors Clarence Warner and “Tarantula Jack” Smith followed copper ore up a creek to its source, and on July 4, 1900, they staked a claim on the Bonanza Mine. The ore assayed at 70 percent chalcocite, one of the richest copper deposits ever found.

Chaos ensued.

1n 1900, copper was in high demand worldwide, for industrial heating and cooling pipes, for electricity and communications wire, and for munitions. The prospectors fought multiple competitors for their claim in the territorial and federal courts. They ultimately lost the site that would become Kennecott Mines in a hostile takeover by mining engineer Stephen Birch — representing powerful American industrial magnates Guggenheim, Morgan, and Havemeyer. They became the “Alaska Syndicate,” controlling the Kennecott Mines Company. As the new managing director, Birch quickly hired more than 500 men to begin mining, even as another 500 men had only just begun constructing the railroad line.

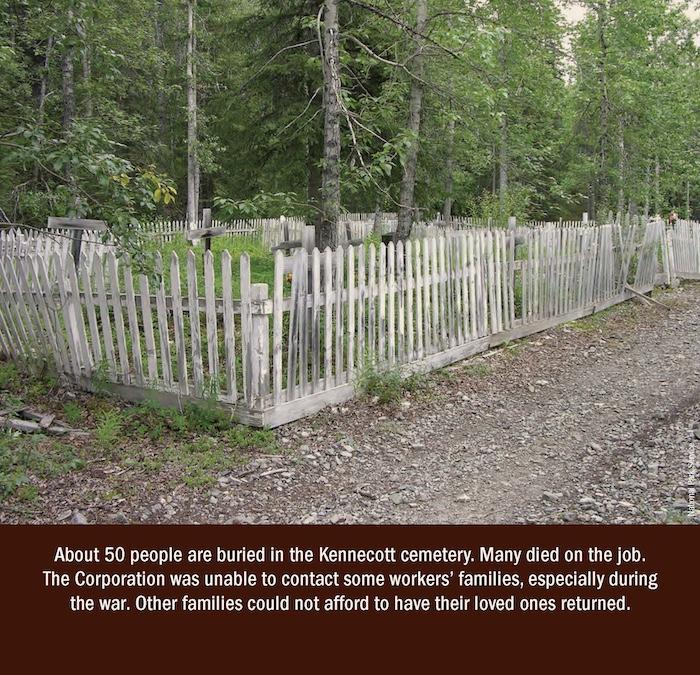

A company town sprang up seemingly overnight. Much has been made of cozy reminiscences recorded from the “Kennecott Kids,” children of Kennecott managers and community professionals from the 1910s and 1920s. They tell stories of Christmas parties, dances, and community picnics. But the workers’ housing was not set up for families; most miners and mill workers could not bring their wives and children.

Mine workers moved up to 1,200 tons of ore per day, living at the mines in on-site bunkhouses, with two days off a year, Christmas and Independence Day. Miners were required to sign a liability waiver because they rode the ore buckets on cables between mines and from the mines to the mill, and the turn stations at the end of the line easily mangled a man’s head or arm if he wasn’t attentive. Temperatures plummeted in winter, often -40 to -60 degrees Fahrenheit at night.

The mill was also dangerous, and noisy. Heavy ore arrived from the mines “every 52 seconds” per one worker’s account, and was pushed by hand through the massive metal “grizzly grates” to begin separation. Turnbuckles helped stabilize the building to stop it from shaking itself apart as the ore poured down the wooden chutes. Dust hung in the air everywhere, and fire was a constant concern. Huge canvas drive belts, configured in a twist to self-balance and open to passing workers, ran at 450-550 rpm continuously. The mill supervisor reportedly kept a large backstock of ore on hand so that no matter the day’s mining productivity, the mill would keep running 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. The racket could be heard in McCarthy, five miles away. Between the mines and the mill, there was high employee turnover.

In 1917, the workers went on strike.

It didn’t last long.

Kennecott was visibly segregated, with “important” buildings — such as the hospital, and management homes, like Birch’s — set on higher elevations and painted white. Ordinary workers lived and worked in lower-placed, red-painted buildings — the mill, the mill dormitory, the company store. Exploitation, a key to the mine’s financial success, was clearly coded into the entire operation. It was typical of early 20th century American industry.

Birch was known to hold strong anti-union sentiments. In exchange for the names of the strike organizers, he raised worker pay. World War I had begun; the Alaska Syndicate was making more money than ever and could easily afford the small increase. He then fired the strike organizers. And a few months later, at the end of their contracts, he fired all the strikers, too.

By 1938, the Kennecott Mines Company shut down operations. Their geologist had advised that the final bust had come. The Great Depression had hit the company hard, as copper deposits were running out. Finding cleanup in the remote area to be cost-prohibitive, the company sold off what equipment it could and left the rest in place, in case advances in technology made mining profitable again in the future.

Kennecott Mines received its National Historic Landmark designation for the ammonia leaching process developed and used here, untested, for the first time. Mine tailings were poured directly into the tanks I had seen, to soak in those vats of ammonia. When evaporated off, the process allowed for 90 percent recovery of mined copper. Subsequent improvements raised that rate to 98 percent. Kennecott Mines incidentally recovered 291 tons of silver — so much that the silver paid for the entire process. The operation processed more than $200,000,000 worth of copper ore by 1938; in today’s dollars, that’s the equivalent of the Alaska Syndicate making roughly $4 billion on Kennecott Mines copper.

Careful Where You Go

I didn’t go up to the mines. Bright gold National Park Service warning signs throughout Kennicott proclaimed:

NO PASSING BEYOND THIS BARRICADE — CAUTION

Heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, mercury, copper, zinc, chromium, cadmium, and barium are consistently present in elevated quantities in the mine tailings and soil as well as other places throughout the mill site. These are harmful to your health and especially to children under the age of six and pregnant women.

Follow these simple healthy actions to reduce your contact with the hazardous gravel and dust:

Stay on established roads and trails.

Avoid skin contact with the ground, artifacts, buildings, wood remnants, and tailings (small blue, green, or gray gravel-like rocks) that may contain hazardous heavy metals.

Wash hands before eating or putting anything in your mouth.

When you get home, wash your shoes.

Wipe off your pet’s dirty paws, too.

Wash harvested berries before eating.

Wrangell-St. Elias’ Kennecott Environmental Investigation Project under CERCLA states that in 2019, “NPS conducted an exposure assessment to evaluate potential airborne contamination and fugitive dust exposures to park employees and park visitors. Based upon the results of that investigation, air quality at locations inside and outside of buildings throughout the Mill Town is considered safe and not expected to present a hazard to visitors or park workers.”

Layers of dust coat the machinery that's been silent for decades/Barbara Jensen

The air is safe. But what about the dirt roads, the wooden structures, the heavy metals, the caution signs, the site itself? This park has installed outdoor public handwashing stations, a move that raises more concerns than it eases.

Inside the mill, I had noticed how the tour guide avoided contact with any surfaces. He had advised the group several times, “I don’t recommend touching anything due to contaminants.”

“Like what?” I had asked.

“A lot of nasty stuff” was all he would say.

I’m not sure what historic and cultural values the National Park Service is caring for here: a landmark to our toxic industrial processes? To the greed of American tycoons? Their legacy of exploiting resources and leaving Superfund sites in their wake?

By 1974, the reformed Kennecott Copper Corporation was the world's largest independent copper producer. It is now part of international mining giant Rio Tinto, whose 2022 revenues exceeded $55 billion.

We are paying to clean up this mess with our hard-earned tax dollars. Those miners who went on strike must be rolling in their graves.

Barbara 'Bo' Jensen is a writer and artist who likes to go off-grid, whether it's backpacking through national parks, trekking up the Continental Divide Trail, or following the Camino Norte across Spain. For over 20 years, social work has paid the bills, allowing them to meet and talk with people living homeless in the streets of America. You can find more of Bo's work on Out There podcast, Wanderlust, Journey, Deep Wild, and www.wanderinglightning.com

Kennecott Mill Town/NPS, Bryan Petrtyl

Comments

Nice story.

Just so you know, you received VERY incorrect information on your tour. Kennecott is NOT a designated superfind site. The entire premise of this article is wrong. I have lived and worked in this area for over 20 years. A very quick search on this official EPA site confirms that there is no superfund site in the Wrangell-St. Elias region. You and your tour guide are probably going to get quite a bit of flak for this.

https://www.epa.gov/superfund/search-superfund-sites-where-you-live

Kennecott Mines and Mill Town Site has a full CERCLA cleanup plan: (https://www.nps.gov/wrst/learn/management/kennecott-mines-and-mill-town-...) The CERCLA hotlink on that page can give you some more background on CERCLA/Superfund.

The plan you link to shows that there is an *assessment* taking place to determine whether or not the site is in fact qualifying of CERCLA cleanup funds. In the meantime NPS is authorized to mitigate acute hazards should they be discovered. This is MUCH different than Kennecott being a "toxic superfund site," which again, it is NOT. There is NOT a "CERCLA cleanup plan" in place for Kennecott at this time. Please at least acknowledge that Kennecott does NOT appear on the EPA list of designated superfind sites.

"four-wheel-drive McCarthy Road" isn't quite correct. It's easily driven in almost any vehicle these days.

The location is NOT in Southeast Alaska. It's in SouthCentral Alaska~ Southeast would put it down on the Panhandle. I've vistited the area many times, and am a 40 year Alaskan who knows this area well.

Thanks for the catch. Fixed.